Eric Sloth and his wife threw their belongings into their car and drove to Alaska in 1980. They found their way to Homer (as did this writer a couple of years later). “You know how it was in Homer those days,” says Sloth. “You were a deckhand in summer and a carpenter in winter. I started working with guys here, working on boats, and somebody asks you to patch a hole in a boat, and you start learning, and you end up stretching boats.” Sloth never intended to have his own business, but after 30 years as the owner of Homer Marine, also known as Eric Sloth Boat Builder, he has seen a lot of changes, and facilitated many of them.

“There was a real boom building these seiners in the ’80s and ’90s. Delta, Beck, LeClercq, Hansen were all building small fiberglass seiners. But now, with new boats costing $1.5 million to $2.5 million, fishermen can’t justify that, so there’s a boom on stretching boats. We just finished adding 5 feet to the stern of the Kailee Lynn, and are wrapping up the Thalassa.”

The Thalassa, a 52-foot salmon seiner built at Hansen Marine in Seattle in 1989, is named after the primordial goddess of the sea, Thalassa, who among other things, created all the fish. The vessel arrived at Eric Sloth’s yard in October 2019. Now she is hitting the water as a 58-foot limit seiner with a 50 percent increase in fish hold capacity, an all new RSW system, a new deck layout, a new shaft, and an articulating rudder.

“We added seven feet in the middle,” says Sloth. “I know, the math doesn’t add up.” How does a 52-footer get a 7-foot stretch and end up at 58 feet? “We squared off the bow,” he says.

According to Sloth, the project started with the original drawings sent by Hansen Marine. “They were paper drawings,” says Sloth. “We had to upload them into our program.” Sloth uses the Rhino CAD vessel design program with Orca, which enables him to create 3-D imagery of the entire project, and also see how a vessel will lay under certain conditions. The Thalassa was built with a 65,000-pound fish hold capacity, which Sloth increased to 100,000 pounds.

“We designed three new fish holds,” he says. “He’s got a small 20,000-pound hold forward, for when things are slow and he doesn’t want to tank up the whole boat. Then there’s a 50,000-pound hold that kind of wraps around that, and a 25,000-pound hold behind that.”

Besides designing the tanks, Sloth had to design the 18-ton refrigerated seawater system that will enable the Thalassa to land top quality product.

“We got the chiller from IMS and the condenser from Cold Seas. Mark Volinski at Cold Seas customized that for us; my son worked for them.” According to Sloth, he has piped the system mostly with 4-inch, schedule-80 PVC. The main circulation pumps are electric and run off the genset, the hydraulics run off the main, a 500-hp 6140 Lugger.

With the addition of 7 feet, the Thalassa needed a new shaft. From the Twin Disc MG 5111 with 2.5:1 reduction to the 36 x 28 propeller, Sloth’s team installed a single 3-inch-diameter by 28-foot Aquamet-22 shaft — no tail shaft. “It’s the biggest one they make,” says Sloth. “They shipped it from Boston, by truck and then barge.”

Lining up a shaft that length took some time. Sloth reports they shot a laser line up from the shaft log to the transmission coupling, and used that to line up one cutless bearing and one grease bearing midway between the Twin Disc and the PSS dripless stuffing box. They then soaped up the shaft and slid it into place. “We have a Morse taper on it,” says Sloth. “I stay away from oils and anti-seize when fitting the propeller. I want the prop to seize onto the shaft.”

Sloth notes that they also use the laser on the transmission coupling to line up the two parts of the hull once it is cut in half. The original hull was built with a 1-inch solid-glass bottom and 3/4-inch sides. “We have to keep the sides and shaft angle in line,” says Sloth. “Every stretched boat has some ugly geometry, but this hull was almost perfect. We cut her at her widest point, so that helped,” says Sloth. “We kept the sheer and sides, but sacrificed a little on the bottom.”

While adding a half-inch of glass over the 7-foot extension, tapered along 20 feet of the hull, Sloth built up the inside to as much as 2 inches, again, tapered into the original. “It’s like we built a new hull inside the old one,” he says. The Thalassa has heavily gusseted bulwarks and double cleats for tying alongside tenders in rough weather.

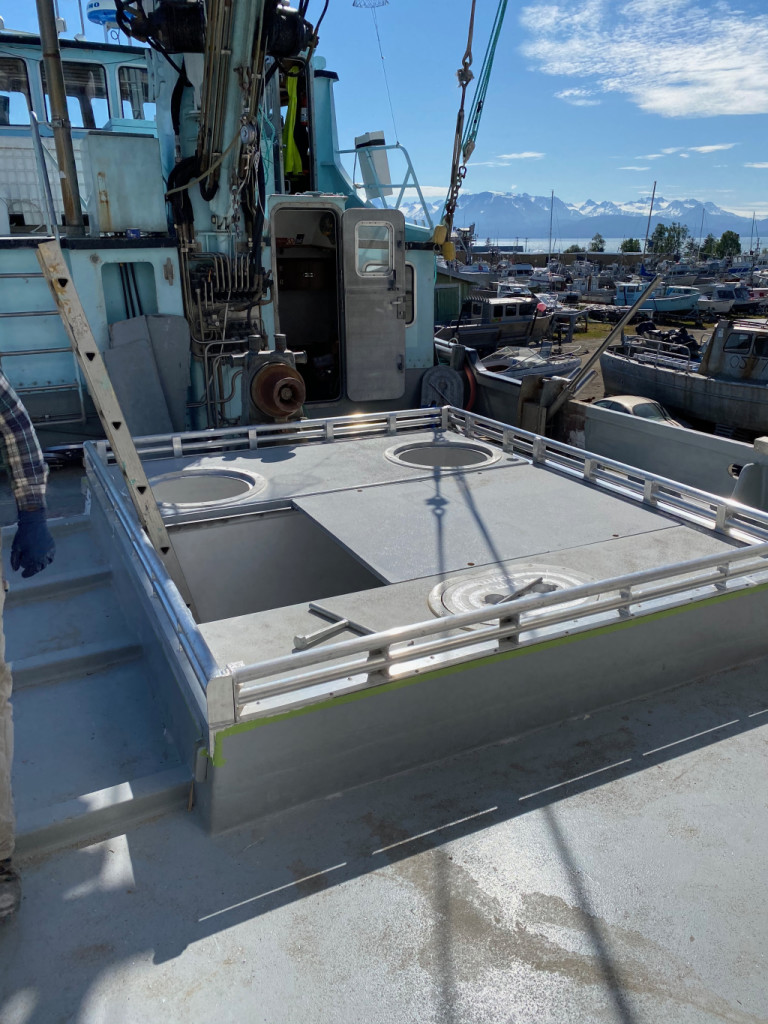

The new deck is 1.5 inches thick and includes a false deck that sheds water and protects some of the piping and wiring that runs aft. “We put a big chaseway and used the same schedule 80 PVC, 4-inch and 3-inch for air, drinking water fuel lines and the autopilot for the articulating rudder, and some new wiring.”

Among the new features on the Thalassa, Sloth installed an articulating rudder. “It’s the same design as the Lowell, (see NF Oct. ’19) but we got it from a guy in Palmer.”

Sloth points out that the false deck helps provide a safer work platform when the crew is handling large bags of fish dumped on deck. “The two goals of this project were to increase capacity and put fish onboard fast. If they can shave 15 minutes off loading time every set, that adds up. We designed what we call a fish corral to help get fish down fast. So they can get one load down while they get ready to roll another 5,000-pound load aboard.”

The vessel increased hold capacity, but left fuel capacity the same. “We did increase her fuel capacity five years ago,” says Sloth. She’s got two 1,000-gallon tanks in the stern.

Because of the hull design, the Thalassa makes only about 8 or 10 knots, according to Sloth. “Usually with an extension we gain a knot or two. There’s more planing surface, and the boat gets up a little more.”

The Thalassa will fish around Kodiak and Shelikof Strait, chasing reds, humpies and some dog salmon. Unlike many East Coast boats, the Thalassa tows its seine skiff rather than hauling it up a stern ramp. The seine skiff holds one end of the seine in place while the boat deploys the net in a circle around a school of salmon.

“They have a Bay Weld skiff, made here in Homer,” says Sloth. “It’s a 20-foot jet skiff with a John Deere 6090. They just snug it up to the hawsehole aft.”

According to Sloth, the Thalassa is his sixth vessel extension. “The first one was 4 feet,” he says. “I brought an engineer in for that one. I don’t have any education or credentials for this work, just 30 years of experience. I’m very serious about the engineering, I read everything, go to the shows, and talk to people.”

Sloth credits a lot of his success to his neighbors working in the fishing industry. “I didn’t know anything about rewiring a boat, so I called David Mogar at Specialty Electric, and he was too busy. But he told me what I needed to do and stopped in to see how things were going.” Sloth notes that after a few boats, he pretty much knew what to do.

“I’m lucky to be part of a great community of skilled people,” he says.