Article five of a series written by Arni Thomson- History of the Fishing Vessel Owners Association (FVOA), Seattle, WA, Activities from 1914 – 2024.

Prior to the legislation, there were 768 foreign vessels fishing off the coast of Alaska; as of November 1978, the number was reduced to 453. Off the coast of WA, OR and CA, there were 132 foreign fishing vessels operating in 1976, representing seven nations. By 1979, the number had decreased to 40. The total West Coast foreign catch was two million MT in 1976, and in 1978, it was an estimated 1.8 million MT. As Bob noted, the legislation brought about the ability for management where previously there was none in the U.S. Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ).

The bilateral negotiations with Japan and Russia that had been conducted on and off for a decade had failed to bring about any semblance of management of our coastal marine resources. In the case of Pacific Ocean Perch, halibut and black cod and some flounders, the legislation came after foreign fishing interests had severely depleted the resources. The U.S. also gained the authority to place observers on foreign fishing vessels, albeit at only the 10 percent level. Fishermen were confident that the foreign fleets were under-logging their catches resulting in them exceeding their directed fishing allocations and also taking large numbers of halibut, crab and salmon as bycatch in the trawls.

The issues of under-logging catches and the need for observers was addressed in a firmly worded bipartisan letter to Secretary of Commerce, John Byrne from Washington State Senators Gorton and Jackson on September 14th, 1981. They also had the support of Oregon Senators Packwood and Hatfield and Senator Stevens from Alaska. The Senators acknowledged the need for the Department of Commerce to closely monitor foreign nations taking advantage of the nation’s “fish and chips” policy. This was only one example of the Northwest Senators reaching across the aisle to improve benefits for the Northwest fishing industry that also affected some East Coast states.

The bipartisanship began under the leadership of Senator Warren Magnuson from Washington State, joined by Ted Stevens in the early 1970s, and continued for many years. It is very much needed in the U.S. Congress today. The FVOA office archives contain numerous Congressional letters on a myriad of issues the association has dealt with over the decades, and they are a reflection of FVOA’s reputation for sensible recommendations.

Bob also related how there was an ongoing explosion in investment in the fishing industry. There had been an estimated 130 new large vessels designed to fish in the Northeast Pacific offshore fisheries, mostly crab and groundfish vessels.

The cost to build and outfit the vessels averaged two to three million dollars each. Nationally, he estimated there was close to 325 million dollars worth of investment in new vessels.

Bob was also optimistic that with the significant closures to foreign trawling in the Gulf of Alaska and Bering Sea, overfished halibut stocks were beginning to rebuild from a serious ten-year decline from 1965 to 1975, when the harvest plummeted from 63 million pounds to 27 million pounds. In 1978, there had been two years of significant increases of juvenile halibut in the Gulf of Alaska and the Bering Sea. Although the juvenile fish do not enter the setline fishery for another four to seven years, there was reason to be hopeful for the future of rebuilding the fishery. Bernard Skud, Director of the IPHC noted these reductions in a paper he authored, “The 1975 Season.” The IPHC had been imposing successively lower quotas on the North American fleet because of the decline in abundance. The North American fleet was in effect contributing economic benefits to the foreign fleets.

Alverson also pulled no punches in his disdain for the State Department and the Department of Commerce for their reluctance to stand up to foreign nations. In so doing, they exacerbated industry problems. However, he also noted that with the MSFCMA and the new Council system of management, the agencies were no longer a problem. The new system provided ample opportunity for the industry to comment on all management actions and noted that all management actions occurred in front of the public. The passage of the 200-mile legislation mandated a new sense of professionalism from the fishing industry that would only come from participation in the new system. He encouraged his audience to get involved in the process and protect their interests. He also noted the new system was somewhat cumbersome and fraught with legalities and time-consuming procedural delays.

Bob closed with a lesson in the economics and politics of fisheries' joint ventures (JVs) in the North Pacific. JVs result in a U.S. vessel delivering to a foreign processor on the high seas. These processors had “port privileges” in U.S. waters for refueling, taking on provisions and changing out crews---at no cost. Their products though were exported back into the U.S. to compete with more costly U.S. caught and processed product.

Although diplomatic hurdles presented by the “fish and chips” policy were problematic, they were not insurmountable. There was one key ground rule set forth by the 200-mile legislation that proved key to the success of Americanization: If the U.S. fishermen will go out and catch the product, then the foreign nations will be displaced by corresponding amounts.

In this paper, Alverson provides a retrospective on the joint ventures and the mechanics of Magnuson’s “Fish and Chips” policy and the American Fisheries Promotional Act. Foreign nations could receive preferential allocations if they would come forward and buy fish, such as pollock, from U.S. vessels or processors. These legislative acts provided a huge stimulus for the development of the joint ventures and the eventual phase-out of all foreign fishing in the U.S. EEZ. According to Alverson in 1980, the “Fish and Chips” policy did more to set the stage for American expansion in the Northeast Pacific than any other single government action. The policy gave the NPFMC the leverage it needed to force foreign interests to give up their harvesting privileges or risk losing their raw product and market share.

Bob was very active in D.C. on the legislation and at the same time he was chairman of the NPFMC Advisory Panel. Congress asked the NPFMC for their opinion on this matter, and he was able to inform the Council that the AP recommended 100 percent observer coverage on the foreign vessels. The Council Scientific and Statistical Panel recommended that only 20 percent was needed for statistical sampling and that 100 percent coverage would be overly burdensome. Congress gave authority for 100 percent.

Following the collapse of the king crab stocks in 1981, the period 1981-1983 was very difficult for the crab fleet. A lot of vessels went into bankruptcy and were sold for 25 to 30 cents on the dollar at the auction block. The fleet was grossly overcapitalized.

The silver lining, though, was that the vessels being purchased were being converted for joint venture trawling. With new tools provided by the American Fisheries Promotional Act, and with leaders like Clem Tillion and Harold Lokken on the Council, the growth in joint ventures approved by the Council went from 1,500 MT in 1980 for two vessels to 600,000 MT in 1984 for 100 vessels and 18 different partnerships. As Bob noted, there was no turning back, U.S. harvesters were out front, Americanizing the industry and eliminating foreign harvesting. The joint ventures were so successful that boats were being built in U.S. shipyards designed to only participate in joint venture activity,as they had very limited hold capacities. Full cod ends were being transferred at-sea to motherships.

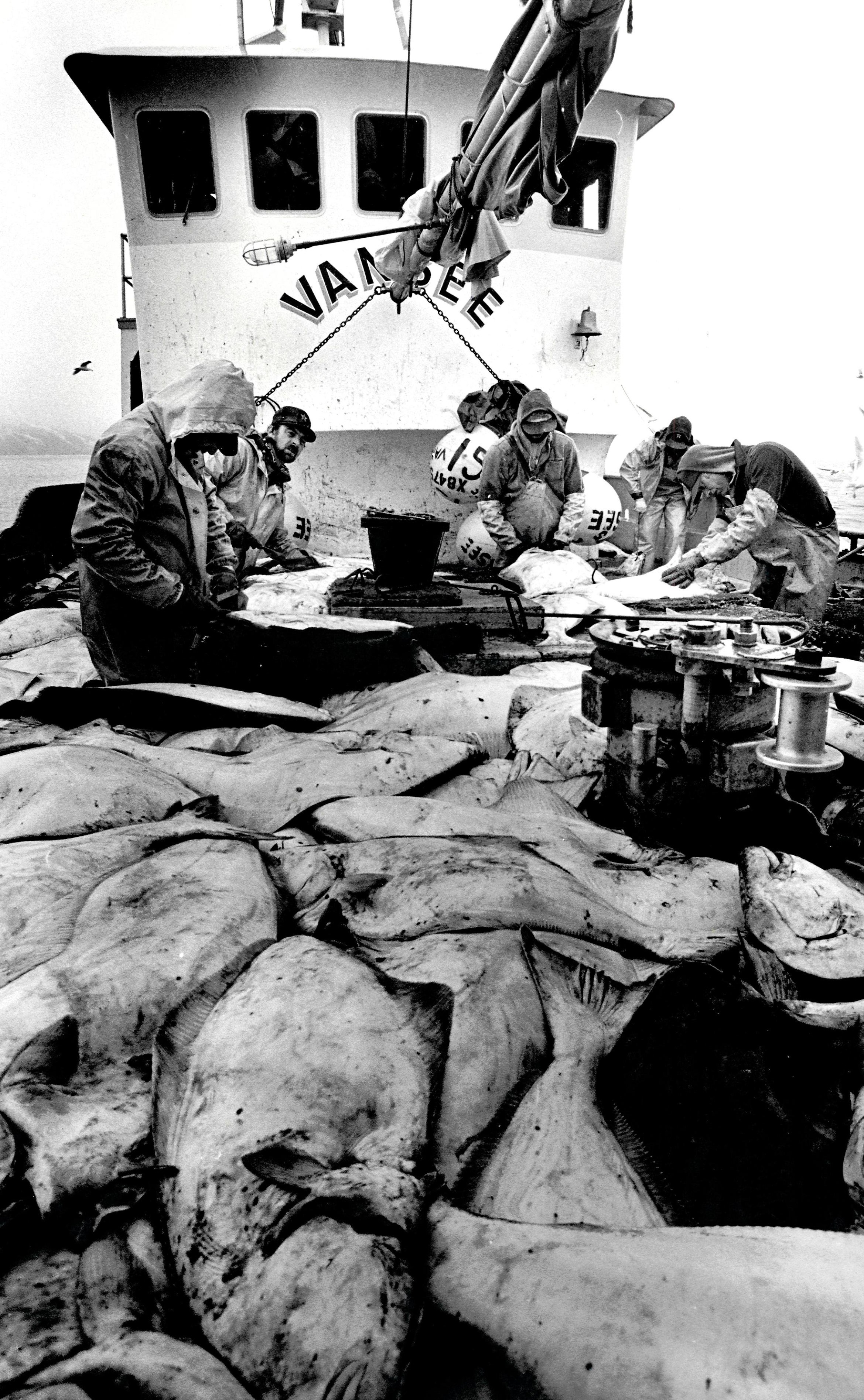

The period 1981-1983 was equally difficult for longliners. The traditional longline fleet was struggling for its existence. The market for halibut had collapsed from $2.32 per pound to 80 cents per pound. However, the resource had fully recovered and boats were bringing in full loads in 3 – 5 days fishing time. In 1986, the Vansee, just one example, had a trip of 125,000 pounds caught in a 48 hour opening in the Gulf of Alaska, one of the largest two day catches in the history of the fishery. One hundred hook skate of gear had 97 fish on it. Resource abundance attracted thousands of new entrants from the salmon fleets. The fishery was hopelessly overcapitalized and the IPHC had invoked derby style openings to prevent massive overages that would impact future stocks.

To make matters worse, the much-anticipated moratorium on new entrants into halibut and sablefish fisheries was declined by OMB in Washington D.C. The other high value species available to longliners, sablefish, was dominated by the Japanese Longline Association with their 22 shelter-decked all-weather 120-foot freezer boats. They also controlled imports into the Japanese market with government-approved quotas. Longliners fought hard at the Council to phase out the Japanese fleet, and in his last year on the Council, Harold Lokken witnessed the season closure of sablefish on September 7, 1984---the quota was caught by the U.S. fleet for the first time. Bob Alverson, as a leading member of the Advisory Panel, also witnessed the historic event.

Conclusions

Adventurous seamen from New England, who travelled 15,000 miles around Cape Horn, who had experienced the depletion of Atlantic halibut stocks, with their sailing schooners and dories, also helped to provide the motivation for preservation of the Pacific halibut stocks. Despite today’s serious downturn in the stocks and historically low quotas at the 30 million pound level for North American fishermen, the industry and the IPHC remain committed to the maintenance of the fishery and hopes for another full recovery.

Clarence Pautzke, former Executive Director of the North Pacific Fisheries Management Council, who began with the Council in 1980 and became Executive Director in 1988 until he moved to the newly established North Pacific Research Board in 2002, recalls Bob’s leadership on major issues quite well.

In closing, Bob credits the generations of FVOA members that have stepped-up when needed, to produce meaningful correspondence, and to testify before the Councils to advance FVOA fisheries issues. Virtually all the members have supported the long-term conservation goals of the halibut and sablefish resources of the West Coast of North America. Throughout Bob’s fifty years of experience in fisheries management forums, fishermen have proven to be the best witnesses on the issues that affect them and the resources.