Reading BOEM’s proposed guidance to wind developers

The federal Bureau of Offshore Energy Management is looking for fishermen’s comments until Aug. 22 on the agency’s latest ideas on how wind energy companies might mitigate the impacts from building offshore turbine arrays.

On June 23 BOEM released its draft guidance documents presenting the agency's thinking on ensuring the new U.S. offshore wind industry can work with the nation’s long-established commercial and recreational fishing industries.

The guidance document focuses on four areas:

- Project siting, design, navigation, and access

- Safety

- Environmental monitoring

- Financial compensation

BOEM began soliciting input on mitigation policies in November 2021. That first call brought in 92 comments from individuals, state agencies, wind energy companies and, of course, fishing trade groups and associations.

In the ensuing draft document, financial compensation gets the most attention. Many fishermen, especially those who fish with towed mobile gear like trawl nets and dredges, insist they will be effectively shut out of areas after turbines are erected.

Just how big those future losses may be developed within a separate ‘Appendix A’ in the document that presents BOEM’s ideas for calculating “revenue exposure estimates. Such calculations could determine fair payments to fishermen because of income lost to wind projects.

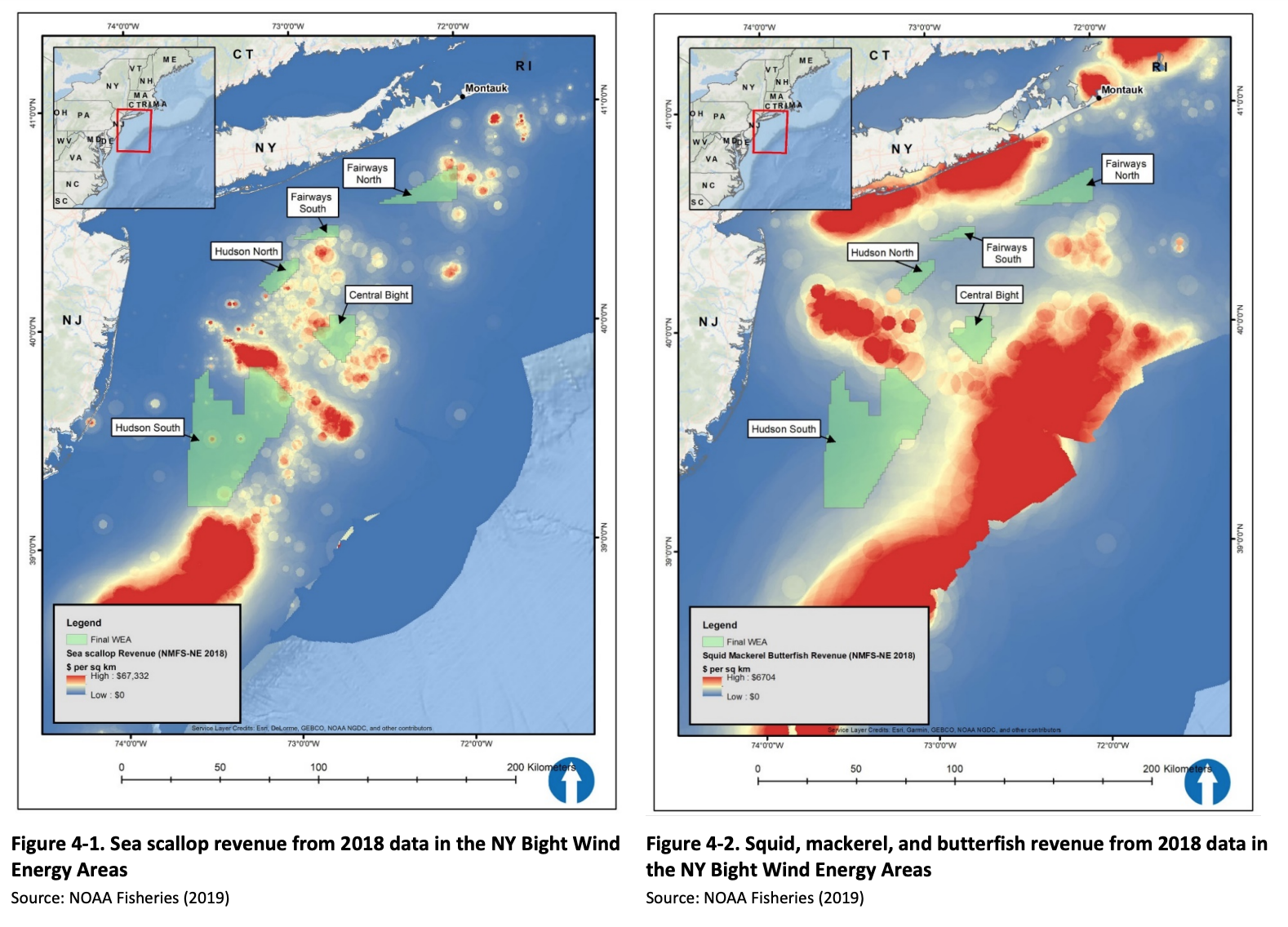

Estimating fishing effort, catches and value that come from wind lease areas has been intensely debated for years. BOEM’s earliest attempts using federal and state landings reports were hotly disputed by fishing advocates, who collected vessel tracking records to show where proposed wind development sites included heavily used fishing areas.

Since then, BOEM has worked closely with the National Marine Fisheries Service to develop better systems, mapping out the most intensely used and valuable fishing grounds.

The mitigation strategy methodology is built around using federal fisheries catch and revenue data as a starting point. NMFS and its Northeast regional office are the primary source for revenue calculations in that region. The first U.S. wind projects are to be built there, and mitigation measures could be adapted to fisheries on the Southeast, Gulf of Mexico and Pacific coasts.

Appendix A includes a table called "Derived Fishery Revenue Exposure Products." The Table includes links to federal databases from NMFS and BOEM, as well as more straightforward documents. One is the January 2019 report prepared for the 800-megawatt Vineyard Wind project off southern New England, titled “Economic Exposure of Rhode Island Commercial Fisheries to the Vineyard Wind Project.”

Using the table, companies would develop potential revenue exposure. One reference, for example, is a link to NOAA's "Fishing Footprints" site for calculating revenue or "pounds landed" data, for about 75 species, from 1996 to 2018. Yearly totals are provided and there are also filters for "species," "gear," and fishery management plans.

BOEM lists 13 species and specie groups – for example, Atlantic herring, monkfish, and multispecies small mesh. The agency believes there is a "high degree of confidence" in revenue estimates based on Fishing Footprints.

For the non-specialist, information at these sites is not always straightforward.

For example, a Fishing Footprints map for haddock in 2015 presents a dollar number: $837,000. But that sum isn’t within any context. In an email, NOAA was asked for clarification and staff explained that the amount references the highest dollar value within a certain ocean area, in this case a 500-meter square, part of an analytical grid.

In fact, NOAA suggested another site for revenue information. Interestingly, that alternate site is not within Table 1 in Appendix A. The point is, fishermen will want to make sure that revenue decisions are based on clear and transparent methods, within an apples-to-apples context.

Things get more complicated with "data-limited commercial fisheries" and species for which "there are substantial limitations" to revenue exposure data, including American lobster, Jonah crab and highly migratory species like tuna and swordfish.

For these figures, BOEM suggests using a worksheet type of format, pulling information from various sources. It also suggests that energy companies prepare exposure estimates for shoreside seafood businesses, such as bait suppliers and seafood dealers and processors.

Additionally, BOEM suggests that wind energy companies review data from vessel monitoring systems (VMS), required by permit holders fishing in federal areas. BOEM writes that VMS data can help a company understand "finer scale" vessel activity and variations and routes to fishing locations. BOEM cautions, however, that VMS data is not always straightforward and has limitations.

The draft does not include how someone might file for payment, and what kind of documents would be required to complete such a filing. Again, this draft is meant for wind energy companies, not individual fishermen.

Keep in mind that the mitigation measures are suggested measures – not directives to wind developer. Mitigation measures must be included in a company’s Site Assessment Plan or its Construction and Operations Plan. These could follow BOEM’s Guidelines, or the company could present different ideas.

Here's a brief look at the other BMP topics:

Project siting, design, navigation and access

BOEM suggests early interactions between energy companies and fishermen. BOEM writes that no “standard facility design will mitigate potential impacts to all fisheries in all regions.”

But BOEM does suggest that certain design elements should be on a company’s short list. These include:

- Burying all static cables on the sea floor to a minimum depth of 6 feet below the seabed “where technically feasible.”

- Establishing cable protection measures that are “trawl-friendly” and avoid new obstructions for mobile fishing gear.

- Suspending “dynamic cables” that hang in the water column at depths that minimize effect on fishing operations.

- Where feasible, cables should be set in common corridors to minimize “cable footprint.”

- Using larger turbines to reduce the total project site while still meeting energy requirements.

Safety measures

BOEM recommends ten mitigation strategies. Examples include:

- Charting all work and sending that information to be used in navigation software;

- Using digital information technology platforms to provide notice of project schedules; and,

- Providing simulator training to teach safe navigation through a wind facility.

The Safety section makes only brief reference to the National Academy of Sciences’ report last February about how wind energy towers disrupt marine vessel radar. The draft document suggests monitoring radar disruption and that companies should consider paying to equip fishermen with upgraded radar systems to operate safely near turbine arrays.

This low-key reference contrasts with far more pointed public concerns from fishermen.

The Fisheries Survival Fund, a group of East Coast sea scallop fishermen, told BOEM that if steps can be taken to better ensure vessel radar systems, “these steps need to be identified, tested, proven, and specified in processes that include fishermen.”

Responding the BOEM’s request for comments on navigation issues, New York State officials suggested waiting on safety guidelines until the NAS radar study was completed. One fisherman wrote: “Radar systems are pretty much useless inside a wind farm. Come up with a new system that shows targets in relation to your vessel and I will withdraw my comment.”

Environmental monitoring

This topic area references a longer and more subjective set of requirements and tasks to document changes to fisheries and other environmental conditions from offshore wind development.

BOEM recommends two sources for baseline studies. One is a BOEM “Survey Guidelines” website addressing site characterization, avian information, archaeological and historic properties and, of course, fisheries information.

The second is to recent work in 2021 led by the fishing industry-supported Responsible Offshore Science Alliance, prepared in conjunction with government fishery officials. BOEM refers to this document as “an important resource in understanding necessary considerations in developing pre-construction, construction, and post-construction fisheries monitoring surveys.”

Next steps: Hardball or softball?

One concern with guidelines is their informal regulatory status. Fishing advocates are pressing BOEM to set enforceable terms and conditions within wind companies’ future operating permits.

This perspective is made very clear in comments from the Responsible Offshore Development Alliance. RODA is a coalition of more than 200 fishery-dependent companies, associations, and community members that has been a foremost voice in bringing their concerns to BOEM and the wind industry.

RODA insists that BOEM has authority to “impose any necessary permit conditions” under federal law to safeguard environmental standards. Moreover, the group notes that developers are already deviating from BOEM’s established communication guidelines and that wind developers “have publicly acknowledged their interest in regularly employing variances from guidelines.”

New York State agencies from the governor’s office on down are totally committed to developing offshore wind energy. Yet state officials have acknowledged the concerns of RODA and New York fishermen, to “recommend BOEM consider all regulatory pathways” including “Congressional action to pursue a legislative solution to standardize and mandate conformance.”

BOEM’s public comment period is open until August 22.

Tom Ewing is a freelance writer focusing on energy, environment and related regulatory issues.