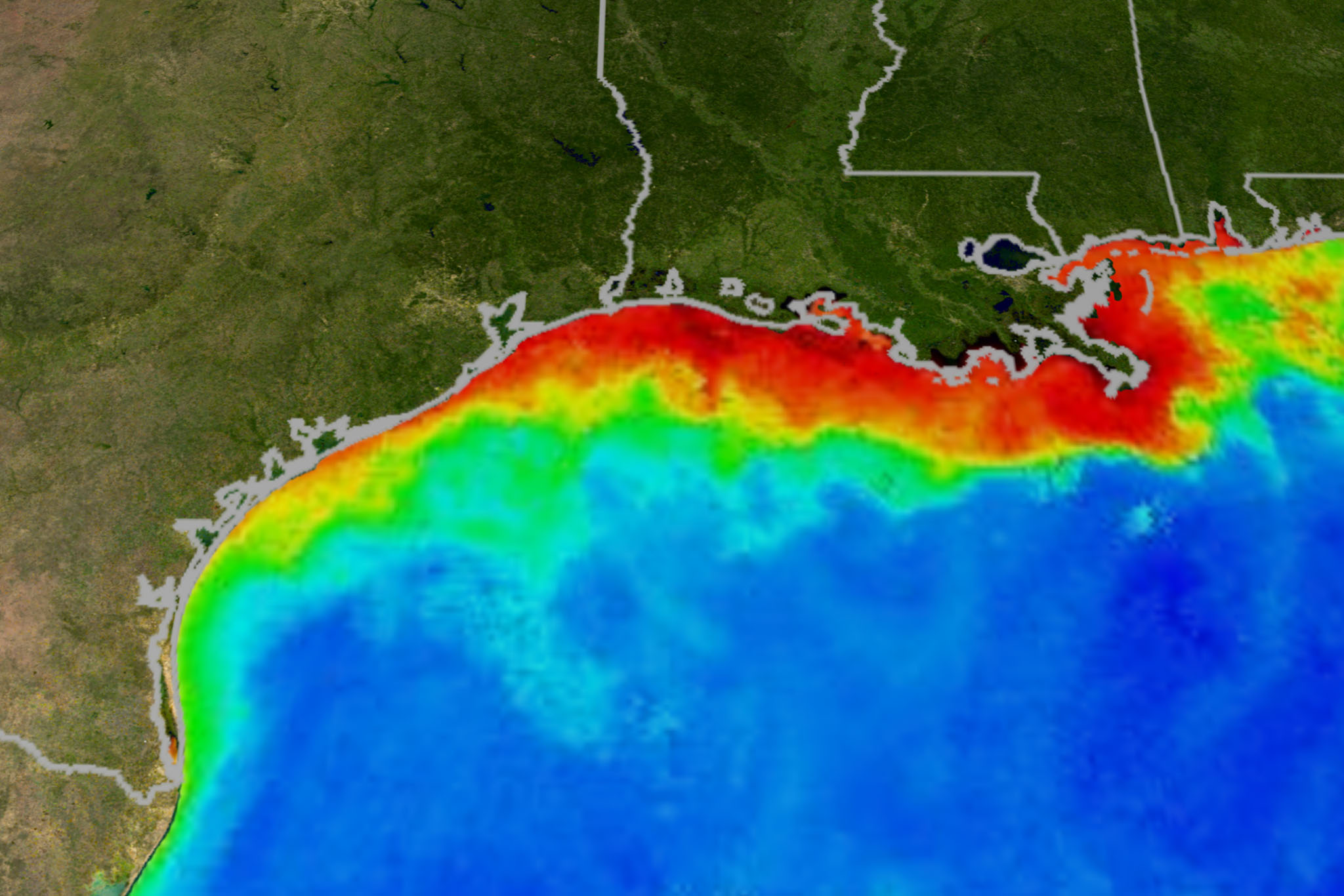

Mississippi basin river flows 30 percent above average will bring an expanded “dead zone’ of hypoxia to the Gulf Coast but fall short of a record-setting 2017 blight, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

NOAA scientists calculate the region of low- to no-oxygen water lethal to fish and marine life will expand to 6,700 square miles at its peak. That’s beyond the average annual measured size of 5,387 square miles, but far short of a record-setting 8,776 square miles of sea – bigger than the land area of New Jersey – that was charted in 2017.

The annual summertime choking out of dissolved oxygen is caused by excessive nutrients – nitrogen and phosphorus compounds that wash out with the rain from farmland and urban centers throughout the vast Mississippi watershed.

The nutrients fertilize aquatic growth as they do crops on land, triggering explosive growth of algae which eventually die and decompose, using up oxygen in the water as they sink. Those conditions drive away or kill marine life.

“Not only does the dead zone hurt marine life, but it also harms commercial and recreational fisheries and the communities they support,” said Nicole LeBoeuf, acting director of NOAA’s National Ocean Service. “The annual dead zone makes large areas unavailable for species that depend on them for their survival and places continued strain on the region’s living resources and coastal economies.”

The annual prediction is based on river-flow and nutrient data compiled by the U.S. Geological Survey, profiling the river flows and nutrient loads that come primarily from the Mississippi and Atchafalaya rivers discharging to the Louisiana coast.

While the spring 2020 high water was nowhere near the record-setting 2019 flood stages, the discharges were still 30 percent above long-term averages recorded since 1980, according to NOAA.

The USGS estimates the May 2020 discharges carried 136,000 metric tons of nitrate and 21,400 metric tons of phosphorus, for nitrate loads about percent above the long-term average, and phosphorus loads around 25 percent above the average.

"The annually recurring Gulf of Mexico hypoxic zone is primarily caused by excess nutrient pollution occurring throughout the Mississippi River watershed," said Don Cline, associate director for the USGS Water Resources Mission Area. “Information on where these sources contribute nutrients across the watershed can help guide management approaches in the Gulf.”

The hypoxic zone forecast assumes typical coastal weather conditions, so the actual dead zone size can be disrupted and shaped by hurricanes and tropical storms mixing ocean waters.

This is the third year NOAA is producing its own forecast, using a suite of NOAA-supported hypoxia forecast models jointly developed by the agency and allied teams at the University of Michigan, Louisiana State University, The Virginia Institute of Marine Science, University and North Carolina and Dalhousie University, along with the USGS.

A NOAA-supported monitoring survey is scheduled for later this summer to confirm the size of the 2020 dead zone. The agency says that will be a key test of accuracy for the integrated models.