Gillnetting off the Outer Banks, sometimes just getting home is a good day.

Like the Apollo 13 astronauts who set out for the moon in 1970 and found themselves trying to get home alive, captain Tommy Danchise and his crewman, Robert Boyd, set out to catch Spanish mackerel off North Carolina’s Outer Banks, not expecting to spend the day on anchor trying to get their fuel-starved engine running.

The 430-hp 6CT Cummins had roared to life at 5 a.m. on a hot August morning as it had hundreds of times before. “We didn’t go yesterday, but we got fuel and ice,” says Boyd, pointing to two big plastic tubs just aft of the wheelhouse.

Danchise and Boyd are usually happy to fill one of the tubs with a thousand pounds of fish, Boyd explains. “But when the water is 80 degrees and the air is 100, you have to ice heavy, so we bring plenty.”

Boyd and Danchise are both in their early 70s and have been fishing all their lives. They wear shorts and light shirts, Boyd with flip-flops, and Danchise with a pair of short deck boots.

Danchise backs the 46-foot boat out from the dock and starts heading down the length of the harbor in Wanchese, N.C., steaming south toward the notorious Oregon Inlet, a site of many shipwrecks, including one of Danchise’s boats.

“I was trying to tow a trawl boat through the inlet,” says Danchise, who is regarded by many as the unofficial pilot of the inlet. “They told me they had untied the line, and I put the throttle down to get away from the bar, but they hadn’t untied it, and when I came on to it, the line came tight and rolled us right over. We were in the water hanging on to the boat.”

Danchise threads along the narrow channel, only 9 feet deep in many spots, but the Landon Blake only draws 3.5 feet. “It used to only draw 2.8 or something,” he says. “But we put a bigger wheel on, and that brought her down.” The boat is narrow, about 12 feet at its widest, according to Danchise. The Cummins has a Twin Disc gear at 2:1 turning a 26x26 propeller, and it moves them along. They pass under the Hatteras bridge, accompanied by a long parade of multi-million-dollar sport boats. For recreational charter anglers, “it costs $2,500 to go out on one of those,” says Danchise.

“Three thousand, by the time you include the tip and all that,” says Boyd. But the big-boat skippers are polite, letting Danchise know when they pass on the port or starboard. And as the sky lightens in the east, Danchise opens the throttle and heads south at 14 knots, making his way past familiar landmarks like a pair of beachfront houses now standing on pilings in the surf, abandoned and waiting for the sea to take them.

“There were five there last year,” says Danchise, pointing. “Now there’s only those two.”

“That’s the boiler,” he says, pointing offshore to a big iron boiler sticking up above the surface. “One of those paddle boats was coming by here in 1862. It ran aground there, and that boiler’s been sticking up for a hundred and sixty years – through all the hurricanes.” Hurricane Erin is the latest, just churning now far away.

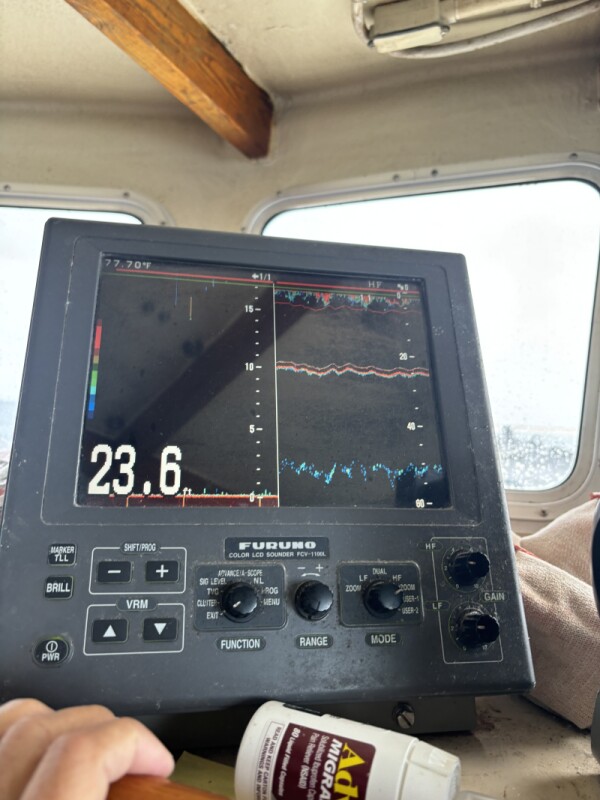

Steaming along just a quarter to a half mile offshore, Danchise has a Furuno FCV-1100L sounder that he watches looking for a sign of bait fish. “Where there’s bait, there’s fish,” he says. He also scans the surface looking for birds. Boyd stays on deck. “Easier to see birds,” he says.

He spots a few, but Danchise gives them a pass. “I’d have liked to give those birds a try, but they was right in the wash,” he says. “And with this southeast wind, it could push us in.”

Danchise spots a big sign of bait on the sounder, and they decide to set. Danchise runs in as close to shore as he can, and Boyd, at the stern, tosses a black buoy and starts to roll the net off the freewheeling drum, braking it with his hand on the flange. “The nets are about 400 yards long,” he says. “Depending on how much we’ve had to take out. It’s 3 ¼ mesh, about 20 feet deep. It’ll go to bottom.”

Danchise turns and puts a curve in the end of the net as Boyd clips a white buoy to it and tosses it over the transom.

“That drum is homemade,” Danchise says of the lower drum. “The other one is a Kinematic, from Washington.”

They set another net the same way and then head back to the first to haul it. Over the radio, another fisherman says he got 250 pounds out of one net, a good haul, and hopes are high. From a steering station on the rail, Danchise bears down on the black buoy. Boyd gaffs it, clips it to the reel, and they begin to haul in the net.

They have donned white oil gear and begin picking the net, shaking a few small bluefish, the occasional Spanish mackerel, a couple of threadfin herring, sand sharks, and two black tip sharks out of the meshes. The sand sharks and threadfin go over the side, the rest into a basket.

It’s a meager haul compared to what they hoped, and the second net is worse, but that becomes the least of their problems when the engine chokes and dies. Having had some problems with his Racor filter the week before, Danchise assumes that’s the issue again. “There’s a little ball that seats in there, and if you get something in there, it won’t seal,” he says.

In a scene most fishermen have experienced, Danchise and Boyd break out the toolbox and lift off the engine cover. They start to work their way back through the fuel system. Boyd drains the Racor into a jug and takes it apart. He hands the bottom section to Danchise. “There you go,” says Danchise, pulling a black glob from around the steel ball he’d mentioned. “It had a bugger in there.”

Assuming they have the problem solved, Boyd puts the Racor back together and pours the fuel back in. They put the hatch cover back, and Danchise starts the engine, ready to make another set.

But it’s not to be. The engine dies again after as long as it takes to burn the fuel out of the Racor. The east wind is blowing the boat towards shore. “Get the anchor out,” Danchise says to Boyd. They toss the anchor, keeping the boat safely offshore while they dig into what is obviously a bigger issue. Danchise directs Boyd, who turns the wrenches. “Try taking that line off,” he says. “Fill it with fuel and put it back.” After Boyd completes the operation, Danchise starts the engine, but again, it dies. The voices of other fishermen offering advice crackle over the radio as Danchose and Boyd chase the problem all the way back to the tank.

“There’s no fuel getting out of the tank,” says Danchise, so they decide to rig a line direct from the tank to the engine. But they need a longer fuel line. They try to connect the two lines they have, but there is one fitting the wrong size. Another fisherman on a nearby boat has some fittings. “I’ll put them in a bag and throw them over to you,” he says over the radio.

Stern to stern, he tosses the fittings over and by luck Boyd finds what he needs to make the connection. Danchise puts the end of the line into the tank and again, by luck, it’s just long enough. He starts the engine. It runs and keeps running! At last, they hoist anchor and start for home with the jury-rigged fuel line feeding the Cummins.

“I hate to be towed,” says Danchise, as he pushes the throttle forward to see how fast he can go on with the improvised fuel line. “I think we can run like always,” he says, pushing the boat to more than 13 knots.

Boyd puts the tools away and cleans the diesel and grease from his hands. He finds a seat on top of a fish box and watches the wake spread behind them.

An hour or so later, Danchise and Boyd watch as Jeff Doxey, owner of Narrowshore Marine, finds the problem: debris in the fuel tank has clogged the pickup tube. Doxey blows the tube clear but warns Danchise.

“I didn’t solve your problem. Whatever it is, it’s back in your tank.” But he offers a workaround. “I’ll make up a longer fuel line for you to carry in case it happens again.”

Danchise thanks him. He and Robert are ready to go fishing again as soon as Hurricane Erin blows by.