For commercial fishermen in the Gulf of Maine, spring typically means fresh haddock.

It’s the time of year when the fish show up thick, boats can finally make steady trips, and crews start to see paychecks that carry them through the lean months. But this year, instead of chasing the fish, Gulf of Maine (GOM) groundfishermen are waiting and watching their quota meters hit zero.

Framework 69, the regulatory vehicle that would increase the GOM haddock quota by 50 percent due to assessments of the stock, is stuck in federal review at NOAA’s level, despite being approved by the New England Fishery Management Council and signed on Dec. 4, 2024.

In the meantime, boats are nearing the limit of haddock they’re legally allowed to land.

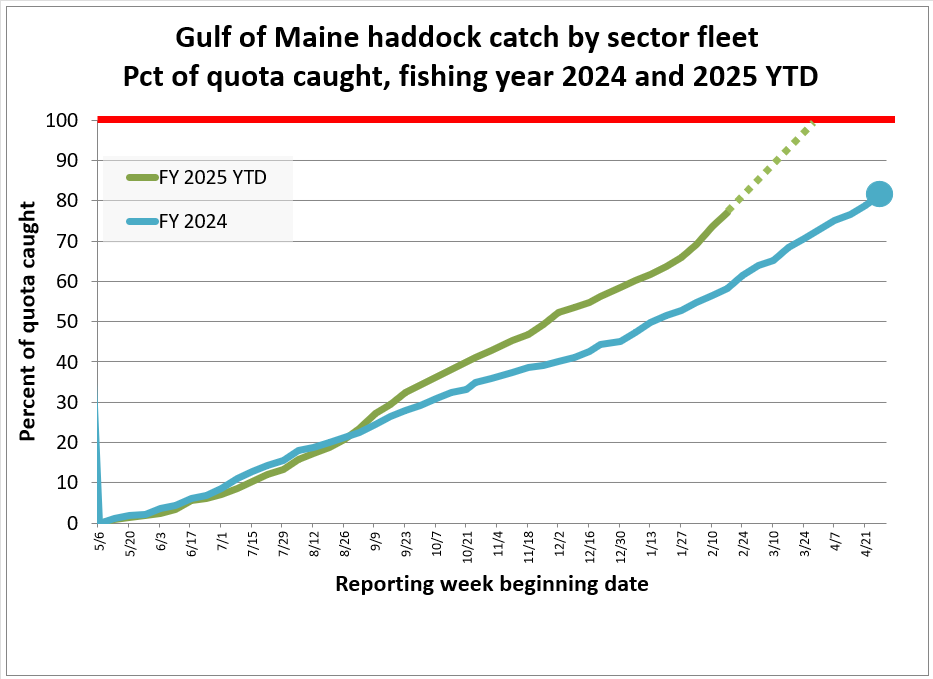

"We were, for instance, four weeks ago, on track at the current quota level to be out of Gulf of Maine haddock quota right around the end of this year,” said Hank Soule, manager of the Sustainable Harvest Sector. New England sectors are self-managed groups of commercial fishing vessels holding limited access permits for Northeast multispecies (groundfish), including haddock.

"Right now, we’re on track to run out of Gulf of Maine haddock quota by late March,” said Soule. For groundfishing, that means a year reset on May 1, which is beyond devastating to fishermen.

A 50 percent increase- Sitting on a desk

Frameworks are the annual regulatory mechanisms that set quotas for the groundfish fleet. Ideally, new quotas are in place on May 1 at the start of each fishing year, but delays aren’t unheard of, and in the most recent years, they have been more common than not across the board for New England fisheries, including groundfish and scallop.

"This year, the framework was delayed again,” Soule explained, pointing to administrative turnover and the government shutdown that stalled regulatory movement. The biggest piece of Framework 69 from the fleet’s perspective is the 50 percent increase in the GOM haddock quota — a bump that fishermen had planned their year around.

But without final publication in the Federal Register, it doesn’t exist on paper.

The proposed rule outlining the Framework was published Dec. 8, 2025, by NOAA Fisheries, yet the approval process has not translated into usable quota on the water. Dave Leveille, manager of Northeast Fishery Sector II and VI, said fishermen have been left waiting for months.

"Framework 69… was signed by the Council in December 2024,” Leveille said. “It has just sat until December 2025. And we’re still sitting here waiting.”

Quota shortage, leasing crisis

The squeeze has been tightening trip by trip, and some fishermen have already tied up.

"The availability of haddock quota to lease had just evaporated,” Soule said. “You can’t get any at this point in time because everybody who’s got some left is rightfully concerned that we don’t know when this framework is going to clear.”

When quota does become available, “the price is extremely high,” Leveille said.

That cost comes straight off the top of a fisherman’s trip. With ex-vessel haddock prices running roughly between $1.20 and $2.25 per pound, there’s little room for inflated lease costs before trips stop penciling out.

All the while, haddock is plentiful in the GOM. “There’s been a couple of times this year where there’s been a lot of haddock around, and fishermen just have to move out of there and not make their tows,” Leveille said. “They can’t catch it because they don’t have enough quota to be able to land the fish.”

Soule said he recently had to tell a boat at sea to leave the GOM area, which spans approximately 36,000 square miles. “I got a call… from one of my boats at sea saying, ‘I think I’m also out of Gulf of Maine haddock quota. Can I get more?’ I said, ‘Absolutely not. You need to get out of the Gulf of Maine. You cannot go negative because we don’t know if we’re going to get any quota.’”

That’s the reality: boats steering away from fish to avoid going over quota, not because the stock isn’t there, but because the paperwork isn’t.

There are two clocks running, Soule said. “The first clock is the end of the fishing year… April 30,” he said. “Your options to be able to use that extra 50 percent of quota are becoming less and less likely as the weeks march by. The second — springtime — is when Gulf of Maine haddock gets caught.”

If the quota increase isn’t implemented before May 1, the opportunity disappears. The fishing year resets, and the unused increase doesn’t roll over for the fishermen even if the GOM haddock stock is there.

For fishermen who structured their operations expecting 50 percent more fish, that uncertainty forces hard choices:- burn through quota now and risk tying up, or slow down and miss the spring run entirely.

The bigger picture of how groundfish is managed

Leveille shared the frustration extends beyond just this delay.

"This is the way we manage now,” he said, pointing to what he described as reliance on limited survey data while fishermen operate under 100 percent observer coverage across the New England groundfish fleet. Managers have access to detailed, trip-by-trip catch data documenting exactly what is being landed and what is being discarded. If that level of real-time accountability exists on every vessel, fishermen are left asking how stock abundance in the GOM can still be misjudged to the point where quota lags behind what boats are seeing on the water.

From the sector perspective, boats are producing real-time data trip after trip, but fishermen still find themselves constrained by a slow-moving regulatory system. And when the quota dries up, so does their income.

According to the NOAA Fisheries, groundfish remains roughly a $40 million ex-vessel fishery annually, supporting hundreds of fishing families, shore crews, processors, and coastal businesses across New England.

When haddock quota evaporates in February/ March instead of stretching through spring, it’s not just a missed opportunity. It’s lost crew shares, lost fuel sales, and lost fresh fish to local markets. Harvesters’ boats are tied to the dock during the most productive season of the year.

National Fisherman contacted the New England Fishery Management Council for comment: "The Council approved Framework 69 in December 2024 and submitted the action to NMFS in March 2025. Almost a full year later, the measures have still not been implemented," said Robin Frede, fishery analyst for the New England Fishery Management Council. "The Council invests substantial time, expertise, and public resources in the development of fishery management actions. This unusually lengthy delay in the regulatory review and approval timeline undermines those efforts and has significant impacts for fisheries and fishing communities, in this case, by preventing the groundfish fishery from accessing the substantial increase in GOM haddock quota that should be available.”

For now, fishermen wait, while some have already been told to tie up, ensuring they don’t go into the negative side of haddock caught, while others fish limited trips. With no better scenario or official paperwork, all will be watching the calendar creep toward April 30.

"Boats have already started to tie up prematurely,” Soule stated.

In a fishery already narrowed by decades of cuts and consolidation, another lost spring is something fishermen can’t afford. Stringent quotas and poor economic conditions for species like haddock and cod have driven many fishermen out of the industry entirely, leaving the fleet at its lowest point in history.