Opening four dams on the Lower Snake River are the key to restoring salmon and steelhead in the Northwest river basin, according to a final recovery plan from the National Marine Fisheries Service.

“For Snake River stocks, the centerpiece action is restoring the lower Snake River via dam breaching. Restoring more normalized reach-scale hydrology and hydraulics, and thus river conditions and function in the lower Snake River, requires dam breaching,” the NMFS document states.

Opening the dams will speed water and juvenile fish in the river, reduce the stress on fish passing through hydroelectric powerhouses, and provide “additional rearing and spawning habitat” for fish in the river, the plan says.

Letting the Columbia flow unimpeded by the Bonneville Dam and three other is key to bringing back salmon in the river basin, Rob Masonis, Trout Unlimited’s vice president of Western conservation, told Oregon Public Radio.

“If you don’t have that foundation, the billions of dollars that we have spent, and will spend in the future, will not produce the desired outcome of salmon recovery,” Masonis said. “We need to remove the big bottleneck that’s preventing us from realizing the benefit of those investments and that’s the four dams on the Lower Snake River.”

Hydroelectric power from Northwest dams powered the region’s industrial development in the 20th century. Now with the state and federal government agencies scrambling to secure renewable energy supplies to carbon emissions, climate change is likely to force a new balancing between energy and wildlife needs.

“There is no clean energy future in Washington State and throughout the Pacific Northwest without these hydroelectric dams,” Rep. Dan Newhouse, R-Washington, said after the NMFS report.

Newhouse said the “Biden administration is playing politics with its energy future while ignoring recent data showing spring and summer chinook returns at higher levels than they have been in years. Factors like ocean conditions, predation, and others need to be considered and would be considered if this was a serious rulemaking process with an official public comment period, Congressional input, and coordination with other federal agencies who would be severely impacted by the outcomes this report suggests.”

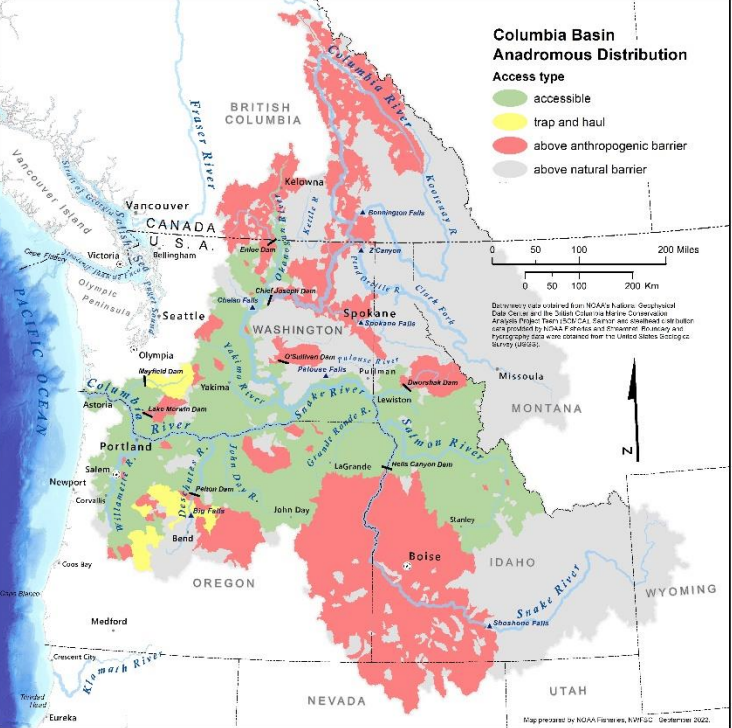

The report recommends an extensive “suite of actions to rebuild Columbia Basin stocks include: increasing habitat restoration, reintroducing salmon into blocked areas, breaching dams, managing predators, reforming fish hatcheries and harvest and reconnecting floodplain habitat.”

“This is a crucial time for the Columbia Basin’s salmon and steelhead. They face increasing pressure from climate change and other longstanding stressors including water quality and fish blockages caused by dams,” said Janet Coit, assistant administrator for NOAA Fisheries and acting assistant secretary of commerce for oceans and atmosphere at NOAA. “The report identifies goals for the recovery of salmon and steelhead that will require a sustained commitment over many decades.”

The report is not a regulatory action by NOAA, “but rather is intended to inform and contribute to regional conversations and funding decisions,” according to the agency. The goal going back to the Columbia Basin Partnership’s 2020 recommendations is that efforts should go beyond staving off extinction of native salmon and steelhead, but rebuild to “healthy and harvestable numbers that contribute fully to the culture, environment and economy of the region.”

The report ranks restoration priorities highest for the Snake River spring and summer chinook salmon, Snake River steelhead, upper Columbia River fall Chinook, upper Columbia River spring chinook, upper Columbia River summer chinook, and upper Columbia steelhead.

“With the exception of upper Columbia fall chinook and upper Columbia summer chinook, this approach prioritizes stocks that are at high risk of extinction,” the report says.

Earlier attempts to revive Northwest salmon runs have shown some promise, but climate change and human population will continue to stress the river basins.

“Large-scale habitat access projects, such as dam removal on Washington’s Elwha River, have demonstrated that they can promote dramatic abundance and productivity gains, and artificial production and reintroduction tools have proven the potential to reestablish some extirpated stocks,” the report says.

“However, any optimism about future stock status must be tempered by continued pressures from a changing climate and the effects of the ever-expanding human footprint. Rapid, concerted, system-wide actions that expand from existing strongholds are therefore most likely to result in durable biological benefits to interior Columbia stocks.”