Arcing sparks from deteriorated wiring for deck lights and a bilge pump set off an engine room blaze that ultimately sank a Gulf of Mexico shrimp boat despite the crew’s firefighting effort, the National Transportation Safety Board reported in a new safety brief.

The 75-foot steel hulled Lucky Angel was trawling 20 miles off Pascagoula, Miss., at around 10:05 p.m. Dec. 10, 2020 when a smoke alarm alerted the captain.

The captain and two crewmembers emptied fire extinguishers and resorted to buckets of seawater trying to control the fire, before they were forced to abandon the vessel and were rescued by the Coast Guard. The Lucky Angel sank two days later, a total loss of $120,000.

Built in 1968 by Marine Builders of Alabama as the Wahnella Ann, t. he vessel was acquired by Lucky Angel LLC in June 2020. After five days of shrimping and a port call at Bayou La Batre for a doctor’s appointment and groceries, the Lucky Angel departed just before 3 p.m. the day of the accident, and resumed shrimping around 9 p.m.

According to an NTSB narrative, the captain told investigators that during trawling operations he would periodically check the engine room by leaving the wheelhouse and observing the main engine through the aft-facing main deck door to the engine room.

After checking at 9:30 p.m. and 10 p.m., the captain continued to trawl at 2.7 knots until a smoke alarm indicator showed on the wheelhouse panel.

“The captain immediately went to the open engine room door in the after part of the house. He could not recall hearing any unusual sounds coming from the space. From the inside platform, he saw white smoke that ‘smelled pretty much like [something] electrical was shorting.’ He said that he saw sparks coming from a bundle of wires located overhead and slightly to the right of the inside platform.”

The NTSB investigators later determined that the group of wires contained 120-volt AC wires to the deck flood lights and the aft bilge pump.

The captain discharged three dry chemical fire extinguishers into the engine room, he did not close two access doors or two exhaust fan vents to the engine room, according to the NTSB.

“He tried to turn on the deck wash pump, but when he touched the power switch that was located near the platform, he received an electric shock that caused him to fall backwards – investigators later confirmed that the deck wash pump wiring was run separately from the sparking bundle of wires,” the report states.

Back at the wheelhouse, the captain tried to limit the fire’s spread by opening all the electrical breakers that provided electricity to the wheelhouse, which rendered all his bridge equipment, including his VHF radio, inoperable.

Using flashlights, the crew tried tossing sea water from 5-gallon buckets into the engine room for about 20 minutes, until they became exhausted. With the main diesel engine and generator still running, the captain and crew closed all doors and hatches to the house and engine room, except the two exhaust fan vents, and went to the bow of the boat because smoke had now filled the house.

The captain tried to call two other shrimp boats on his cell phone with now answers, then called his wife who eventually contacted the nearby boats. Finally the captain made a 911 call that connected to a local fire department, where a dispatcher routed his call to the Coast Guard District 8 command center at New Orleans at 10:31 p.m. before the cell phone went dead.

About the same time, the boat’s main engine and generator shut down. Coast Guard watchstanders dispatched 45-foot rescue boat was dispatched from the Pascagoula station, while the Lucky Angel crew had launched their life raft that was stowed on the wheelhouse, but the emergency position indicating radio beacon and life jackets inside the wheelhouse were now inaccessible due to the smoke and left on board.

The crew were recovered by the Coast Guard rescue boat at 11:27 p.m. The Lucky Angel continued to burn through the next day and sank Dec. 12 about 3.5 miles south of Horn Island, Miss.

No pre- or post-purchase survey of the Lucky Angel was commissioned, and the captain stated he had made no modifications to the electrical system of the boat, according to the NTSB, which could find no maintenance records for the vessel.

The Lucky Angel successfully completed a mandatory Coast Guard commercial fishing vessel dockside safety exam on May 9, 2017 and was not required to undergo its next exam until May 2022.

Since the main diesel and generator diesels continued to operate after the fire started, investigators concluded the source of ignition was electrical sparking seen by the captain.

“If the wiring was original, dating back to 1968, it may have deteriorated due to decades of being subjected to the atmosphere and chemicals found in a hot engine room environment,” the report notes.

“Chafing from the material used to support the wiring, due to a vessel’s motion at sea or vibration from vessel machinery, could have also caused the wires’ insulation to fail. In either case, a failure in the floodlights and aft bilge pump wiring insulation likely caused arcing, which was the ignition source to the ensuing fire.”

The arcing likely ignited “nearby combustible material (such as fuel or lube oil, grease, rags, or even the insulation to the wiring) to initiate and sustain combustion, which obtained oxygen through open engine room vents,” the report says.

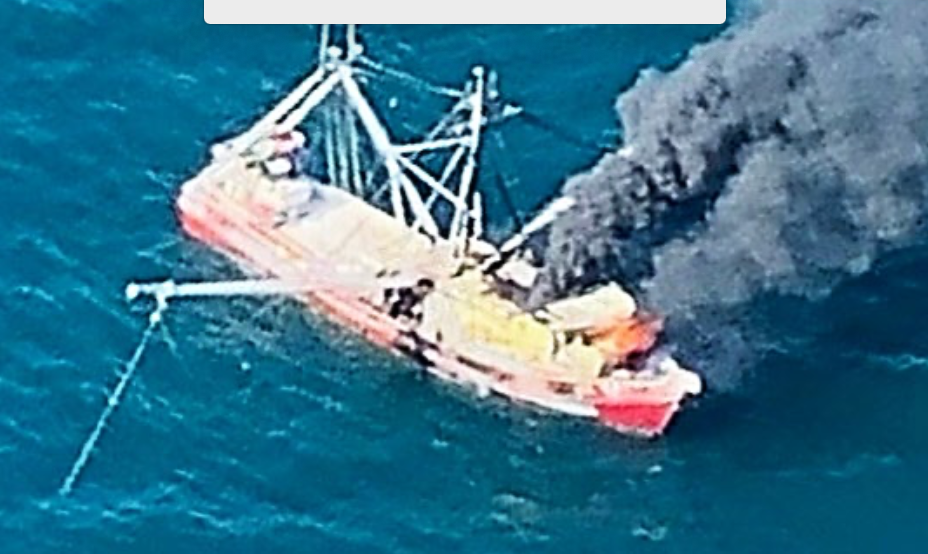

“The fire then likely spread from the engine room to other combustibles in the house of the Lucky Angel as evidenced by the smoke and flames in the picture taken of the fishing vessel on the day after the fire started. Eventually, damage from the engine room fire likely caused a failure in hoses or piping connected to a through-hull fitting for a sea water system that allowed water to enter the hull and sink the vessel.”