Electricity from the Equinor and BP Empire Wind project should start coming into New York’s power grid in 2025, according to updated plans the joint venture has filed with the federal Bureau of Ocean Energy Management.

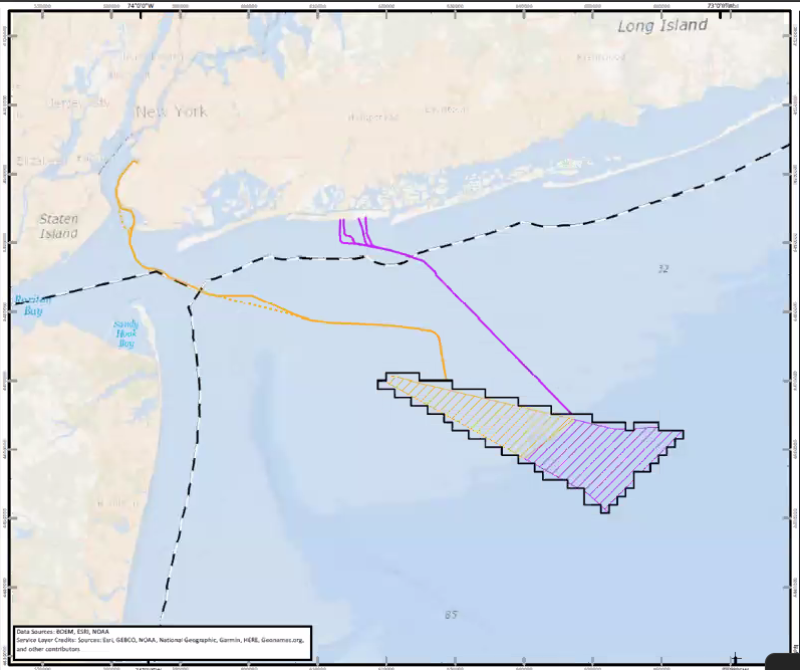

The first offshore wind energy project laid out for the New York Bight is a 79,350-acre tract, shaped like a slice of pizza wedged between two of the ship traffic separation lanes in the New York Harbor approaches.

With the enormous volume of vessel traffic in the region – container vessels at the port of New York and New Jersey, coastwise tug and barge tows, plus commercial and recreational fishing fleets – navigation has been the foremost issue since New York state energy planners first began looking to ocean wind as a power source.

“There is certainly a concern about setback” from the shipping traffic lanes, said Lucas Feinberg, a project manager with BOEM, during a July 8 online virtual public scoping session hosted by the agency.

Early on, planners agreed to a 1-nautical mile setback along the Empire Wind frontage along the shipping lanes. Formally known on charts as traffic separation schemes, the lanes fan out from the New York Harbor entrance at Ambrose Light.

BOEM’s original federal energy lease offering in June 2016 was for 81,130 acres at the New York Bight apex. But the northwest tip of that tract was shaved off at the recommendation of fishermen and the National Marine Fisheries Service, to exclude the Cholera Banks – a prized fishing ground, named for its use as a quarantine station for immigrant passenger ships in the early 1900s.

Equinor, then known under its old name of Statoil, was the lease auction winner among six other developer with a bid of $42.47 million, later bringing in BP as a partner.

Plans now call for building the project in two phases: The westernmost section with 816 megawatts potential power, and a second phase of 1,260 MW.

Rising from the water 14 miles south of Long Beach, N.Y., and 19.5 miles east of Long Branch, N.J., the turbine towers as now planned would be laid out with at least 0.7 nautical mile separation and orientation to allow vessel transits on southeast to northwest passages, said Laura Morales, Empire Wind’s permits manager.

Those plans won’t work for the mid-Atlantic sea clam fleet, said David Wallace, a longtime advocate for surf clam and ocean quahog fishermen and processers.

“The clam industry is unique in that its directed fishery” is on sandy and muddy sea floor without heavy rock formations – the outer continental shelf attractive to wind developers, said Wallace. That means clam fishermen “will be negatively impacted by…the thousands of wind industry turbines” that could be built, said Wallace.

Clammers have advocated 2-nautical mile separation between turbines that would give them more room to maneuver their heavy hydraulic dredges between turbine arrays and power cables.

“We are not interested in being collateral damage” from wind development, said Wallace. “If there are no marginal areas to fish, we go out of business.”

Alternatively, government and developers could provide assistance to the industry, Wallace added, with dedicated funding assessed on a per-megawatt basis to pay reimbursement for gear damage and loss of fishing grounds.

Other commentors in the event stressed the need to develop renewable energy for New York and Long Island in particular. Tom Barracca, a longtime energy professional on the island, recalled working on an original 2002 study of offshore wind for the Long Island Power Authority, “although the offshore wind technology wasn’t there 20 years ago.”

Today, LIPA is looking to rely on renewable sources for 70 percent of its power by 2030 with a goal of 100 percent by 2040. The authority must figure out how it will retire natural gas- and oil-fired generators in the region, go without nuclear energy with New York’s Indian Point reactor closing – all while building battery storage and anticipating long-term conversion of homes to heat pumps.