Last week I read an opinion piece in Forbes about the blogger known as the Food Babe (Quackmail: Why You Shouldn't Fall For The Internet's Newest Fool, The Food Babe). Reportedly, the health-food advocate and activist also known as Vani Hari sent Anheuser-Busch InBev scrambling with a demand that the company publish the ingredients for its beer.

Once upon a time, I appreciated the Food Babe’s advocacy for transparency in food production. After all, I like to know what’s in my food. Unfortunately, like many efforts that begin altruistically and with a clear and admirable vision, it seems Hari’s alter ego might have taken a turn toward sensationalism to raise awareness (read: money) for her cause.

What happens next is that the cause gets lost in the noise. Food Babe’s drumbeat to the release of the ingredient list was clearly intended to scare her audience into action. They use plane deicer! Did you know that? What she (and legitimate journalists) failed to report is that propylene glycol is used not to give the beer its je ne sais quoi. It’s used to cool the product and is listed with the ingredients because the law requires manufacturers to list all products used throughout the production process. But it gets even better: Did the Food Babe’s vegan and strict vegetarian followers know that Anheuser uses fish bladders in their beer?! Who would do such a thing? Well the answer is: the Founding Fathers.

According to Forbes contributor Trevor Butterworth, dried fish bladders, called isinglass, have been used to filter beer, wine and liquor for centuries. So the fact that beer makers use isinglass is not news to anyone who knows something about the beer-making industry, it’s certainly not exclusive to big manufacturers and it’s not a process invented to speed product to modern beer drinkers. What has changed in this case is not our beer consumption but our cultural consumption. A single blogger who has developed a good following can create sensationalist news about harmless business practices by renaming a process or product in order to scare consumers.

The real danger, Butterworth says, is when news outlets take the activists’ word for it and don’t get the inside scoop on what they’re reporting. Once you have the complicity of a press corps that is too busy feeding the 24-hour cycle to investigate their stories, then you have easy access to the public. Before you know it, you’ve created the next big Internet rumor. All those reporters had to do was call someone in the industry and ask them about the ingredients listed.

Seafood industry folks should not be surprised by this story. It happens in this business seemingly every day. Big environmental groups that started with a beautiful vision of a healthier, safer planet often get caught up in the never-ending drive for fundraising that requires sensational news to spur their audience to action (whether that be signing petitions, checks or both).

The fishing industry has proved an easy target for these groups, largely because it’s misunderstood or simply unknown to the majority of the American population. We eat seafood, but what we know about it is limited by what we see in the case or on the menu.

But what’s more devastating is when sensationalism gets such a broad audience that it begins to affect policy. That’s what’s happening with (among many other things) the expansion of marine protected areas.

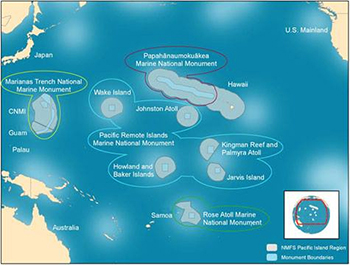

Last week President Obama proposed an expansion of the central Pacific protected area that would create the world’s largest marine sanctuary and double the global area of ocean that is protected. The administration also finalized a rule allowing the public to nominate new marine sanctuaries off of our coasts and in the Great Lakes. His proposal was lauded by people in and out of the know. For those who don’t know much about fishing, it sounds like a no-brainer: The ocean is a big place. Why not earmark just these small parts of it to protect habitat and maintain abundance in the ocean? It’s less than 2 percent of the ocean, after all. And if you call it a sanctuary, well then, who could object without looking like a raving lunatic?

The problem is that while the ocean is a vast place, there are only so many productive fishing spots. You can’t just drop your gear at any random spot in the ocean and pull up a good commercial catch. There’s a reason fishermen haul all the way off to Georges Bank to bring back your supper. They don’t all just love steaming offshore at $4 to $5 a gallon for diesel. They go because that’s where the fish are. There’s also a reason that people in the industry take handed down knowledge and experience very seriously. People who forage the wild will tell you they have their secret spots that are always productive, or tells for locations that ought to be productive. And of course, they take what they need and leave some to keep the spot viable.

This is also how we can and do manage our commercial fisheries. Sure, closing certain areas is part of that process, but we don’t need to close them indefinitely. If we decide to close off all productive habitat to fishing, then soon there will be no more places to go fishing. That is, unless you want to fish recreationally, which is naturally exempted from the area that George W. Bush created and Obama proposes to expand.

But that’s a story for another day.