A draft environmental impact statement for the South Fork Wind Farm project off southern New England includes alternatives for a fishing vessel traffic lane and protecting ocean bottom habitat for fisheries.

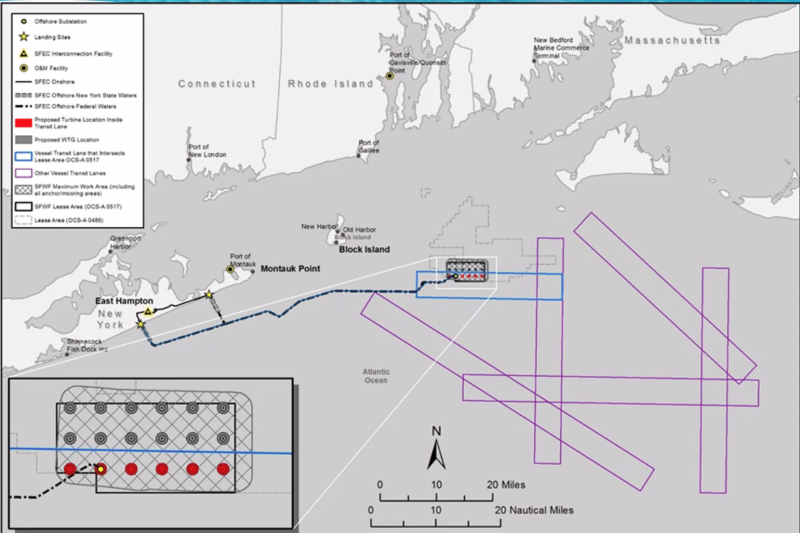

Both could potentially displace preferred locations for up to 15 wind turbines of 6 to 12 megawatt capacity planned by project partners Ørsted and Eversource. The federal Bureau of Offshore Energy Management is considering the companies’ construction and operations plan for the project 19 miles southeast of Block Island, R.I., and 35 miles east of Montauk, N.Y.

The developers propose to lay out the array with one nautical mile spacing between turbine towers, consistent with plans for adjacent wind power developments south of Rhode Island and Massachusetts.

A series of three virtual public hearings online followed BOEM’s January release of the draft environmental statement. The last proceeding Feb. 16 attracted project supporters from New York State labor, industry and environmental groups, and skeptics of its potential effects on the region’s fisheries, which the impact statement broadly summarizes as “negligible to moderate.”

Agency officials say they anticipate publishing a final version of the impact statement in August 2021, followed by a record of decision in October that could clear the way toward construction.

The rectangular South Fork lease area is one of the smaller projects planned between Long Island and Martha’s Vineyard, Mass. The proposed array and its subsea cable routes are drawing objections over how they may affect seaside communities and fishermen’s ability to work across the entire area. Supporters portray it as a boost to New York’s technology and construction industries and energy for eastern Long Island.

“It’s not on their backyard, it’s off Rhode Island, not New York,” said Meghan Lapp, fisheries liaison for squid processor Seafreeze Ltd. In North Kingston, R.I. Squid fishing in the area planned for the South Fork project “will be impossible if it goes off as planned,” she said.

BOEM needs to develop a cumulative impact study for South Fork, as it did for the much larger Vineyard Wind plan, said Lapp. The extent of the project’s proposed transmission cables with sections protected by rock emplacements would be another hazard for fishing, she said, as squid vessels “can’t fish on top of cable armoring because it will destroy their gear.”

The BOEM draft environmental impact statement includes two alternative design frameworks. One, incorporating a vessel traffic lane proposed in January 2020 by the fishing advocacy group Responsible Offshore Development Alliance, could eliminate one row of turbine sites on the south side of the lease.

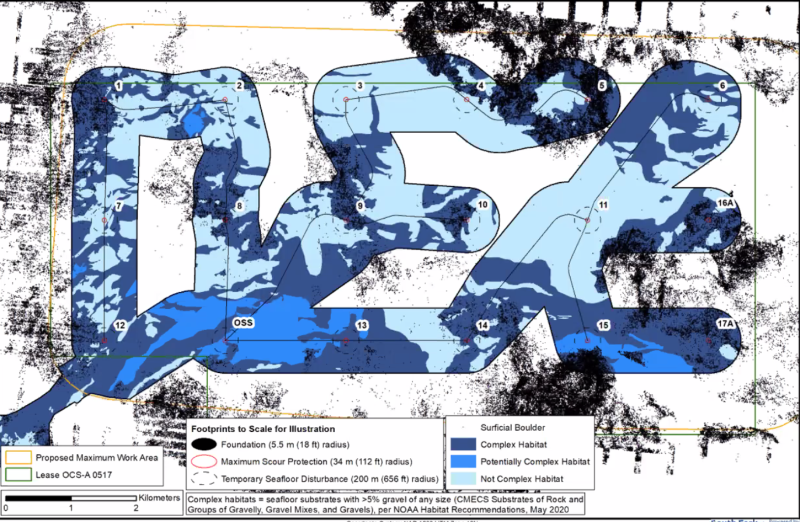

The second, dubbed the “Fisheries Habitat Impact Minimization alternative,” would have BOEM require the developers to change some turbine and cable locations, moving them away from bottom types that are important habitat for fish.

The BOEM document notes that alternative could lead the agency to approve fewer turbine locations – but also that it would be “still within the proposed design envelope of up to 15 turbines and the 6- to 12-MW range.”

The only easing of the plan’s impact to commercial fishing could be using the alternative for a vessel transit lane, said Bonnie Brady, executive director of the Long Island Commercial Fishing Association.

The environmental impact document is “at the same time both rushed and outdated,” said Brady. It has no reference to a Department of Interior legal memorandum – issued in the waning weeks of the Trump administration – that stressed the department’s obligation to consider effects on fishermen, she said.

Already occasional conflicts between fishermen and project survey vessels are an issue around Montauk. There is no clear process for fishermen to make claims for gear loss, and BOEM’s plan needs to consider both compensation and mitigation, said Julie Evans of the East Hampton Town Fisheries Advisory Committee.

“There’s a lot more work to be done here,” said Evans. I don’t think people dislike fishermen. If you like to eat seafood, you might want to spend a little more time on this.”