You don’t have to attend too many council meetings before you’ll hear commercial fishing described as the world’s oldest profession.

A more land-bound view bestows that distinction on prostitution. An online sage recently suggested this compromise: fishing is the world’s oldest profession, but prostitution is women’s oldest profession.

I’ll leave advancement of that argument to others.

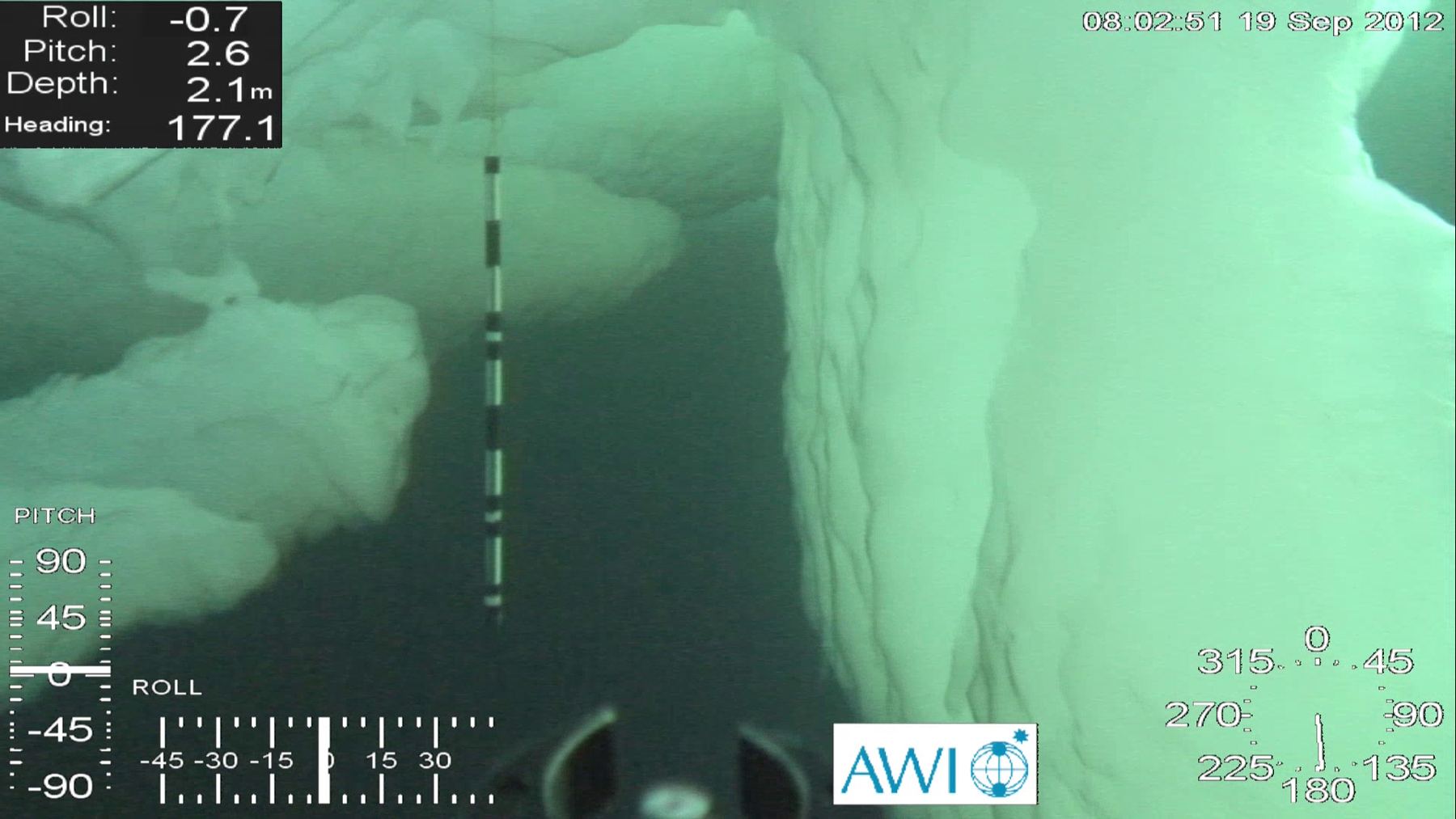

This image was made by a remotely operated vehicle (ROV) and shows the underside of heavily deformed Arctic sea ice. In the center one can see a orientation marker, colored back and white. It is one meter long. Alfred Wegener Institute photo.What I will say is that part of the appeal of fishing is that it is a nexus of old and new. We can say with certainty that it is among the oldest professions. The hooks, nets, and traps we use have existed since the dawn of time and in their elements have changed little since.

And yet we would be out of business without modern technology. It enhances our ability to find and catch fish at the same time it nourishes our understanding of marine life and the ecosystems that support it.

For example, Phys.org reported Tuesday that researchers using what they describe as a surface and under-ice trawl found juvenile polar cod in vast abundance directly under the ice throughout the Eurasian Basin. The thicker the ice, the more fish they caught.

According to the journal Polar Biology, which published the study in August, polar cod, upon which numerous Arctic species depend for sustenance, were known to reside under the ice. What was not known was the extent of juvenile abundance and its correlation with the thickness of the ice. And while the abstract described the fish as in “good condition and well fed,” looming over the report are the consequences of a diminishing ice pack.

All this thanks to a one-off net the size of an automobile designed to float along the bottom of the ice.

Scientists from the Alfred Wegener Institute, the Helmholtz Center for Polar and Marine Research, the University of Hamburg and the Dutch research institute IMARES used satellite data and computer models to determine where to set the trawl.

For a scientist on deck aboard a research icebreaker churning across the Arctic, it is difficult, I should think, to contemplate much beyond the timelessness of the sea and sky before you. Yet the reason you are there, of course, is that there is nothing timeless about the view.