Fishing seasons are never the same. Variables make yearly swings the norm, and unpredictability means processing plants must be well-staffed and ready for any eventual harvest. But even for an industry used to volatility, 2020 has been a year like no other.

Seafood processors saw the costs of doing business skyrocket early this year as the covid-19 pandemic created widespread health and safety concerns. The disruption came just as the industry was preparing to hire for the summer salmon season.

Thousands of workers come to Alaska each year to process the catch, and most arrive in the spring and summer. The summer salmon harvest is the state’s highest-value and most labor-intensive. The first surge comes in June as processing employment doubles from about 6,000 jobs in recent years to 12,000 or 13,000. The job numbers peak in July between 20,000 and 21,000.

Because processing takes place as close to the harvest as possible, remote worksites with no local workforce are common. Some processors hire workers from around Alaska, but most of their employees are from out of state or are foreign workers under the H-2 visa program. For every Alaskan working in the plants, processing companies import three from outside the state.

Demand for the product changed

Alaska’s wild crab, halibut, and salmon have always been a hot commodity for restaurants. Just as high-end restaurants get the superior cuts of beef, they buy the best of the world’s seafood that’s bound for the U.S. market.

Restaurants closed nationwide in the spring, and when they reopened for takeout or limited service, seafood was seldom on the menu.

Demand for frozen fillets at grocery stores increased as people at home cooked more often, but global demand for seafood fell overall. Until people are eating out regularly, demand for the product will remain reduced and more seafood will end up in grocery stores than usual.

Safety concerns, mitigation costs

As covid-19 spread globally in February and March, small, coastal Alaska communities increasingly feared the arrival of thousands of commercial fishermen and seafood processors. For some communities, covid-19 raised the specter of past pandemics, such as the 1918 flu. That virus entered isolated villages on the coattails of outsiders and killed more people per capita in Alaska than anywhere in the world besides Samoa.

Early this year, the city of Dillingham and the Curyung tribe unsuccessfully petitioned Gov. Mike Dunleavy to close the commercial salmon fishery. In March, the governor declared fish harvesting and processing “essential services.”

The state issued health mandates in late April and May for out-of-state fish harvesters and processors. These included mandatory two-week quarantines, often at hotels in hubs such as Anchorage and Juneau, and testing at around $175 per test, at processors’ expense. As a result, the industry sank thousands of dollars into each employee before work even began.

Travel costs also increased. The pandemic sidelined flights both to Alaska and to the remote worksites, and the flight shortage was exacerbated by the April exit of Ravn Air Group, a major service provider to western Alaska.

Airline travel remained restricted in May as thousands of seafood processing workers were due to start work. Some companies chartered flights to transport workers and keep them isolated.

Outbreaks and other obstacles

According to a study by Intrafish Media, processors spent an estimated $50 million on additional cleaning, staff, masks, gloves, hand sanitizer, thermometers, quarantines, facility changes, and occasionally on-site health care, but the industry still hit rough patches.

Processing conditions are ideal for spreading a virus once it gets in. Seafood processors work close to each other for long hours in cold, wet environments. They also live together in group quarters, often in remote places with limited access to emergency medical services.

A few processing plants had to close for cleaning and quarantine of exposed staff after outbreaks:

In June, Whittier Seafood isolated and moved 11 workers to Anchorage to quarantine after they tested positive.

An OBI plant in Seward handled an outbreak in July of nearly 100 cases. A single positive case prompted the company to test all 262 employees, which turned up 96 positives.

Late July brought an outbreak on the floating processor American Triumph, which is part of the American Seafoods fleet. The crew reported symptoms and were tested when the vessel arrived in Dutch Harbor. Out of the 119 workers, 85 tested positive. The company moved the vessel to Seward, then transported the workers to Anchorage for isolation and treatment.

Others faced outbreaks after their resident workers contracted the virus in the surrounding community. While nonresident processors were forbidden to mingle with locals, local workers faced no such restrictions. Alaska Glacier Seafoods in Juneau attributed its July outbreak among 40 workers to transmission from the community.

Other problems arose before workers even reached Alaska. In June, North Pacific Seafoods hired 150 workers from California and Mexico to work in Naknek through August. Several tested positive before leaving California, so the entire group was quarantined at a Los Angeles hotel for two weeks with no pay and heavy restrictions. The company is being sued for wages and false imprisonment.

While there’s no cost estimate for these additional interruptions, they created another layer of pandemic-related expenses for the seafood processing industry to absorb.

Residents drove the caseloads

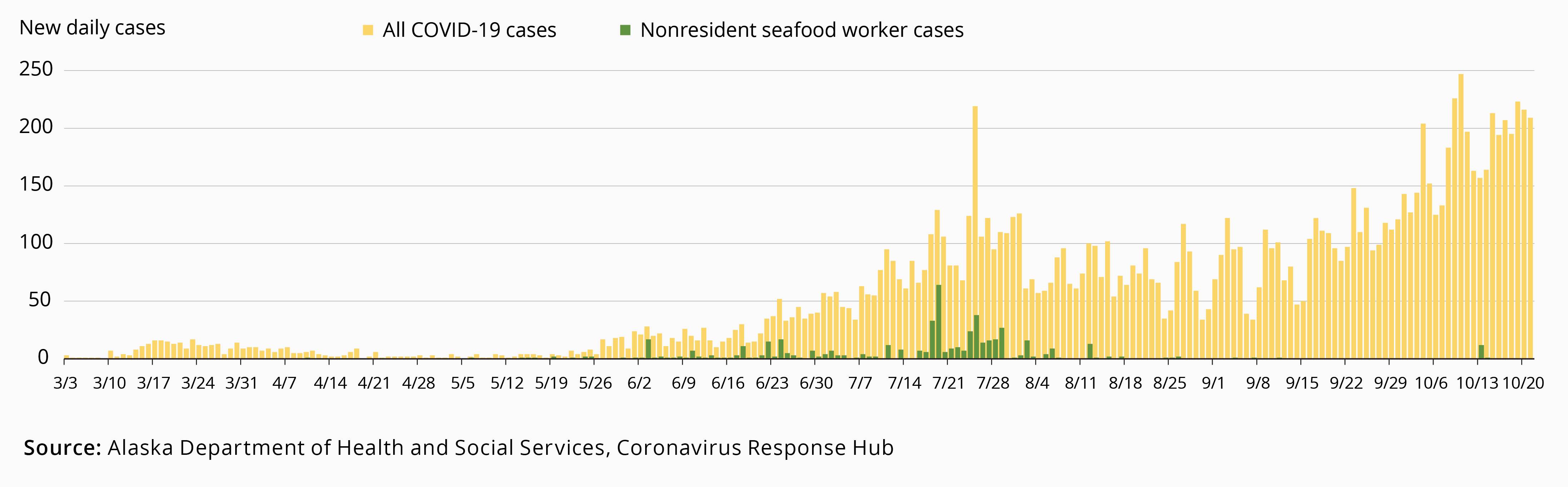

The number of covid-19 cases among nonresident seafood processors were tracked with the monthly job numbers, increasing from less than 15 earlier in the year to about 115 in June, then nearly tripling to 325 cases in July. As the salmon season wound down, so did their case numbers. August was the second-busiest month, but nonresident processor cases fell to around 60. There have been fewer than 20 cases since.

Even though thousands of nonresident processors worked in Alaska this spring and summer, they ultimately brought fewer cases into the state than communities feared.

Although public reports show some companies cut corners, such as shortening quarantine periods, the measures the state and companies took mostly worked. When the virus popped up, plants identified and isolated positive cases quickly, which kept the virus from spreading into the surrounding towns.

Alaskans drove the caseloads. Resident covid-19 cases dwarfed nonresident cases all year and accelerated as fall began. In September and October, with the summer workers mostly gone, residents pushed daily cases far higher than they’d been at any point during the summer.

In terms of new cases per month, resident cases grew from about 2,100 in August to 2,700 in September, and the first three weeks of October recorded 3,700.

How the pandemic affected jobs

Early in 2020, before the pandemic, seafood processing employment was up slightly from 2019 levels. While salmon is the headliner, processing is a year-round effort. Harvesting crab and a handful of other species requires a base of at least a couple thousand jobs in December, the lowest point of the annual cycle.

Employment increases by 5,000 or 6,000 jobs as the Pacific cod season opens each January, and then the industry contracts a bit from March to May — a breather between the winter fisheries and the salmon season.

April showed the first signs of disruption. April’s job count of 6,700 was about 1,000 lower than the previous April. Processing plants likely suspended some operations that month as they changed operations and assessed vulnerability.

Our data provide a solid picture of jobs through June and preliminary estimates through September. Employment was down about 700 in June, and our estimates suggest that pattern continued. The season progressed to its July peak and its second-highest month, August, with about 2,000 fewer jobs each month than in 2019. That’s an estimated drop of about 13 percent.

Despite the additional time and expense required, operators brought on a typical-sized workforce this year. That’s because the details of the salmon harvest are unknown until it’s well underway, and even then, how many the boats deliver can be a surprise from day to day. Processing plants have to prepare for any effort necessary.

The 2020 salmon harvest proved relatively weak. While Bristol Bay’s sockeye runs were strong, the state’s total sockeye harvest was 15 percent below its five-year average. Bristol Bay caught the bulk of the state’s sockeye and brought in more coho than last year.

Without Bristol Bay’s strong year, the state’s salmon harvest would have been the lowest since 1976. The pink harvest was about 25 percent lower than its 10-year average, although up considerably from 2018. (The size of pink salmon runs cycles in alternate years.) The chum harvest, also known as keta, was the smallest since 1979.

The Aleutians and the Alaska Peninsula brought in more than four times more pinks this year than they did in 2018 but caught fewer high-value sockeyes, which are usually their bread and butter. Chignik remained closed for a second consecutive season in 2020.

Kodiak harvested far more pinks than anticipated, but Southeast brought in less than half the expected sockeye and chum harvests, and the coho harvest wasn’t much better. Runs were so bad in Southeast that Cordova, Petersburg, and Ketchikan declared local disasters and will seek emergency funds.

State will disburse $50 million in federal pandemic relief funds

The state received $50 million in federal CARES Act pandemic relief funds for the fishing industry and is deciding how to distribute it. The plan was preliminary at press time but suggests the state would split the money into thirds for Alaska-based seafood harvesters, processors, and subsistence/aquaculture/commercial sport charter fishing.

Originally published by the Alaska Department of Labor and Workforce Development in its Alaska Economic Trends November 2020 newsletter.