Day 10 — Hearing conclusion

The U.S. Coast Guard and National Transportation Safety Board officially concluded the two-week public hearing into the sinking of the Bering Sea crab boat Scandies Rose on Friday, March 5.

The joint investigation board reviewed and considered evidence related to the loss of the vessel and five of the seven crew, which occurred on Dec. 31, 2019.

Coast Guard Cmdr. Baxter Smoak walked the hearing through the official process of marine investigations.

Annually, the Coast Guard performs about 19,000 preliminary investigations on marine incidents. Of those, 3,500 become reportable marine casualties, which can fall into one or more of four categories — routine incident, serious marine incident, significant marine casualty or major marine casualty. Most of those 3,500 do not result in a formal hearing. — Jessica Hathaway

Day 9 — Crabbing safer but with room for improvement

A presentation about marine safety in the Alaska fishing industry during day nine of the Scandies Rose inquiry put the vessel’s tragedy in recent historical context, showing an industry that has made strides but still has room for improvement.

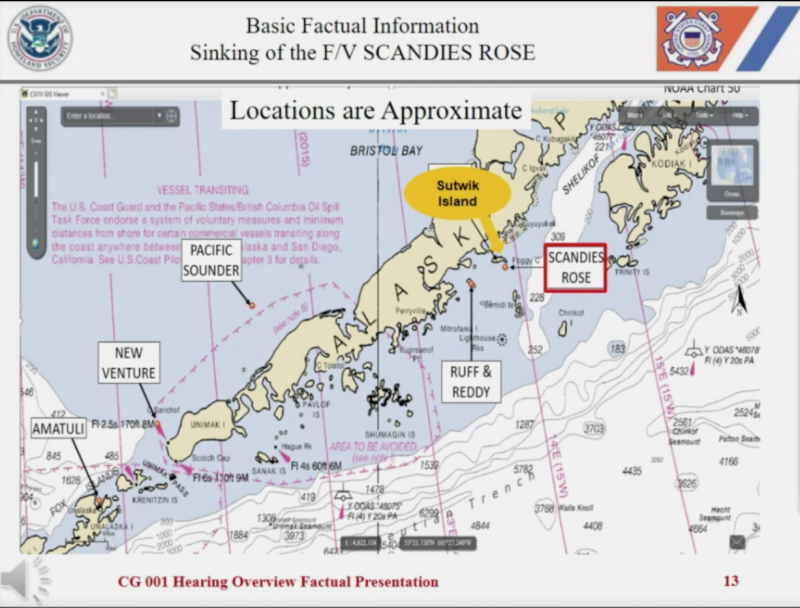

At the beginning of her report on Thursday, Mar. 4, Dr. Jennifer Lincoln, a marine safety expert for the National Institute of Occupational Safety, flashed a montage of newspaper headlines from the 1990s. It is a heartbreaking string of notifications of one Bering Sea/Aleutian Islands crab boat down after another: Pacific Apollo, Barbarossa, Harvey G, Saint George, Massacre Bay, Nettie H, Northwest Mariner, Pacesetter, Lin J.

“This type of headline where the Coast Guard was investigating a boat vanishing was unfortunately very common,” Lincoln said.

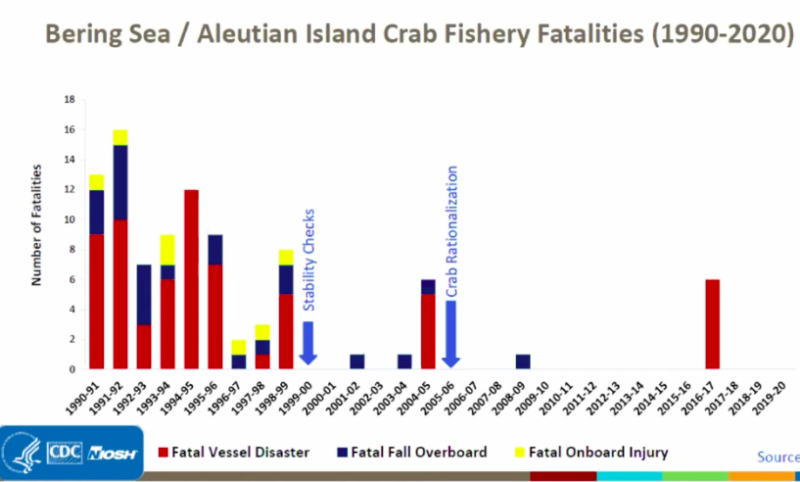

NIOSH tallies 72 deaths in the BSAI crab fishery from 1990 to 1999, the majority from vessel disaster.

“The patterns that were emerging were that these capsizings were occurring usually the first day of the opilio fishery when the vessels were fully loaded, and the investigations that the Coast Guard went through found that many of the vessels were overloaded,” Lincoln said.

These tragedies would mobilize the industry to reduce fatalities by 69 percent from 1990 to 2019. According to Lincoln, increased safety was helped along by new legislated regulations, increased Coast Guard presence in the area, and an improved culture of safety among fishermen.

But the most drastic drops in the fatalities come after two developments in particular: stability checks at docks and later fishery rationalization. After stability checks were implemented in October 1999, fatalities dropped from eight deaths a year in the 1990s to eight deaths over the next five years. Then in 2005, managers rationalized the fishery, giving each boat a set quota instead of a derby-style fishery. NIOSH reports just one death in BSAI crab from 2005 up until the sinking of the Destination in 2017.

Rationalization, Lincoln explained, consolidates the fleet, typically weeding out smaller boats more prone to capsizing. It also slows fishing down and lengthens the season by increasing fishing days, which in turn reduces fatigue and gives skippers the option to sit out bad weather.

However, Lincoln said the transition from a derby to a quota fishery can have unintended consequences, consequences that may have factored heavily into decisions before the Scandies Rose’s final trip.

“There is evidence that shows there is a race for catch history that occurs prior to a fishery being converted into a quota based management system,” Lincoln said.

The Scandies Rose was on its way to fish a short pod cod season — still a derby fishery — before switching over to opilio crab. Survivor Dean Gribble testified that he felt Scandies’ skipper Gary Cobban Jr. had rushed out into inclement weather to build pot cod catch history in anticipation of its pending rationalization.

During testimony later in the day Thursday, Scandies Rose majority owner Dan Mattsen denied that building cod catch was part of their fishing plan but acknowledged that Cobban Jr. had autonomy of his own vessel.

“Gary was a 30 percent owner of the boat. Gary had much more experience than I did as a captain. Although I’ve been in the industry for 40 years, Gary was a frontline captain from the time he was just a teenager, so I would never second-guess Gary’s decision making. I would just trust that he would do the best for himself, for the boat, and for the crew,” Mattsen said.

Mattsen’s afternoon testimony, the second time he has sat before the Coast Guard Marine Board of Investigation during the hearing, came after testimony from Bruce Culver, a naval architect who did a stability report on the Scandies Rose in April 2019.

A review of Culver’s stability report by a naval architect from the Coast Guard’s Marine Safety Center found it contained “significant errors and omissions,” in particular in regards to stability criteria and downflooding points.

Culver, who said he has provided more than 200 stability reports in his 30-year career, defended his work, and Mattsen refused to blame him.

“It’s for other engineers to judge the quality of the work. I’m not throwing Mr. Culver under the bus. I’m a fisherman,” Mattsen said.

Culver passed off some of the perceived deficiencies in his stability report as things that Cobban would already know as the skipper of the vessel, and Mattsen seemed to agree, saying that captains typically have an intuitive sense of the stability of their boats and can tell when icing reaches a critical level.

Mattsen spoke at length about his relationship with Cobban, explaining they were often at odds about how to go about the business of fishing.

“Gary and I weren’t buddies. I miss him because he was a great captain and a great fisherman, but we weren’t like buddy-buddy… I pay attention to the bottom line and recognize there are financial limits to what you can do, and Gary didn’t recognize those limits. He wanted the world,” Mattsen said.

Mattsen admitted a weld job by Aztec Welding on a fore bycatch chute was a “cluster,” and said there should have been non-destructive testing on the weld. He recalled receiving a late bill for the job from Aztec with what he perceived to be inflated hours and seemingly made-up names for welders, including Ratatoiulle, Colorado, Spain and Ardilla. The weld job was redone in Kodiak prior to Scandies’ final voyage and has been a focus of the investigation as a possible source of downflooding.

In his closing comments, Mattsen did question Cobban’s decision to have newcomers Gribble and Jon Lawler, the sole survivors of the accident, take back-to-back wheel watches on the night of the accident, but he did not blame Cobban for the accident.

“Gary was a very good captain, and he was doing his best to get the boat to a safe place. You can say probably there were some mistakes, having two people who weren’t familiar with the vessel back-to-back on the watch at that time was probably not the best practice… He probably just didn’t have enough time to process everything that was coming at him. He had a lot of faith in his boat. He’d been through a lot with it and knew that it was a good ride,” Mattsen said. — Brian Hagenbuch

Day 8 – Safety expert: Train with your raft, carry flashlights, PLBs

Scandies Rose survivors Jon Lawler and Dean Gribble had a flashlight in the life raft and used it to attract attention of the Coast Guard aircrew that rescued them. Safety expert Mario Vittone – a former longtime Coast Guard rescue swimmer himself – testified how that’s one lesson from the accident.

“A waving flashlight will turn an aircraft,” and flashlights run for hours compared to flares that burn for 30 seconds, Vittone told the Coast Guard marine board of inquiry looking into the Dec. 31, 2019 sinking and loss of five fishermen. “I would trade every flare on my boat for three waterproof flashlights.”

With 22 years of service in the Coast Guard and Navy, Vittone is general manager of Lifesaving Systems Corp. in Florida. In his interview with the board he talked about the realities he’s learned about life rafts, survival suits and other essential emergency gear.

Vittone remembered his reaction when Coast Guard and National Transportation Safety Board reports on the 2015 El Faro disaster – the loss of a U.S. flag cargo ship and 33 lives – included a recommendation that personal locator beacons be required.

“When I read those two lines…I stood up and shouted, ‘Yes, finally!’” he said. “There is no piece of gear out there that will reduce the time to rescue like a personal locator beacon.

“It is the greatest advance in maritime safety in the past 100 years,” said Vittone. “It tells the (Coast Guard) Rescue Coordination Center exactly where that person is.”

Floating emergency position indicating radio beacon (EPIRB) devices carried on vessels will lead rescuers to the site of a sinking. PLBs only work if affixed to a survival suit or vest worn by survivors floating in the water, so aircrews can track directly to them.

In their testimony, survivors Gribble and Lawler described struggling to get into one of the Scandies Rose life rafts that inflated automatically after the sinking. With the raft itself almost full of water, they scrambled about inside to keep it stable, and searched blindly in the freezing water for survival gear.

That’s not uncommon, even without 30-foot seas, said Vittone.

“Training with a raft is one thing, but it’s better to train with your raft,” said Vittone. Fishermen can do it as part of the annual raft servicing – opening it up and getting familiar with how it works and is laid out, he said.

“There’s signage (instructing how to use the raft and gear) and you’re not going to be reading those in the dark,” he said. Rafts are cramped – a raft rated for six persons barely holds that many – and getting aboard them is physically difficult, he said.

Some manufacturers now have rigid boarding platforms as steps to get into their rafts. But “if the platform folds under one or two people, it’s not adequate,” said Vittone.

After the October 2012 sinking of the replica square rigger HMS Bounty off North Carolina in Hurricane Sandy, survivors struggled for 30 minutes to get into a raft, some resigned to just hanging on, Vittone recalled.

“Someone finally got mad enough to get in and pull the rest of them in,” he said.

The Scandies Rose survivors testified how their crew struggled to get into survival suits as the rapidly destabilized boat tilted under them. Vittone told how it is critical that fishermen have the right-sized suits at hand.

“The biggest danger is the suit doesn’t fit,” said Vittone. Fishermen must compare and try on sizes and beware of one-size-fits-all tags, he said.

The design of immersion suits provides flotation and warmth, so that any water that gets zipped up inside with the wearer is warmed up by body temperature.

But “if you’re wearing a too-large immersion suit, it can kill you” with cold seawater continually leaking in, he said. “They’re not one-size-fits-all, despite the universal label.”

Keith Fowler of the Coast Guard’s marine casualty investigations center questioned Vittone about the difficulty of using radio controls while wearing a survival suit. Vittone said suits with gloved hands may allow some dexterity compared to mitten-style suits.

But he said keeping one hand free of a suit is dangerous in the extreme cold the Scandies Rose crew faced, when the water temperature was a reported 39 degrees Fahrenheit.

It’s better to send the mayday call, punch out a digital selective calling distress signal, activate the EPIRB and zip into the suit, said Vittone.

“If there’s time to do that,” he added. “If the boat is upside down, I’m getting in my suit and jumping off, and hoping someone else did it.”

Once in a raft, survivors without a handheld VHF radio have little to do but wait and hope. But in extreme weather they may not even hear an approaching aircraft.

Vittone recalled one case when the Coast Guard located a raft 250 miles offshore in the Atlantic, in 30-foot seas, and a helicopter crew dropped their rescue swimmer.

The survivors never heard the aircraft hovering overhead, he said: “He jumps into the raft and frightens all three of them.”

The best scenario for evacuating a sinking is for fishermen to take their EPIRB with them, said Vittone. The devices are design to float free and transmit automatically, but they will drift apart from survivors at different rates, widening the search area when rescuers arrive, he said.

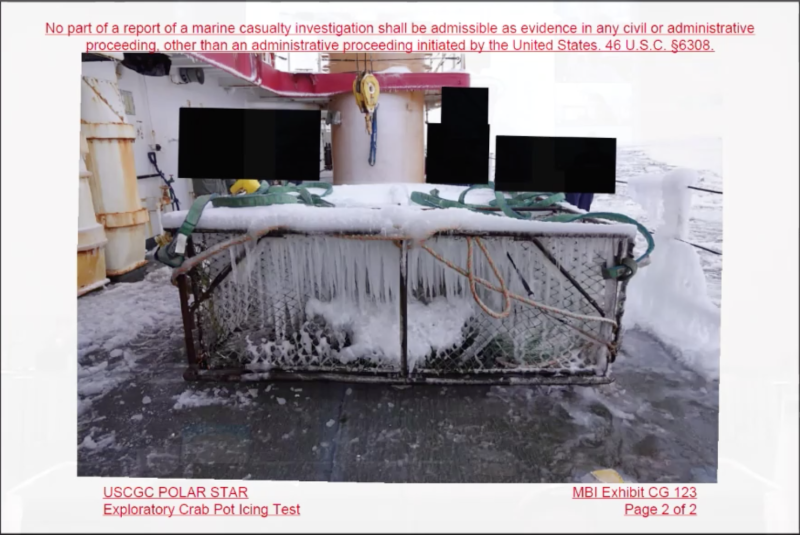

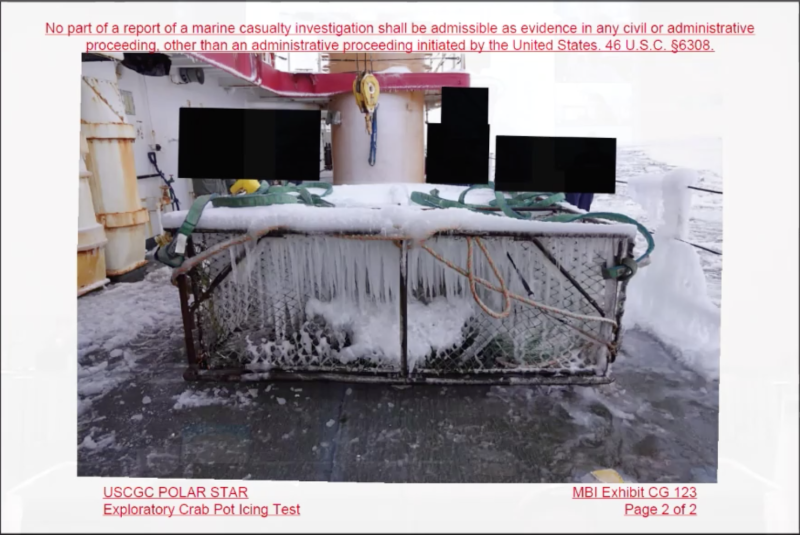

The board of inquiry is probing the role of icing in the Scandies Rose case, and whether current safety standards and guidelines are sufficient. Jaideep Sirkar, chief of the Coast Guard’s naval architecture division, testified Wednesday.

Testing in Alaska has shown icing can increase the weight of a single crab pot to more than 3,000 pounds. Adding that kind of weight puts a vessel deeper in the water, and raises its center of gravity, making it less stable, said Sirkar.

Windblown freezing water creates asymmetric icing – more on one side of a vessel – that can lead to a persistent list. That creates a risk of downflooding through openings on the lower side of the vessel, said Sirkar.

Heavy icing was cited as a factor in the February 2017 sinking of the crab boat Destination with the loss of six crew members. When findings from that investigation were issued in March 2019, Coast Guard leaders said existing regulations should have prevented the loss and blamed the vessel owner and captain for failing to follow them.

“There was no regulatory action” as a result of the Destination inquiry, Sirkar told Cmdr. Karen Denny of the board.

Recommendations from the Destination investigators included additional language in regulations dealing with icing on pots and open deck gear, said Sirkar. While those regulations have not been amended, Sirkar said his office continues to put out alerts to industry warning of icing hazards. – Kirk Moore

Day 7 — An improbable rescue on a violent winter night

Day seven of the Scandies Rose inquiry took a closer look at the harrowing incident from the rescuers’ perspective, with especially vivid testimony from one of the Coast Guard pilots who flew the helicopter that plucked survivors Jon Lawler and Dean Gribble from the ocean early on New Year’s Day 2020.

Conditions were bad enough onshore that Coast Guard helicopter pilot Chris Clark said he drove to the hangar in Kodiak with his head out of the window of his truck so he could see. When Clark and his team got clearance to fly toward the last known location of the Scandies Rose — about 190 miles southwest of Kodiak — they encountered even more violent conditions.

“We were anticipating bad weather, but it ended up being a lot worse than what we thought,” Clark said.

A Coast Guard case review would later quantify Clark’s “bad weather” — seas 20 to 30 feet, winds 35 to 50 knots, heavy snow, and air temperatures down to 10 degrees F.

“We weigh risk versus gain. We knew going into this that it was going to be a very high risk mission. Weather. We were flying into the middle of the night… Obviously the gain was high as well, which is why we ended up taking off and completing this mission,” Clark said.

By the time the Coast Guard helicopter crew left Kodiak, it had been four hours since Captain Gary Cobban Jr.’s scratchy mayday call that announced the Scandies Rose was rolling over. Time was critical, and the relatively long distance and stiff headwinds meant fuel in the MH-60 Jayhawk would limit their search time. The team decided to take the most direct path to the accident site, a route that sent them down Shelikof Strait, a funnel notorious for amplifying winter weather.

“I think this was the most challenging flight of my career, just getting out there. We were hitting multiple downdrafts and such turbulent air that it basically took both pilots to keep the aircraft flying,” Clark said.

Once in the strait, Clark said the ceiling was down to 300 feet and that visibility ranged between half a mile to “not much at all,” forcing he and co-pilot Jonathan Ardan to rely largely on instruments for guidance.

“All that snow coming in gives it that Star Wars effect, which is very disorienting as a pilot. Most of the night we were inside on instruments, hawking the altitude and airspeed. We also had our radar, which kind of gives us a good idea about what’s ahead of us and where we are,” he said.

The four-person crew was rounded out by mechanic Jacob Dillon and rescue swimmer Evan Grills, a Florida native who was 24 years old at the time and on his first live rescue mission in Alaska water. En route, the crew discussed how they might go about hoisting survivors in such adverse conditions.

When they finally got on scene, an unexpected stroke of luck greeted them.

“The weather miraculously opened to about two miles. We were under night vision goggles the entire time, and that’s probably the way we spotted the raft, which looked like a flashing light going up and down,” Clark said.

They flew toward the light and were able to positively identify it as a raft, but were faced with a difficult panorama. Buffeted by slashing gusts and hovering at a maximum of 60 feet off the water, the helicopter’s altimeter registered swings of 30 feet, indicating the size of the seas heaving below. The water temperature was later reported at 39 degrees. The crew decided to keep Grills on the hook.

“We sent the rescue swimmer down and he was able to signal up to indicate there was no one in the raft. Everyone was a little deflated at that point,” Clark said.

It was likely around this time that Lawler and Gribble heard the helicopter above, a sound Lawler would later describe as the best thing he had ever heard. As they were hoisting Grills back into the helicopter, Ardan spotted another light under his night-vision goggles.

“It was not a normal blinking light. It was side to side, so we knew it was somebody trying to signal us,” Clark said.

They got Grills back in the helicopter and, as the pilots hovered toward the new lights, Dillon knocked the ice off the Floridian.

“It was so cold that the rescue swimmer, just from going out the door and coming back up, was covered in ice. They had to chip the ice off of him, brush it off, and clear his mask so he could see,” Clark said.

A newly deiced Grills went down again as the pilots struggled to keep the plane over the raft where Lawler and Gribble improbably persisted. Grills was able to strap in one survivor. But up in the helicopter, cold had stripped Dillon’s fingers of feeling and dexterity. Clark ran the hoist hook and got the first survivor on, and they again knocked the ice off Grills and sent him back down.

“Once we got them in the helicopter, I wanted to get information on where the rest of the crew was. The flight mechanic was able to talk them. I got the word that they were the only ones who had got their survival suits on and made it off the ship,” Clark said.

Fuel burning quickly, Clark made the decision to ride the stiff tailwind back into Kodiak. To save fuel, they turned the heaters off in the helicopter, which Clark said made for a frigid 40-minute ride back into town.

“I was freezing up front, and it’s much colder in the back. The flight mechanic made a comment about how he was slipping on the deck when we were pulling the survivors in because of the ice on the deck of the helicopter,” Clark said. — Brian Hagenbuch

Day 6 – Scandies Rose survivor Dean Gribble recalled crew’s unease over weather, pressure to start cod season

The crew of the Scandies Rose was apprehensive about impending weather as they departed Kodiak, under pressure to get to the Bering Sea cod grounds soon, survivor Dean Gribble testified to the Coast Guard marine board of inquiry into the Dec. 31, 2019, sinking.

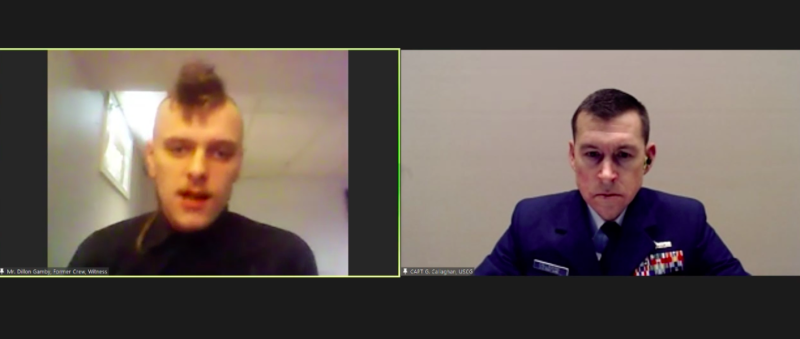

“We just shouldn’t have left into a storm. That was a bad call,” Gribble said in a wide-ranging, often emotional interview with Coast Guard and National Transportation Safety Board investigators. Recorded Sept. 23, 2020, the video was entered into the record Monday, when board chairman Capt. Greg Callaghan said he had determined that there was no need to recall Gribble for live testimony before the panel sitting in Edmonds, Wash.

“We were all talking about it,” Gribble continued. “We were all like, 'Oh boy, this is going to be fun.'” The men looked at the Windy weather app on their smartphones, and the color display layer showing forecasted low pressure.

“The darker it is, the worse it is going to be. It was like maroon, or dark purple,” said Gribble.

But captain Gary Cobban Jr. wanted to get out to the Bering Sea pot cod fishery, in anticipation that January 2020 could be the last season of a derby-style fishery, before an individual fishing quota management system, said Gribble. Those final days of the old fishery would be critical to establish vessel catch history, and in turn their future IFQ share, he said.

“We were already a day or two late, so it was really important for us to get to the grounds,” he said.

Preparing in Kodiak, “all the rows of pot had chains. We put a belly chain around, just making everything tight because we knew the weather was going to be bad,” Gribble recalled.

On New Year’s Eve Gribble started his night watch at 7:15 p.m., and soon the weather was deteriorating, beating harder with quartering seas and icing. He noticed a slight change in the boat’s ride.

“We started to list a little bit to the starboard side,” he said. “It felt like it was little heavier.” The previous watch had not mentioned this to Gribble, so he told Cobban about it when the captain came up to the wheelhouse.

“He didn’t seem concerned,” said Gribble. With some icing on the wheelhouse and glaze on the pots, he asked Cobban if he wanted the crew to break ice, and the captain replied they could do that later at False Pass, about 100 miles ahead, said Gribble.

Relieved from the watch, Gribble said he went below to make a sandwich and go to the stateroom he shared with crewman Jon Lawler. About 9:30 p.m., “I felt the boat go hard starboard. My first instinct was we were turning to run with it, to give us a break from the ice, a little safer ride,” said Gribble.

In the lower bunk, Lawler jumped up and went upstairs to see what was happening. “Deano, the boat’s sinking!” he shouted down.

Gribble scrambled into clothes and bolted up to the wheelhouse. Cobban was leaning on the chart table against the increasing starboard list as Lawler started pulling survival suits out of a locker, said Gribble.

“What’s going on Gary?” he shouted.

“I don’t know,” the captain said. Gribble told him to radio the Coast Guard, “Tell ’em we’re sinking.” They rousted the rest of the crew to get into the survival suits and get outside.

The boat already felt to be “in a free-fall” as the crewman struggled on the tilting deck to get into the suits, said Gribble. He yelled at crewman David Cobban, the captain’s son, to grab extra flares out of a locker.

“He was just sitting there, with his suit fully on, just sitting there in shock,” said Gribble.

Then at the engine controls, Gary Cobban “took it out of gear,” said Gribble. “As soon as he took it out of gear, everything sped up.” The vessel lights went out, and in pitch darkness he struggled to help Lawler pull his suit’s zipper up.

Feeling the boat rolling farther, Gribble and Lawler reached for a life ring, hoping to stay together in the water using the line. They inched past the house, yelling at David Cobban to follow them, said Gribble.

They tried to climb higher on a tilting house, holding the line so it would not get snagged, said Gribble. He told Lawler, “as soon as that line is clear, we’re good, we’re going in.”

Finally a wave took them off. As he felt the life ring line tugging, Gribble said, he feared it might have snagged after all, and let go to pop up in the churning sea. He tried to clear his head and get his bearings as thoughts raced.

At least he was not trapped in the wreck, with a chance his body could be recovered and returned to his family, he said. “I’ve found guys” after accidents, he testified. “They had their suits on, and they were dead. That was in daylight, in flat calm.”

He saw one of the Scandies Rose’s life rafts had inflated and was moving closer on the wind and current. “It took a few minutes but luckily I was able to get over to it.”

Gribble heaved himself in, finding the raft almost full of water, and began screaming out for Lawler. He heard the other man yell back and then swim over so Gribble could help him in.

With 30-foot swells they feared the raft would flip even with its water ballast and scrambled around to keep it stable.

They found the raft’s survival gear bag — tied down under the water, and perilously close to the raft’s open door with the heaving sea. They launched a flare, in hopes that Gary Cobban’s mayday call had brought a Coast Guard HC-130 search aircraft from Kodiak.

After six hours in the raft, they spotted a light on a second raft from the Scandies Rose — the spotting light on theirs had gone out — and what they at first thought was a vessel masthead light. It was a Coast Guard helicopter crew who recovered Gribble and Lawler and flew them back to Kodiak.

The board of inquiry is looking closely at witness testimony about corrosion and welding repairs to the Scandies Rose, including a location on the starboard side near a discard chute. Gribble mentioned that came up in the life raft.

“Jon was like, ‘I wonder if it had something to do with the welding job.’” Gribble said he replied, “Well, that’s a good time to find out about that, in the life raft.”

Gribble said he was the new crewman on the Scandies Rose and that he did not know the repair history. If he’d had that information about the weld repair on the starboard side, combined with the boat’s feeling of sluggishness that night, it might have raised the level of concern with Cobban, Gribble said.

Gribble said he had felt a twinge of unease after arriving at Kodiak to join the crew — he had flown up so the Scandies Rose could get out on time — but put it off.

“When I first got there, I had a funny feeling, but I thought I can’t do this to these guys and just quit on them,” he testified. He planned to make the one trip, he said. — Kirk Moore

Day 5 – Shelikof Strait: The blast freezer

The Scandies Rose sank on New Year’s Eve 2019 in waters notorious for blasting winds and spray that can swiftly ice up fishing vessels and threaten their stability, veteran Bering Sea captains testified Feb. 26 to the Coast Guard marine board of inquiry investigating the loss of five crewmen’s lives.

Daniel DeLaurentis, captain of the vessel Ruff & Reddy, told the board how he and his crew were outbound for pot cod season when “we began getting weather” in the Shelikof Strait. His wheel watch awoke him around 3 a.m.

With winds of 25 to 30 knots, icing conditions were setting in. The Ruff & Reddy anchored around 5 a.m. in the lee of an island, with a half-inch of ice on its rails, said DeLaurentis.

That evening a satellite phone call from their company dispatcher alerted them that the Coast Guard was requesting help after hearing a mayday radio call from the Scandies Rose, 28 miles away.

DeLaurentis said he had to decline.

“I could not travel with a load of gear” in those weather conditions, he told the board.

Captain Bryce Buholm, most recently master of the vessel Western Mariner, testified he learned about fishing and the region’s savage weather years before from Scandies Rose captain Gary Cobban Jr.

“It’s different up there than anywhere else in the world,” Buholm told the board. “The area where the Scandies went down has some of the worst icing I’ve seen.”

Buholm, a self-described “weather nerd,” said the region is characterized by northwest winds blowing 30 to 40 knots across the Alaska Peninsula and its mountain glaciers, with freezing precipitation and sea spray raining on boats.

“I call it the freezer hold of hell,” said Buholm. When underway, “we watch it very carefully. There’s written instructions in the wheelhouse to wake me.” A captain’s experienced judgement is always needed over deckhands’ impressions; less experienced hands easily underestimate icing, he said.

Buholm said he has “been caught out there” and had to spend days anchored in the lee of islands “breaking off ice” to get underway again.

In those waters, Buholm worked with Cobban in 2005, and in years later ran alongside him in the fisheries: “Gary was my partner boat forever.”

“There’s a lot of local knowledge that I was taught by Gary,” said Buholm. “Gary kept on top of everything. He was one of the top five captains I’ve known in my life.”

For principal owner Dan Mattsen and Mattsen Management “every boat had to live on its own” in budgeting, and the Scandies Rose made more money because of its crab quota, said Buholm. “The safety and integrity of the boat, they were never shy about spending money on that.”

Josh Songstand, master of the 126-foot Handler who formerly worked on the Scandies Rose, recalled the boat being kept in good shape, with some repair work done on cracked welds in a forepeak area used for storage and hydraulics. The board has been questioning witnesses about corrosion and cracked welds that were repaired there and under a bycatch chute on the vessel’s starboard.

Songstand said he passed by the Scandies Rose Dec. 29, when he and crew member thought it looked a little low in the water.

“It looked a little more squat in the water than I expected,” said Songstand, who had worked on the Scandies Rose as a deckhand years before. A rub rail was submerged and freeing ports appeared to be about six inches above the water, he said. They surmised the boat was loaded with what they estimated at around 200 pots.

Asked if fishermen are doing anything differently because of the sinking, Buholm replied: “There is no real change in what we do.”

“It’s crab fishing in the Bering Sea,” he added. “It’s not safe. We do what we’ve got to do.”

Still, the Scandies Rose loss was a shock. Buholm said it was the first house-aft vessel to roll over in the fishery.

Buholm offered what he thinks could have been a final sequence of events for the Scandies Rose sinking.

In his Feb. 24 testimony, Scandies Rose survivor Jon Lawler recalled hearing the engine throttles pulled back.

“The boat started going fast, like fast, after we lost that like forward momentum,” said Lawler.

As the vessel lost headway, seawater rolling across the deck as the vessel created free surface effect – immense force that would have rocked the boat farther over in its list, Buholm suggested. That would trigger downflooding, with seas pouring into any open hatch or opening.

“It’s the scariest thing on a boat, next to a fire,” he said.

Free surface effect and subsequent downflooding were cited as an under-estimated danger in a 1999 Coast Guard commercial fishing vessel safety task force report, undertaken after several East Coast surf clam vessels sank.

Investigators determined those boats were endangered by seawater in their clam holds, that fishermen had believed would help stabilize the boats as ballast. Instead, the rolling and sloshing momentum of water destabilized them.

The board chairman, Coast Guard Capt. Greg Callaghan, asked Buholm: “What needs to change to make it safer?”

“We need more training for the crew,” Buholm replied. Ideally it should all be done at Dutch Harbor, to simplify travel and allow crew members to focus as a group on safety, he said.

“It creates crew morale and teaches the guys to trust each other in those situations,” said Buholm.

In closing, Buholm spoke of the emotional toll of working in the Bering Sea fishery.

“I’ve been watching my family’s friends die since I was a little kid,” he said.

In 2003 it happened to him firsthand on a king crab trip, when a crewman fell overboard. Buholm said he pulled on an immersion suit, jumped in to grab the man, “and he dies in my arms.”

“And I had to face his mother, who had lost three sons in five years to the ocean, that next week when we buried him.”

After the loss of the vessel Destination in 2017, Coast Guard safety officials started a stability and pot weighing initiative to help fishermen understand loads better.

“It’s been really accepted by the industry,” testified Anthony Wilwert, commercial fishing vessel safety program manager for the 17th Coast Guard District in Juneau. The use of portable scales to sample and weigh pots with captains watching “really opened a lot of eyes” to their actual gear burdens, he said.

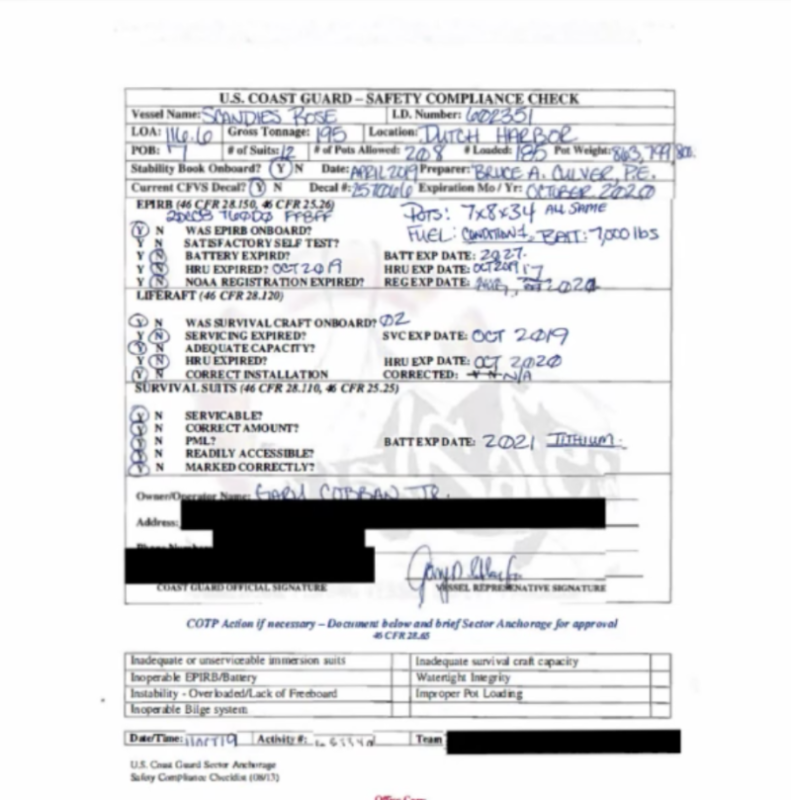

Cobban was carrying 192 pots on the trip, according to previous testimony from vessel owner Dan Mattsen. Reviewing a checklist from an Oct. 11, 2019, dockside safety and stability visit, Wilwert said examiners found the Scandies Rose had all its equipment and safety gear in order.

During an Oct. 14, 2018, check and pot weighing, the Sandies Rose stability book said 212 pots were the maximum, said Wilwert. At that time, Cobban told examiners he was planning to carry 170 on his next trip.

Buholm recalled a 90-minute telephone call with Cobban the day before the Scandies Rose departed. He chatted the captain with while stuck in traffic near his home in Seattle, as Cobban and his crew prepared to sail.

Among other things, they discussed stability and safety checks. Buholm said his last dockside exam led to downsizing the Western Mariner’s maximum pot numbers to “80-something.” But Cobban told Buholm the Scandies Rose number was unchanged after its last safety check. – Kirk Moore

Day 4 — Scandies skipper respected but hard charging

Two men with intimate knowledge of the Scandies Rose and her crew headlined the fourth day of the ongoing inquiry into the ship, which sank during a winter storm south of the Alaska Peninsula on Dec. 31, 2019, killing five of seven people on board. The testimonies of Cory Fanning and Peter Wilson, both former chief engineers on the Scandies Rose, helped paint a more nuanced portrait of the ship and its crew.

Fanning, who worked on the Scandies Rose for several years until 2018, described the Scandies Rose as a “battleship” and a “Cadillac” and twice during Thursday’s testimony called it an “incredible fishing platform”. During his years on the vessel, he also developed a close relationship with four of the crew who died in the accident, including the captain, Gary Cobban Jr., and his son, David Cobban.

Cobban Jr., whose dad, Gary Cobban Sr., was also an Alaska fishing captain, emerged as an especially challenging figure, a highly regarded fisherman but ambitious to a fault. Both Fanning and Wilson described Cobban Jr. as a well-respected, hard-charging lifer, who was driven to be the best in the fleet, an impulse that could tax those around him.

“Gary had been around a long time, fishing his whole life, since he was 12 or 13 or something. Gary worked hard. The crew worked. He maybe pushed too hard sometimes. He wanted to be the best at what he did, whatever that was, and maybe at times that didn’t make the crew so happy, but he was an incredible fisherman,” Fanning said.

When asked if Cobban Jr. ever worked the crew to “harmful fatigue,” Fanning chuckled.

“A typical day on the Scandies was 20 hours. Most days we would run and haul gear for 20 hours and then take a six-hour nap,” Fanning said, adding he did not know how to quantify harmful fatigue.

One of the day’s more emotional moments came when the soft-spoken Fanning, speaking on a satellite phone with a delay from the wheelhouse of the Aleutian Mariner, choked up while talking about David Cobban. Fishing clearly did not come easy to the younger Cobban, but he had won the respect of his colleagues.

“David is tough for me to talk about,” Fanning said haltingly. “David had turned into a pretty solid deckhand. It took him a long time to get there. I think he was the only six-year bait boy in existence. But he finally came around.”

No one described his dad as a slow learner. Wilson, who worked on the Scandies Rose from 2008 to 2014 as the chief engineer, said the captain had a reputation for being hyper-competitive and that he wanted to win. Under the tutelage of Cobban Jr., Wilson learned the ropes and went on to captain the New Venture, which he has been running for seven years.

“Gary was always known as an awesome fisherman, and as I got to work with him, he was a great captain. We all have our sides. Gary was hard, but he was fair. If he asked you to do something he wouldn’t do himself, he would push. But he also knew when to back off,” Wilson said.

Cobban Jr. may have pushed it, but three separate witnesses on Thursday refused to question his judgement for sailing out of Kodiak on the night the ship went down, despite repeated questions from the Coast Guard board.

Oystein Lone is the captain of the Pacific Sounder and likely the last person to talk to Cobban Jr. via telephone. On the night of the accident, he was 200 miles away, on anchor on the other side of the Alaska Peninsula after spending the day dropping his pots. He was not surprised Cobban Jr. was making his way toward the grounds.

“There were boats ahead of him and behind him. It was getting to be that time of year where fishing starts, so I wasn’t surprised,” Lone said.

Lone talked to Cobban Jr. twice that night. The first time — likely a little after 8:30 p.m. — Cobban Jr. confirmed he was dealing with tough weather; winds howled at 60 to 70 knots, and the temperature sat at 12 degrees F. Cobban Jr. also told Lone he had 195 pots on deck and that ice had built up on his starboard side, causing the ship to list to around 20 degrees. About five miles away from the Sutwick Island during the first call with Lone, Cobban Jr. had planned to tuck into the lee of the island and get cover for his crew to safely break ice.

“We chatted about some other stuff. There was no urgency in the call at that time,” Lone said.

Lone had to switch over a generator, so he told Cobban Jr. he would call him back. When he did call him back — Lone thinks it was 9:58 p.m., not long before Cobban Jr.’s mayday call — the mood aboard the Scandies Rose had shifted dramatically.

“He was definitely very concerned at that point. I could hear it in his voice. There was fear in his voice,” Lone said.

Lone remembers Cobban Jr. saying that the list had worsened and “that he did not know how this was going to go.” Then Lone lost connection.

Lone estimated that night he had 6 inches of ice on the railings of his boat, and much of the Coast Guard’s questions on the day centered on icing and the reliability of stability tests, especially when ice and crab pots are involved.

The Coast Guard Marine Board of Investigation hopes to pinpoint probable cause in the accident and make recommendations that might improve safety for vessels in the North Pacific, especially when it comes to icing.

Lone said the Scandies Rose and the Destination before it have prompted fishermen to do some of their own work.

“We’re kind of looking in the mirror a little bit, all of us. We’ve taken some steps here to try to start some stability classes. It’s baby steps, but we’re trying to make some positive moves out of this and learn from it,” Lone said.

Through four days of the trial, Coast Guard and National Transportation Safety Board investigators seem to be developing a narrative of a ship that took on too much ice and began to list, which caused water to rush in somewhere, causing downflooding that sunk the boat quickly. The point or points of entry for the water are of particular interest to the board.

But Wilson, in one of the more candid moments of the day, openly doubted whether even such a thorough inquiry will turn up exactly what went wrong that night.

“I’m a captain entrusted with anywhere from two to five lives. And those lives are depending on me to bring a boat back, to see their families again. Gary was a captain, too. It’s just very unfortunate what happened here. We’ll never know the truth. We can all speculate, but the only people who really know what happened on the boat unfortunately are no longer with us,” Wilson said.

The tone of the day, which shifted between solemn and technical, got some air in the afternoon with the appearance of Dillion Gamby, a one-time deckhand on the Scandies Rose who narrowly avoided the incident.

Sporting a black button-down, a mohawk, and a subtle mustache, Gamby explained that he was the bait boy for red king crab on the Scandies earlier in 2019 and that his responsibilities included “doing everything he was asked to do.” He had signed on for the opie season — the trip that ended in tragedy — amidst warnings from the Scandies crew that is was a different kind of season: “intense, dangerous, and not a walk in the park.”

An incident while loading pots in the snow shortly before leaving, however, led him believe he was not cut out for it and decided to stay home.

“I realized that if I go out there, there’s a chance I might not come back, or I might hurt others. I never feared the boat going down. The fear was of me falling off the boat, or hurting someone else,” Gamby said. — Brian Hagenbuch

Day 3 — Scandies Rose survivor Jon Lawler recalls sinking

“I worked on a boat called the Destination… I thought about those guys all the time,” said Scandies Rose survivor Jon Lawler in his testimony, on Wednesday, Feb. 25. “I used to always play this back in my head: How would I get out of a boat? You know you can’t get out of a boat when it’s upside down.”

The Dec. 30, 2019, trip had begun with three days of nonstop gear work, according to Lawler. They were bustling to switch the pots for what was likely a short pot-cod season before they moved on to catching opies. Lawler said they seemed to be in a hurry to get out, and that cod season was possibly why. The over-60 cod boats had had a short season the year before, starting on Jan. 1.

“The year prior to this, their season closed on the sixth of January,” Lawler said. “They only had enough time to get their gear out in the water, barely make a trip, and then they had to stack out again.”

So they loaded the boat with pots. Dan Mattsen testified that skipper Gary Cobban reported they had 192 pots onboard.

“I think it was pushing up over 200 a little ways,” Lawler testified. “From port to starboard, every spot was full there. Literally every square inch of that deck was pots.”

They had been working long days on the gear, and Lawler thought between the tired crew and the forecast, they’d leave the next day.

“You know we’d been working our asses off getting the boat ready. And then we heard the weather forecast. And I’m thinking, ‘Oh the boys are gonna have a bar night. We’re gonna go into town and get some beers because we’re definitely not leaving in that.’”

He remembered Cobban talking to the crew about the weather.

“We’re gonna run into some shit. And that shit’s gonna become a lot of shit. But make sure everything is tied down good.”

While they waited for the tide, Cobban reviewed safety procedures and equipment with the crew.

“It was just an eerie night, man,” Lawler said. “Gary [Cobban] made this comment about how you don’t leave the boat, the boat leaves you.”

He testified that Cobban had accidentally hit the emergency button on the EPIRB, but Lawler didn’t see a light, even though they were in a dark wheelhouse.

“I knew we were leaving into a storm, and it just didn’t feel right,” Lawler said. “Nothing about it felt right.”

They took turns on wheel watch, an hour on, he reported. He had been watching the movie “Ford vs. Ferarri” in his bunk and was about to nod off.

“And we were never listing a little bit at all. It was trim, good to go,” Lawler said. “But then all of a sudden, I rolled into my bunk. And this sheer terror comes over me. I knew something was wrong. So I ran upstairs. And I look at Gary, and I just go, ‘What the fuck’s going on? What’s going on?’

“And he goes, ‘I don’t know what’s going on.’ He says, ‘I think we’re fucking sinking.’ And I go, ‘No fucking shit we’re sinking.’

“And I’m just trying to figure out how did it go from nothing to the boat’s literally like leaving us now.

“I just started yelling because there was no alarm going off.”

Lawler yelled down to wake up anyone who was sleeping and remembered Dean being up there within seconds.

“Something clicked in my head that it wasn’t right,” Lawler said. “There was just white noise all around you, and pure panic. People were there. I couldn’t tell you who was who.”

“The only thing I do remember in that moment was the green suit’s the big one, and I need to move fast.

“Just muscle, muscle memory. I don’t know what it was, it was just fight or flight.

“The people in the wheelhouse I could hear, ‘Oh god. Oh god. Oh god,’ over and over and over again, you know from other people around me. No one was using their words. It was just sheer panic.

“I think at one point, I did heard Gary [Cobban] say something about like, ‘I don’t know what to do.’ And I heard somebody say, ‘You need to call the Coast Guard now.’”

“As I’m getting my suit on, there’s people around me. I do remember looking up, and the throttles got pulled back on the boat. And then it just, it was downhill from there. The boat started going fast, like fast, after we lost that like forward momentum.

“And the one thing that’s burned in my brain that I can’t get rid of is I stood over Mr. [Brock] Rainey. The pitch of the boat was so steep, I was hanging onto the things the things that you hear shit crashing off, all the shelves.

“He grabs me by my suit, pulling on me, ‘Help me, Jonny! Help me!’ And I didn’t help him. He wasn’t even in his suit. He barely had his feet in. And I just knew I needed to leave the boat. I had to make that decision. I had to go. That’s what I did. I got up to the port door barely just climbing on things. And I went out, and the wind hit my face. I just kept telling myself in my head. I gotta get the suit on, gotta get outside.”

“I worked on a boat called the Destination… I thought about those guys all the time. I used to always play this back in my head: How would I get out of a boat? You know you can’t get out of a boat when it’s upside down.”

“So I just had to get out. I got out. And I was outside, and still trying to get my zipper up. Couldn’t get my zipper up. And the wind was just howling out there. There was ice all over the rails. And I just remember hearing Deano [Gribble] yelling at me, ‘Jonny!… ‘What are we doing?’”

“And I go, ‘I don’t know what we’re doing. We’re going for a swim, that’s all I can say.’

“And I told him I couldn’t get my zipper up, and he started freaking out, trying to help me. But I just, I couldn’t help anybody. There was not enough time to help anybody. Everyone had to help themselves.”

Gribble suggested getting a raft, but Lawler was worried about getting hung up in the rigging.

“I was just expecting to go in the water. That’s all I knew. And I was hoping people were going to follow me out.

“No alarm was going off, like I said. That’s why I know Gary [Cobban] made that mayday call after I was outside, because the alarm was going off in the back of that mayday call. And the alarm didn’t start sounding finally until we listed hard enough over. So what my theory… is that, the mains, the auxiliaries, they lost engine oil pressure. And they started running away, and the stacks were blowing black smoke out. And then you just felt the whole boat shudder. Then lights out. And all you could hear was the ocean.

“You couldn’t really hear anybody inside anymore, which was the eeriest thing. Cause I think, you know, a lot of people were up on the high side with me. But when the boat listed over, I think they all just slid right down the floor and smashed into the wall on the other side. I still don’t understand why they didn’t go out the starboard door. There was an opportunity for everyone to get out. It doesn’t make any sense.”

“I sleep on it. I daydream about it. I play it back over and over and over again, trying to change it in my head,” Lawler said.

“From the time I left my bunk to the time I was in the water. I mean, I didn’t have a watch on me, but I would gauge 10 minutes we were in the water.

“Before we went in the water, we didn’t know we were going in the water. And that’s why I reverted back to what I said prior that you don’t leave the boat. The boat leaves you. Because there’s been stories like that of you guys [the Coast Guard] finding boats that are sitting there barely bobbing and no crew to be found. So I just stood on it as long as I could. I followed the boat around. I sat on the superstructure, crawled around to the port side. Put my hand in one of scuppers. And by then the water was halfway up my shins, towards my knees. And I heard Deano [Gribble] say, ‘Here it comes.’

“And I look up to the side, and this fucking wall of water just blew us off, and I didn’t have my bladder blown up. I was upside down, like a washing machine. Couldn’t breathe, I was sucking in seawater. And then finally… I was able to somehow calm myself down enough to where I could just loosen my body up and just breathe. Just try and catch any gasp of air I could get. And that’s, that’s all I have. I mean, I thought I was dead the whole time.

“The bow of the boat was up. You could hear it, too. I still hear it. You would think something that big wouldn’t be able to just get tossed around that hard. We had water somewhere. There had to have been water somewhere, because it went down so fast.

“It just sat up for a second and was bashing back and forth, and you could hear the steel,” Lawler said.

“I remember looking at the boat, paddling backwards, as hard as I could. Then one second, it just like a rocket, just down, gone. Nothing but silence, just me, the ocean. And I say the ocean like nicely, it was very violent that night.

“I was just accepting, acceptance at that point. I wasn’t going home. I mean the fact that raft showed up. I don’t know what to think about that.

“I heard Deano [Gribble] yelling at me. I barely had enough room to look over my neck, and there he was sitting in the raft. And I just couldn’t believe it.

“I got in it, and at that point. It was nice to know someone else was there.”

Lawler described using their flares, big seas and trying to talk to each other to prevent slipping away. He noticed the other life raft and kept hoping to see signs of other crew. On one of his checks, he saw a light and realized it was a Coast Guard helicopter.

“They were hovering over us, and that was the most beautiful sound I’ve ever heard in my life.”

Throughout Lawler’s testimony, it was clear he believed the sinking was at least exacerbated by downflooding.

“One thing I noticed on this boat was that the watertight door that separates the one part of the engine room to the next, where those voids were, was always stuck open. It was never dogged shut,” Lawler said. “I think I actually asked Art [Ganacias] about that, and he said they always leave it open. And that could have probably bought us some time, too, just having that dogged, in the downward flooding.”

Earlier in the day, Paul Zankich, Bud Bronson and Jonathan Parrott, comprised a panel of naval architects testifying on vessel stability, icing and gear loading.

The panel discussed the failure of International Maritime Organization guidelines to account for ice accumulation inside of pots on a Bering Sea boat deck.

“We really don’t and didn’t have any good information on how a crab pot ices, so we used the IMO criteria, which says use the outside of the crab pot,” said Bronson. “And a crab pot isn’t really a box. It’s this sieve that collects ice all through it.”

The panel members referred to the IMO’s “shoebox” analogy, which assumes ice collecting on vertical and horizontal surfaces but not inside the webbing because the standards are general and are not written specifically for that kind of gear on deck.

“We understand how the IMO came up with the standards they have for icing,” Bronson added. “But the crab fishery in the Northwest Pacific is significantly different than anywhere else.”

Zankich specifically pressed for better data specific to pot gear.

“If you’re a crabber, you have to believe the Coast Guard standards, you have to believe the IMO standards, you have to believe your naval architect,” he said. “All of these three beliefs need review in this inquiry, because we are the naval architects who are asking our owners and operators to believe. And we rely upon the Coast Guard standard to believe and the IMO standard to believe. And honestly, I don’t believe those standards now.”

Regulations account for as much as 6/10 of an inch of ice accumulation on vertical surfaces and 1.3 inches on horizontal surfaces — and uniform accumulation on those surfaces.

“Crab pots… can accumulate ice on the inside of the pots,” said Parrott. “And if you’ve got wind and weather coming from a certain direction, the pots on that side are going to be heavier, are going to accumulate more ice in it than pots on the other side.”

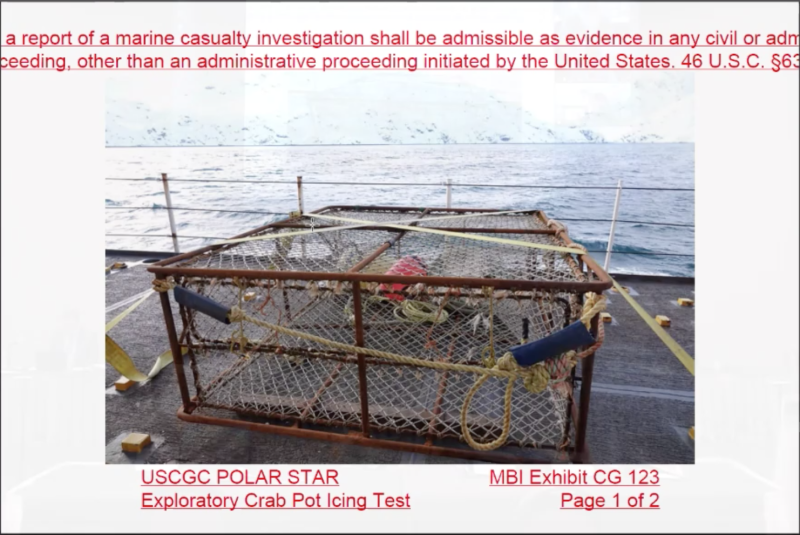

After this testimony, Capt. Callaghan called for a brief recess to introduce some new evidence.

He then presented an image of a single 1,000-pound pot on an otherwise empty deck. The Coast Guard had reportedly experimented with the pot, spraying it with a hose to weigh it out after it was iced up.

They were not able to get an accurate weight because the iced up pot maxed out their 3,000-pound scale. And that pot is not completely iced in.

Parrott made the point that better data on pots is critical for the Bering Sea crab fishery but also because pot fisheries are expanding in Alaska. — Jessica Hathaway

Day 2 —“The Scandies Rose was built to last”

Day two of the two-week inquiry into the crabbing vessel the Scandies Rose focused on welds and weather as the Coast Guard Marine Board of Investigation attempted to pinpoint what caused a seemingly well-built, well-maintained vessel to capsize on Dec. 31, 2019.

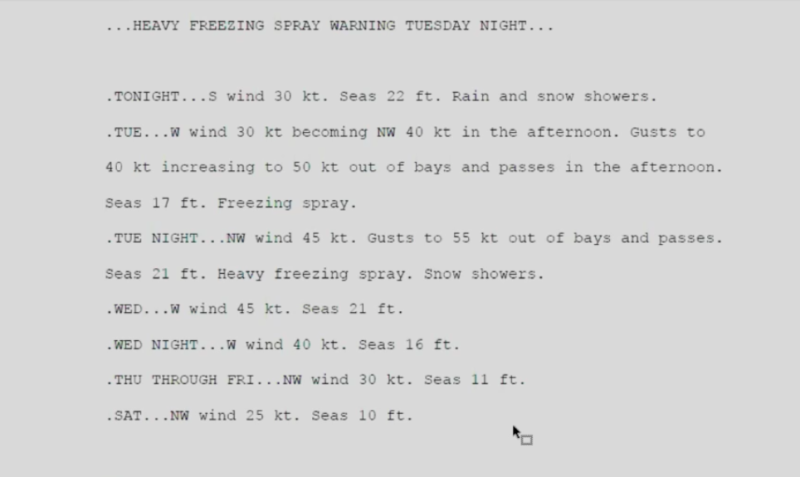

In the morning session, the Coast Guard panel and members of the National Transportation Safety Board heard testimony from Noelle Runyan, a meteorologist for the National Weather Service in Anchorage.

Questions for Runyan centered around how the regional NWS office assesses and issues warnings about heavy weather — in particular the critical freezing spray warnings — and what kind of warnings were issued before the Scandies Rose went down.

Runyan noted the NWS forecast for Dec. 31 showed ominous winds building during the day, with warnings of gale force winds and heavy freezing spray headlining the night’s forecast.

“During the day, it’s showing west winds at 30 knots, increasing in the afternoon, gusts increasing, especially in the bays and passes. Freezing spray, seas 17 feet. Then, when I look at Tuesday night, I see that seas are expected to be worse,” Runyan said.

Runyan said the wind and seas that battered the Scandies Rose were high, in line with a strong winter storms in the area.

Later in the day, the board heard testimony from two men familiar with the ship, both who said the Scandies Rose was a solidly built, well-maintained vessel.

Ed Ehler, the project manager at Lovrics SeaCraft in Anacortes, Wash., had worked through a maintenance checklist for the boat in April of 2019. He said Scandies Rose principal owner Dan Mattsen — who is also the captain of the Amatuli and has ownership stakes in the New Venture and the Alaska Challenger — has a reputation for taking good care of his vessels.

“What I can say about the Scandies Rose and (Mattsen’s) other boats is that he does maintain them better so than most that I see in this yard. The upkeep is somewhat above average,” Ehler said.

Long-time marine surveyor Erling Jacobsen inspected the Scandies Rose several times over the last two decades. He echoed Ehler’s comments.

“They always took very good care of the vessel, and I was impressed with the way they kept it maintained. They tried to address problems on the vessel the best they could. They just did a great job,” Jacobsen said.

Jacobsen added that the hull was one of the best he had seen come off Bender Shipbuilding’s yard in Mobile, Ala.

“The Scandies Rose was built to last,” Jacobsen said.

Built to last, but very clearly something went wrong. Investigators zeroed in on a large, aft chute on the starboard side, alternatively referred to as the waste, overboard, or trash chute, and labeled the “shit chute” in texts from late Scandies Rose skipper Gary Cobban Jr.

Rusting steel in the chute had prompted a couple repairs in 2018 and 2019, but the crew found it was still leaking while they were getting ready for the 2020 winter crab season.

They hired Highmark Marine Fabrication in Kodiak, where welder Jordan Young did the work. He said the previous fixes on the chute had not rooted out the corrosion.

“They did a doubler, so they didn’t replace the wasted metal, they just put a patch over the top of it… There was significant wasting, and my job was to cut it out, get down to solid metal, and install all new material,” Young said, adding that it was his understanding the crew of the Scandies Rose had coated the leaky panels in Splash Zone or a similar epoxy.

Young estimated he spent seven or eight days on the project, and records show he used 66 square feet of steel.

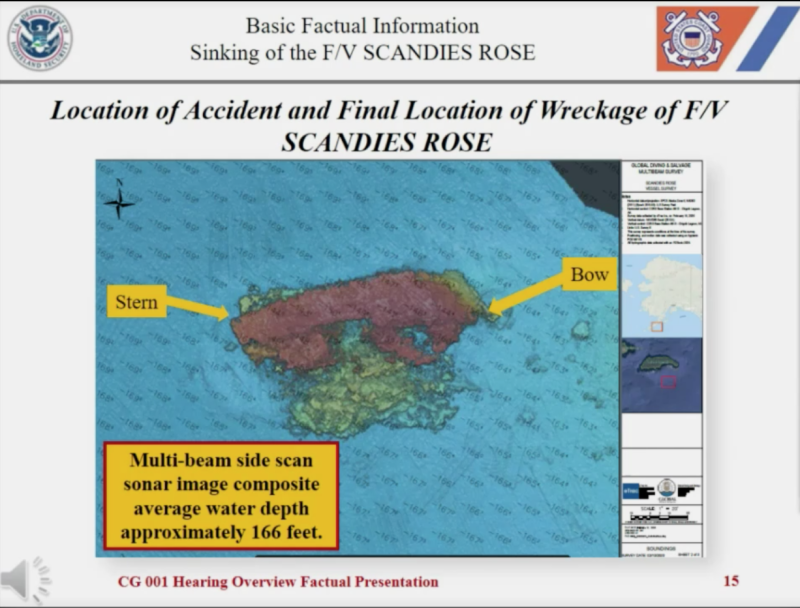

Kerry Walsh, the project manager for Global Diving and Salvage, led a team that surveyed the wreckage in February 2020.

“Before we left the dock, it was obvious there were questions about the fabrication work that went down prior to the ship sailing and that was a potential cause for her having gone down. Our job was look and see what we could see,” said Walsh.

His team sent a Falcon ROV to take images and video of the wreckage, but Walsh said the vessel was on its starboard side, and they could not access the chute.

“There is no obvious reason, no obvious sign why it went down in our eyes,” he said.

The Scandies Rose sunk after a mayday call at 10 p.m. on New Year’s Eve of 2019 while it was steaming along the south end of the Alaska Peninsula near Sutwick Island. Four of the six crew members died. The tragedy came two years after another crab boat, the F/V Destination, capsized in Alaska, killing all six people onboard.

According to reporting by the Seattle Times, over 70 crew members on crab boats died during the 1990s, but no one died from a crab boat sinking from 2006 to 2016. — Brian Hagenbuch

-----------------

Day one — the Destination is still on our minds

The hearings began this morning, Monday, Feb. 22, by setting the scene of the accident — the boat's last known location, weather conditions and the locations and names of other fishing boats in the area at the time.

Throughout the hearings one theme carried across all witnesses — shock that this could have happened to the Scandies Rose.

The first witness to testify was Dan Mattsen, principal of Mattsen Management, 51 percent owner of the Scandies Rose, and the captain of the Amatuli, which is primarily a tender vessel now.

Mattsen also has ownership stakes in the New Venture and the Alaska Challenger.

According to John Walsh, who testified at the end of the day, it was around 2012 that then-owner Leif Larsen was looking to sell the Scandies Rose.

Mattsen put together a partnership with Scandies Rose Captain Gary Cobban, Walsh and three partners from Alaskan Leader Fisheries.

After several years the Alaskan Leader partners were building a new factory longliner and wanted to be bought out.

“That's the genesis of the Scandies Rose Fishing Co.,” Mattsen said.

Though the boat was hauled out in 2019 for regular maintenance, some welding work was done at the Ocean Beauty dock by an independent welding crew and overseen by Mattsen.

“There's a void underneath [the starboard crab waste disposal chute] from the forepeak to the engine room, and Gary [Cobban] noticed there was water in it,” Mattsen testified. “It turned out to be a crappy weld job. So they had it redone before the winter crab season.”

The owners had also had a new stability test completed following the loss of the Destination. Bruce Culver had done the 1988 stability report. So in spring of 2019, Culver did a new stability report

The report determined that the Scandies Rose could carry 208 835-pound pots in non-icing or icing conditions.

"It would be very difficult to get 208 pots on that boat… under actual fishing conditions,” said Mattsen, “So the fact that they put a limit that was more than we were going to carry was good news for us. We thought it was good news."

“There’s been a lot of numbers talked about, how many pots were on the boat,” Mattsen said in response to a question from Barnum of the NTSB. “Gary told me it was 192 pots. Gary would know better than anybody how many pots were actually on the boat. So that's the number I'm going to use.”

Following some questions about Cobban’s lack of a captain’s license, Mattsen assured the investigators of his qualifications by way of a lifetime of experience.

“Gary's been running boats since he was 16 years old. His father owned the boat. You know he couldn't get a license — he's color blind,” Mattsen said. “Other than that, Gary had no problems. He's a captain.”

When Mattsen’s testimony was turned over to Barton Barnum of the NTSB, a miscommunication led to the most fiery moment of the day.

Barnum asked Mattsen what naval architects performed stability reports on his other vessels.

Mattsen replied it had been Seattle-based Hal Hockema’s group: “I trust Hal. So he sent his team out to do the incline test.”

Barnum: “It was different than the Scandies Rose naval architect?”

Mattsen: “Yes.”

Barnum: “And why was that?”

Mattsen: “Excuse my French, but my fucking boat sank. So I wasn't going to go back to the same naval architect until we found out what the hell was the cause of that.”

Barnum, looking taken aback, and realizing that Hockema’s group had overseen a new test after the Scandies Rose sinking, rather than before: “It was my misunderstanding. I thought you had gotten new stability instructions prior.”

Captain Greg Callaghan, chief of Prevention for the 11th Coast Guard District Chairman of the Coast Guard Marine Board of Investigation is the presiding officer over these proceedings.

Coast Guard questioning was led by Coast Guard Cmdr. Karen Denny with Barton Barnum, a representative present from the National Transportation Safety Board, as well as counsel for the witnesses and a representative for the surviving crew members.

Queries focused on who owned the boat, what their responsibilities were in regular operations and decision making, and how much their more recent decisions may have been informed by the reports of the Destination sinking.

Icing, gear weight, maintenance, crew hiring protocols, training, medical history of the crew, and general stability were key topics of the day.

“The marine board planned this two-week hearing to examine all events relating to the loss of the Scandies Rose and five crew members,” Callaghan said. “The hearing will explore crew member duties and qualifications, shoreside support operations, vessel stability, weather factors, effects of icing, safety equipment, the operation of the vessel from the past up to and including the accident voyage, survey imagery of the vessel in its final resting place. The hearing will also include a review of industry and regulatory safety programs, as well as the U.S. Coast Guard search and rescue activities related to the response phase of the accident after notification that the Scandies Rose was in distress.” — Jessica Hathaway

----------------

Thursday, Feb. 18

The U.S. Coast Guard is scheduled to convene a formal hearing on the loss of the Bering Sea crab boat Scandies Rose, starting Monday, Feb. 22.

Check back here for NF’s daily updates from the hearing, which is scheduled to run weekdays through Friday, March 5, beginning at 8 a.m. Pacific.

The hearing will stream live from Washington's Edmonds Center for the Arts.

The 130-foot Scandies Rose and five of her seven-man crew were lost on Dec. 31, 2019. John Lawler and Dean Gribble Jr., made it into survival suits and a life raft. They were rescued by the Coast Guard, which convened a Marine Board of Investigation into the sinking.

Those lost at sea were the boat's longtime captain, Gary Cobban Jr., 60; his son, David Cobban, 30; Seth Rosseau-Gano, 31; Arthur Ganacias, 50; and Brock Rainey, 47.

The survivors and the families of those lost reached an agreement with the owners of the Scandies Rose for more than $9 million in a settlement.