From Alaska to Maine, fishermen set thousands of traps and pots every day. Not all of them come back. Lines part, buoys are destroyed by passing boats and tides and storms carry traps into deeper water. These are the infamous ghost traps that, in some cases, continue to fish for years.

There’s been a lot of effort to remove derelict traps, but last year NOAA launched four gear innovation projects to not only attempt to better understand the problem but to prevent traps from being lost in the first place. The projects received Fishing for Energy gear innovation grants administered by the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation and funded by NOAA’s Marine Debris Program.

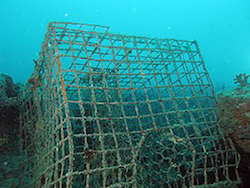

A derelict fishing pot sits on the bottom of the South Atlantic. NOAA photo

The projects are taking place in Washington’s Puget Sound, South Carolina’s Stono River and in Maryland and Virginia’s respective portions of Chesapeake Bay.

Crab mortality caused by ghost fishing is a significant problem in Puget Sound. It’s estimated that 30,000 crabs are killed each year in derelict pots, even though they have cotton panels designed to disintegrate and let crabs leave the pots. The problem is the pots’ design limits a crab’s ability to escape, even when the cotton panel is gone.

A project run by the Northwest Straits Foundation is testing several crab pot designs for their escapement rates to determine the most efficient pots. Recommendations will include trap modifications to improve escapement rates.

Some of the results will be released in the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife’s annual Fishing Pamphlet that informs fishermen of new rules and regulations.

In Maryland’s portion of Chesapeake Bay, NOAA ran a side-scan sonar survey in 2007 and estimated there were 84,567 derelict crab pots. After some initial work on technologies to reduce ghost fishing, it’s being suggested that commercial blue-crab fishermen might use side-scan sonar to improve the pot-retrieval rate.

In South Carolina, traps are lost when passing boats destroy floats on the surface or cut the trap lines. Researchers are comparing the standard single float and line to using PVC piping to protect the line and testing floats to find one made out of material that’s more durable.

What’s different about the South Carolina project is how the recovered crab traps will be recycled. They’ll be cement coated and then dumped back into the water to create oyster reef habitat. The cement provides a settlement substrate for oysters.

In Virginia, the Virginia Institute of Marine Science is testing biodegradable escape panels and visual deterrents on peeler crab pots. Thirty peeler pots were given biodegradable escape panels that were tested against 30 standard peeler pots. Preliminary results suggest no adverse effect from the biodegradable panels on the catch rate.

There are also indications that the color of the entrance funnel can deter turtles from entering a trap while enhancing blue crab catch rate.