Opening a can of worms may prove the answer to a salmon fishery researcher's question, especially dead anisakid, roundworms found in old cans of wild Alaska salmon.

Results of the initial study on what four decades of canned salmon reveal about marine food webs were released in the spring of 2024. Now using new grant funds, Natalie Mastick of Arizona State University is again collaborating with Chelsea Wood at the University of Washington to further explore the history of marine parasites to determine the impact on the health of a marine ecosystem.

The current research award from the North Pacific Research Board in Anchorage began in the summer of 2025 and runs through December 2027, Wood said.

According to the Seafood Products Association in Seattle, parasites can reduce the growth, survivorship, and marketability of commercially important marine fish species, particularly in Alaska.

While finding worms in salmon fillets, even dead ones, may cause concern, their presence is not a threat to human health and often signals that the fish originated from a healthy marine ecosystem. High-pressure canning, including the timing and temperatures involved, kills the parasites.

One of her goals in her doctoral dissertation at the University of Washington (UW) School of Aquatic and Fisheries Sciences was to assess how the risk of parasite infections has changed for salmon-eating killer whales in the Northeast Pacific, said Mastick, now the vertebrate collection manager at ASU's Natural History Collections. Wood, an associate professor at UW, was the principal investigator for the studyat UW. It was at her lab that the research team investigated historical changes in parasite abundance using museum fish specimens.

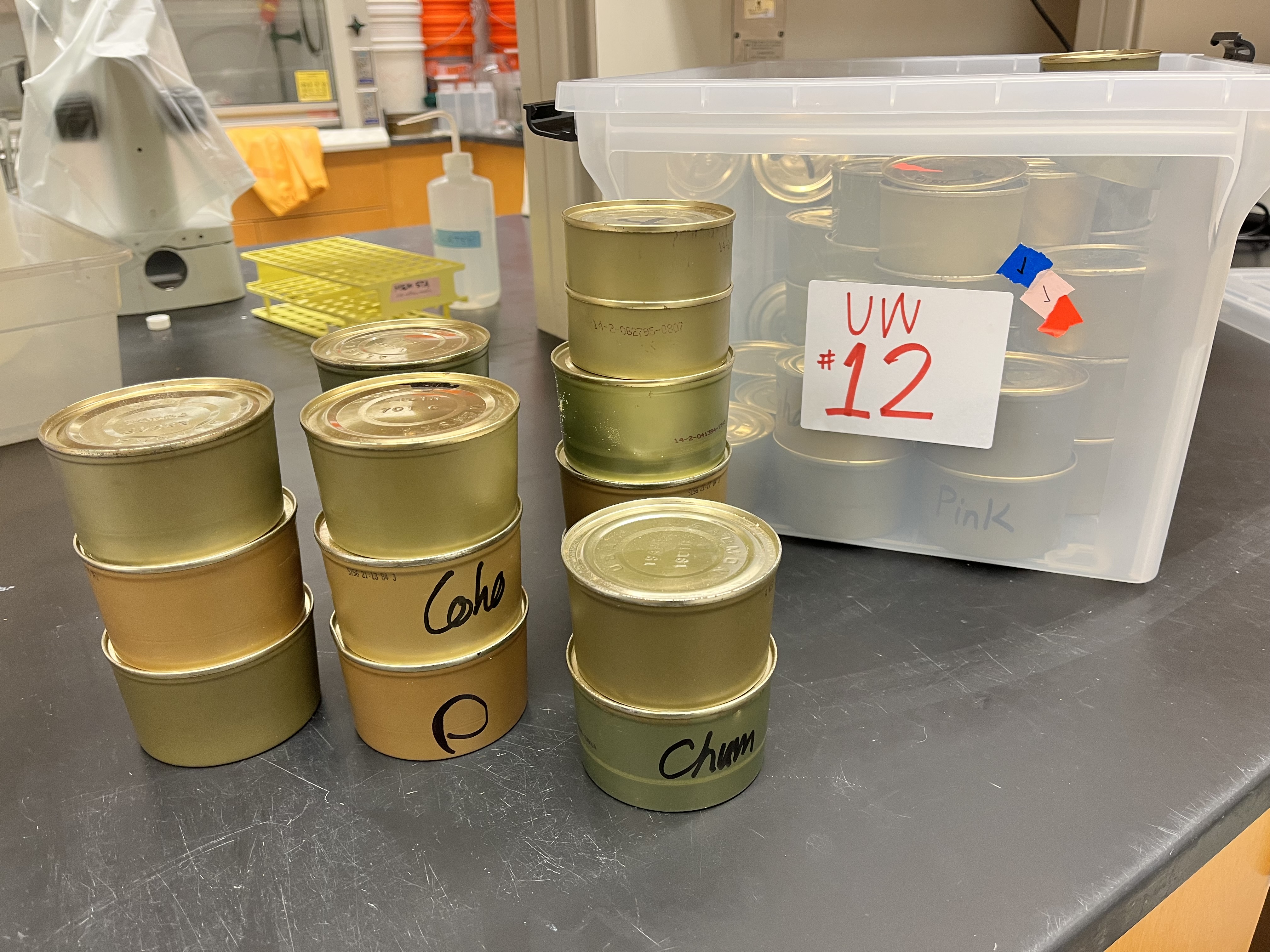

The problem was that museums rarely retain adult salmon because they are large and have high commercial value, Mastick said. Then the Seafood Products Association offered them cans of salmon dating back to the 1970s. "We decided that it was worth a try to see if we could find parasites in these cans, even though they were cooked and some had clearly gone past their shelf life," she said.

The 178 cans contained fillets of sockeye, chum, pink, and coho salmon, with tiny dead anisakid roundworms in the flesh. Their presence during the years that the salmon was canned was a signal that they came from a healthy ecosystem, Wood said. Their research paper reported that anisakid worm levels rose for chum and pink salmon from 1979 to 2021, while remaining unchanged for coho and sockeye.

Chinook salmon was not included because cans of the kings were unavailable.

Seeing parasite numbers rise over time indicates these parasites were able to find the right hosts and reproduce, suggesting a stable or recovering ecosystem with enough of the right hosts for anisakids, Mastick said. Researchers are unsure whether these worms are more likely to infect certain kinds of salmon. They saw differences in infection rates across the different species, with sockeye being the most infected, but couldn't determine why there were these differences, she said. Wood's lab is still researching historical changes in parasite abundance, but has no active studies using canned products, Mastick said.

Anisakids are unlikely to infect farmed salmon because farmed salmon are often fed processed food and have less exposure to anisakid infections.

Mastick said she has considered researching other fish species using the same methods. The issue is finding a dataset comparable to the one that the Seafood Products Association donated for the initial study. Still, it is definitely possible that anisakids could be detected in other wild seafood products. "Anisakids are a very diverse family of nematodes (roundworms) and can infect a lot of different host species," she said.

"They also have different life cycles and can be found in different areas of the ocean depending on the species," she said. "It is possible they'd be detected in fish across the food web, from anchovies and herring to larger fish like tuna and halibut."

If a large enough trove of cans of other species were available, such research would be absolutely useful for assessing changes in parasite infection over time, according to Mastick. "These types of studies provide some support for what fisheries are anecdotally seeing and help quantify these trends over time," she said.

To date, these parasite research results have been published in online research journals and presented at domestic and international conferences, as well as on public broadcasting networks.