It’s a common phenomenon when reviewing statistics: Humans tend to focus on the numbers, forgetting that they often represent human lives.

Today, a National Transportation Safety Board hearing comprising two panels of industry experts seemed to hammer home the point that fishing vessel safety improves by leaps and bounds when it’s geared specifically toward improving safety on commercial fishing vessels, when it’s done face to face, and with the specific fishermen’s needs at the forefront.

You might be asking: Isn’t any safety effort applied to the industry designed to save fishermen’s lives and therefore putting the fishermen’s needs first?

And my answer is: Yes and no.

In the last two decades, there’s been a major overhaul in safety practices among U.S. commercial fishing fleets, thanks to three major changes — accessible technology, fishing-specific approaches to safety, and acceptance among the fleet. The last one, today’s discussion showed, comes as a result of the first two.

The panels discussed vessel stability, crew training, safety equipment (both personal and vessel specific), dockside exams, and the evergreen problem of drug use among crew.

The responses ranged from calls for more regulation and enforcement to changes in fishing safety culture that improve relationships between regulators or researchers and commercial fishermen.

“Contact, communication and collaboration” are the key ingredients, according to Jerry Dzugan, executive director of the Alaska Marine Safety Education Association in Sitka.

Without an exception, the safety efforts that have resulted in significant changes in fishing safety culture involved walking the docks, talking to fishermen, and a desire to act on that feedback for the good of the fleet.

“Get your boots dirty,” said Jennifer Lincoln of the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. “We pride ourselves on making our work relevant to the industry and all recommendations actionable. Research findings and technologies have been transferred into practice. I am sincerely excited about always seeing a deckhand and a lifejacket or an emergency stop switch in the wild on a fishing vessel.”

Chris Woodley, executive director of the Groundfish Forum, noted that when he was performing dockside exams in the Coast Guard, they joked that they were vacuum cleaner salesmen, walking boat to boat and dock to dock to get in the face time necessary to become familiar to the fleet.

“Collaboration has to be the starting point. I think you need great communications between the industry and between the regulators,” Woodley said. “The thing is, when people see the Coast Guard out there and interacting with their friends and buddies on other boats, I can tell you 99 times out of 100 the person watching the interaction is going to say, you know what? I'm going to go talk to those guys for a second.”

Oftentimes, it’s fishermen who have helped the safety sector find a way in.

“I remember a specific fishing vessel advisory committee meeting way back when when there was a fisherman named Jimmy Ruhle who said: ‘Why doesn't somebody give us some lifejackets and ask us what we think about them?’ That was the start of the first lifejackets study we conducted with commercial fishermen in Alaska,” Lincoln said.

“We distributed lifejackets to 400 fishermen throughout the state operating in different fisheries to identify lifejackets that work, lifejackets that overcome their entanglement hazard concerns as well as comfort and wearability concerns,” Lincoln added. “That study has been repeated in other locations.”

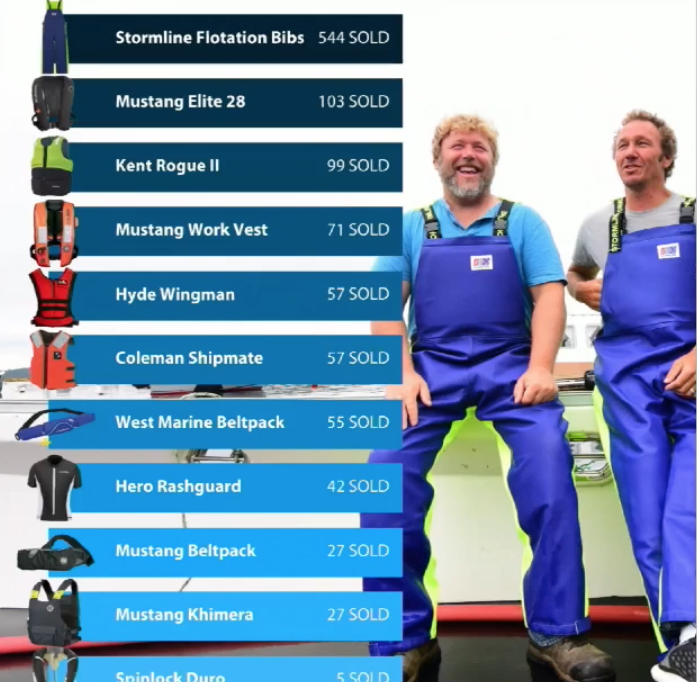

It also led to a regional collaboration that became the Lifejackets for Lobstermen program, headed up by Julie Sorensen, director of the Northeast Center for Occupational Health and Safety.

“I think one of the things I learned from this program is that fishermen, particularly lobster fishermen, were very invested in finding a solution. I was I guess a little surprised and impressed that they were so eager to work with us to find a solution,” Sorensen said. “We went to commercial Marine suppliers, where fishermen shop. What we found is that there were one or two dusty lifejackets in the corner it was quite apparent nobody had looked to in a while. When we talked to suppliers back then, they said, well, fishermen don't come in here looking for lifejackets. So it was kind of a chicken and egg situation.”

The lifejackets program has distributed more than 1,200 PFDs to Northeast lobstermen at half the retail cost.

And it’s already helped some fishermen come back home.

“Two of the fishermen who participated in the project had a fall overboard and survived,” Sorensen noted.

The Alaska Marine Safety Education Association documented its effect on industry safety after four decades of training fishermen all over the country.

“Of those 24,000 people that have been trained, we know of over 350 that have survived an emergency at sea,” said Jerry Dzugan. And those were just the people AMSEA knew about.

“So we decided just to take a sample of that group of 24,000 people and contact them to see if they were helped by training in the last five years,” Dzugan said.

What they found was that more than 30 percent of the people they contacted had used their training in the last five years to handle or prevent an emergency.

“Ninety-one percent of those fishermen said when asked if they changed their safety practices as a result of the training responded affirmatively that they did,” Dzugan added.

Changes like this come with a price tag and efforts to go where the fishermen are, he noted.

“We traveled to 240 different ports around the country making those classes accessible to fishermen. That is expensive,” Dzugan said. “By its very nature, fishermen work out of and live in remote ports. In Alaska alone, going to Dutch Harbor is the same amount as going to Europe, for example.”

The key, regulators seem to understand now, is making rules that can be tailored to the fleets.

“What I do see going on a lot of times is folks that make the regulations will not work with the industry to make it work for everybody,” said John Williams of the Southern Shrimp Alliance.

On the topic of alternate compliance following the 2010 U.S. Coast Guard Authorization Act, Woodley explained why some of the regulatory efforts ended up falling flat.

“Unfortunately, when it comes to trying to take all the fishing vessels in the country and trying to figure out all the regional and fleet specific differences on a fleet by fleet basis in a very systematic way, frankly, the Coast Guard is not set up for that,” Woodley said. “The Coast Guard does a lot of things well. I think when it comes to carving out or identifying specific understanding for specific fleets, and being able to implement that in a regulatory way, that is a really tall order.”

Even when it comes to trying to solve the problem of drug use onboard, the answers came down to differences in fleet size, amenities, fishery and ownership.

“From our fleet's perspective, the larger boats that fish on the Bering Sea that are all over 200 gross tons, they all have drug testing programs and are required by law to do that,” Woodley said. “And it does limit the number of people that are on board. If you fail a drug test, you are gone. That is the consequence. You are likely going to lose your job.”

“That is a solution that is really a challenge to implement on a smaller boat fleet,” Woodley added. “It is a societal problem. It is not a fishing industry problem in and of itself.”

Sorensen, who works primarily with a coastal and small-boat fleet in New England, agreed that the answer will not be as simple as drug testing, because crew shortages are part of the problem, too.

“I think what we need to do is look at the root cause. If you look at many of the people working in this industry, the physical labor is such that people develop injuries over time that make it very difficult to work without pain. So they take painkillers. Painkillers are a gateway drug. If you can't schedule an appointment with your provider to get a new prescription, you might just take whatever is available dockside, which may be something you can get from a drug dealer.”

“I think the best way to start is to try to find a program that helps fishermen treat their pain in a way that doesn't lead them to addiction and provides resources that are really tailored to the industry,” Sorensen added. “Fishing Partnership is a great example of that. They developed a program where they have recovery coaches and Narcan training for fishing boat captains.”

Maybe one day we’ll be able to solve our cultural drug problem the same way we’re improving fishing vessel safety — by working directly with the people to address the problems on the ground before they become problems on the water.

“The key is really making engagement of the fishing industry a priority and understanding with those issues are,” Lincoln said. “I don't think that can be emphasized enough — that the dockside examiners and part of the Coast Guard that works directly with fishermen have a huge role in improving safety. Whether we are talking about specific things that are in regulation or specific things that just should be done because it is good mariner practice. So dockside examinations, just walking the docks, interacting with fishermen, and the same goes for any research or other that wants to work with commercial fishermen.”