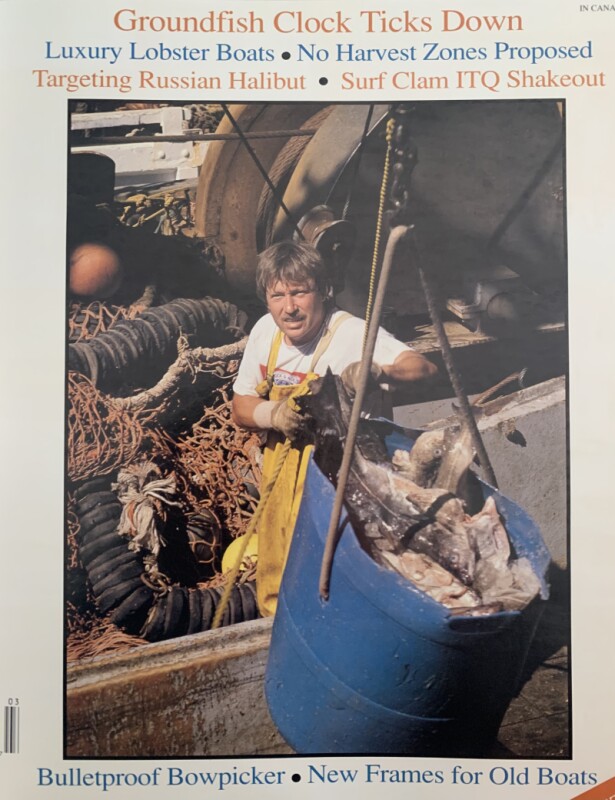

Thirty years ago, NF’s then-editor Jim Fullilove made a prophetic statement on no-take marine reserves.

“The perceived simplicity of the no-harvest zone idea makes it dangerous,” Fullilove wrote on page 6 of the March 1992 edition. “Fencing off reserves is a fishery management tool that could become the darling of politicians and special-interest groups with anti-fishing agendas and little regard for the complexity of fish population dynamics.”

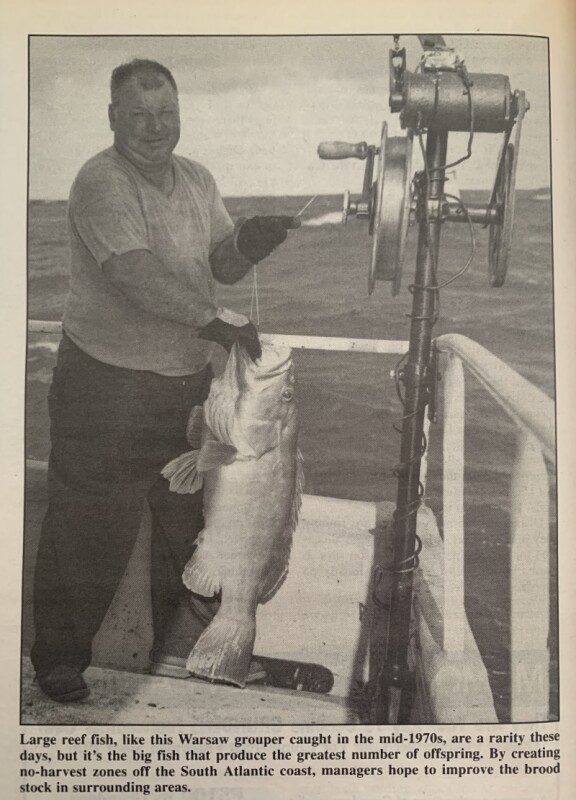

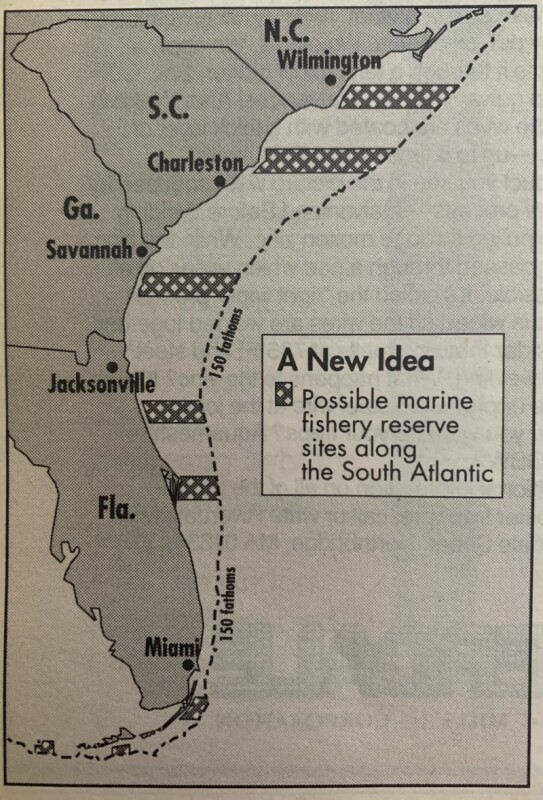

At the time, the South Atlantic Fishery Management Council was considering roping off 20 percent of the coastal waters off of each state in the region to be designated as reserves.

As of Feb. 12, 2009, the council had established eight deep-water marine protected areas off the four states in its jurisdiction — North and South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida.

Despite the fact that the council spent the better part of two decades designing and establishing these areas, there is no conclusive evidence — more than a decade after their implementation — that they are working.

“There was either no change or a decrease in managed reef fish abundance in each MPA relative to adjacent fished areas,” according to a study published in the journal Science Direct in May 2021 (“No effect of marine protected areas on managed reef fish species in the southeastern United States Atlantic Ocean,” Chris Pickens, et al). “Based on these metrics, it does not appear that the SEUS MPAs have yet been effective at protecting managed reef fish species.”

University of Washington Professor of Aquatic and Fishery Sciences Ray Hilborn confirmed in June last year that marine protected areas are essentially regulating a few activities in an area without addressing the full scope of ocean uses and effects from land-based industries and a global pollution problem.

“If you look at what the threats to the oceans are, they’re ocean acidification, climate change, invasive species, various kinds of pollution, land runoff, and none of those are impacted by MPAs,” Hilborn said.

MPAs, he noted, are protecting only from a limited scope of uses.

“Fundamentally, all MPAs are doing is regulating fishing, and maybe oil exploration and mining,” he said. “It’s just the wrong tool. The illusion that you’re protecting the ocean by putting in MPAs, it’s a big lie.”

The best response is a solution tailored for the problem, rather than broad strokes of ocean closures.

“What I would like to see is very explicit targets in what are we trying to achieve in biodiversity, and for each one of those targets, what’s the best tool to achieve it,” Hilborn said. “In almost every case, you’re going to be modifying fishing gear, and how fishing takes place, rather than closing areas to all fishing gears.”

Investment in technology, research and development is considered the pinnacle for every other industry because that is what sets us apart from the animals we hunt. With our ingenuity comes the responsibility of proper stewardship of our finite resources.