With most of the world’s commodity fisheries under some form of quota management, fishermen who want to increase profitability are looking at delivering the highest quality products to the markets — to do that, they rely on refrigeration.

In some cases, such as Louisiana shrimper Lance Nacio’s AnnaMarie shrimp operation, refrigeration is as simple as putting a freezer unit on the deck of his boat. But in many fisheries, adding and improving refrigeration and freezers is an integral part of the vessel design process.

“We did that with Lance,” says Kurt Ness, of Integrated Marine Systems. “We’ve done many other projects down there, working primarily with a company called Williams Fabrication in Bayou La Batre [Ala.]. We did some lobster and crab live systems, and we did a prechiller and other systems for an East Coast scallop boat built by Fleet Fisheries in New Bedford [Mass.].”

While many East Coast fisheries still rely on ice from shoreside suppliers to keep fish fresh, fisheries in the distant waters of Alaska are another matter, and according to Ness, that’s where IMS puts most of its focus — primarily in the Bristol Bay gillnetter fleet and other boats, like seiners, trawlers and tenders that use refrigerated seawater.

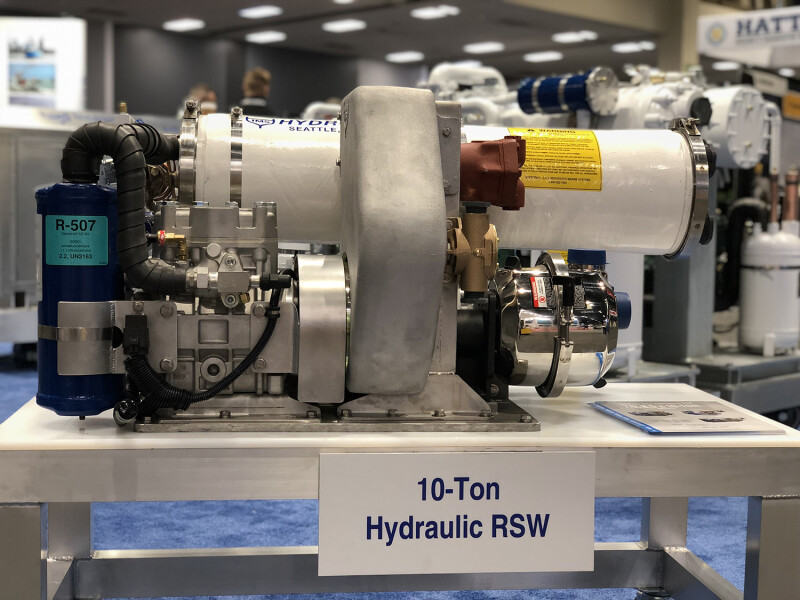

“We offer a wide range of products from 3-ton through 60-ton self-contained RSW systems,” says Ness. IMS works with a number of builders of Bristol Bay boats, such as Basargin Boats in Alaska, Mavrik Marine in Washington, and builders of larger craft, like Fred Wahl in Reedsport, Ore. He notes that while there is often a lot of back and forth with builders and owners to determine the best system for the boat, with other builders, it’s plug and play. “We supply all the RSW for the beautiful seiners Fred Wahl builds,” says Ness. “We just send them the equipment, and they do the install.”

IMS also did a 10-ton titanium keel-cooled RSW system for the Haldrada, a Bristol Bay boat built by North River in Roseburg, Ore.

“The keel-cooled design is going to work great for jet boats that go into the shallows, due to the closed-loop condenser circuit, as opposed to raw water being pumped in — think of the debris that can be sucked up into the system via the condenser pump,” says Ness. He points out that with the keel-cooled system, the condenser loop includes a “holding tank” of water that is then circulated through aluminum pipes — keel coolers on the bottom of the vessel.

For big boats, Ness suggests several IMS 60-ton systems. “If a boat packs a million pounds of product, for example, you can go with one massive system and risk something going wrong with it and then losing your tendering or fishing season, or go with several smaller systems and have the assurances of redundancy,” he says.

IMS setups are powered with either electric, hydraulic or diesel drive.

“The diesels are powered with a 3-cylinder Isuzu engine mounted onto the unit,” says Ness. He notes that IMS usually sells its products on a self-contained skid for easy installation and reduced chance of leaks.

“We also provide standalone components for various reasons,” says Ness. “Most commonly due to space constraints on the vessel.”

Pacific West Refrigeration, in Saskatchewan, Canada, is another company focused on the West Coast — of Canada — but also supplying East Coast boats. “We sell a lot to the snow crab boats in eastern Canada,” says company owner, David Nowell. “And we did some freezer cabinets for slime eels, for some boats in Maine. Those were custom built.”

According to Nowell, some crab boats have gone to single-phase generators, “so we started building single-phase packages. We just finished one, a 36-ton that has six Copeland scroll compressors on it in parallel. The nice thing about them is that because they’re only 6-hp they start up really smooth, not like if you were starting a 36-hp. We built that in order to fit with the single-phase generators where you can run computers and stuff, and it’s a cleaner power.”

According to Nowell, the company has concentrated on building transom coolers for Bristol Bay gillnetters. “We build transom coolers and keel coolers. We kind of stopped building the keel coolers. There’s a few out there, copper nickel on fiberglass boats and aluminum on aluminum boats. Pretty much most of the new jet boats go with Signature Pac West transom cooler.”

Nowell built his first transom coolers with Tom Aliotti at NTG, in Everett, Wash. “There were a lot of guys that said they wouldn’t work — and they don’t work so good when we test them in our shop — but up in Bristol Bay, they work like crazy.” Nowell and Aliotti got together to figure out a new system because Aliotti didn’t want the drag of the cooling pipes. “Before long, more guys jumped on, and they’re building more and more every year.”

While the transom cooler chills the refrigeration systems, Nowell notes that the boats use skin coolers to cool the engines. “Just two layers of aluminum. But for the refrigerant, you need too much cooling. You’d run too high a head with a skin cooler.”

Nowell got his start in the refrigeration business making ice for skating rinks. He went from there to freeze walleye from the freshwater fishery in Lake Athabasca located in the far north of Saskatchewan. “I still buy the walleye from up there,” he says. “And that is a good eating fish.”

While companies like IMS and Pacific West can build units on skids for easy installation, refrigeration systems on larger freezer trawlers and longliners require much more cooperation between manufacturers and vessel designers. Osman Colak is the CEO of Teknotherm, the U.S. branch of Teknotherm Norway, which is in turn owned by the Dutch company Heinen & Hopman.

“We are partnering with a lot of vessel designers,” says Colak. “We work with Skipsteknisk, Kongsberg, Salt, and many other designers in Norway, as well as local consultants in the U.S.” Colak points out that while Teknotherm also does high-capacity RSW systems and ice machines, they are best known for plate freezing, cargo freezing, and IQF systems.

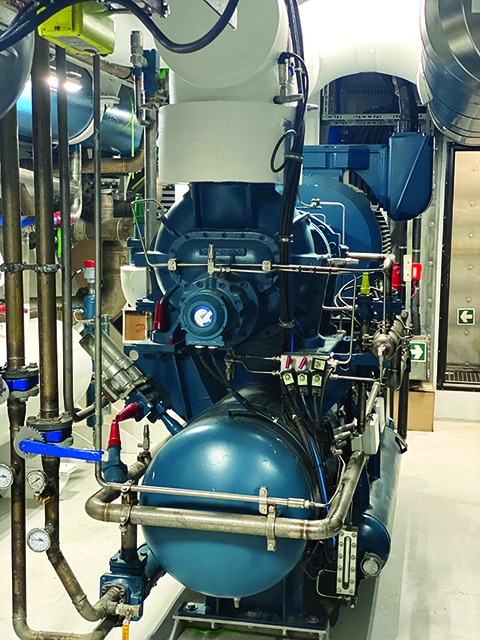

“We are manufacturing many components in-house that are crucial for the system — compressor skids, chillers, condensers, and some other supporting equipment like pressure vessels and level indicators. When it comes to electrical components, we are building them in our shop in Seattle. We are doing all the software design and building control cabinets ourselves, and this is our main strength in the market.”

Teknotherm has been a key player in producing refrigeration and RSW systems on catcher-processors such as for North Star, America’s Finest, Nancy Elizabeth, and many others. “In the design process with Skipsteknisk, for example, we offer technical support, and are on the makers list,” says Colak. “That is the shortlist of suppliers that the designer recommends to the owner or the yard.”

According to Colak, freezing and cold storage areas usually consume upward of 30 percent of a freezer-trawler’s hull space. Teknotherm systems for large vessels are electric powered. “If a boat is freezing 200 or 300 tons a day, they may have a generator producing around 1,000 kW,” says Colak.

Among the newer innovations for large-scale refrigeration systems is the refrigerant itself. Colak points out that many systems are switching to natural refrigerants. “Majority of the vessels in the U.S. fleet are using R22, which was phased out in 2020. R22 is still available, but in the next couple of years, all the vessels will consider switching to ammonia and CO2,” he says.

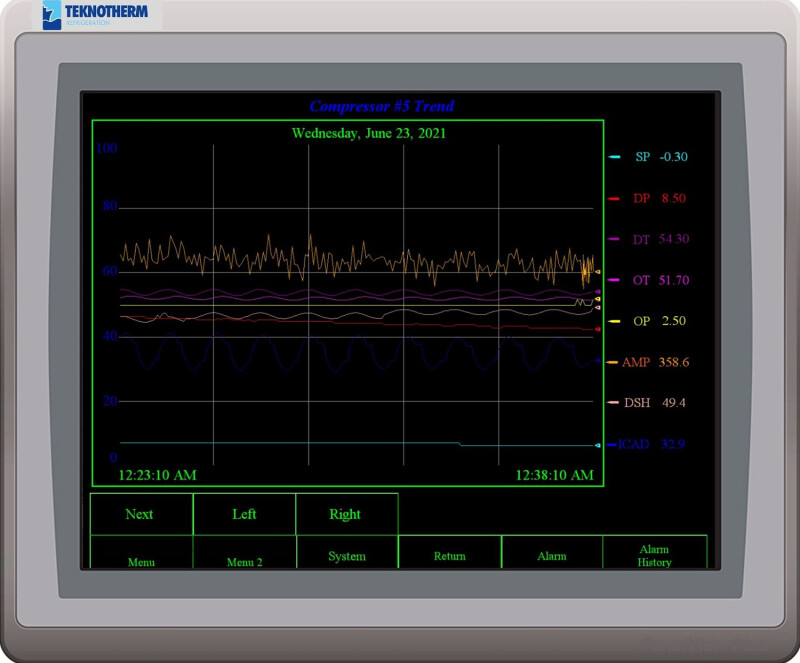

What most excites Colak is automation and remote system control via satellite. “We’ve started putting remote control on all the systems that we provide,” he says. “We can connect to the main communication system on the vessel and see how the system is performing and what kind of issues they are facing, and we can make improvements remotely without a service technician getting on the boat. Furthermore, we are able to deliver fully automated refrigeration systems that are capable of running without operator interference.”

According to Colak, customers with boats in the Bering Sea are able to monitor data like cargo hold and RSW temperatures, power consumption, NH3 Concentration, and amount of refrigerant in the system, and tracking for EPA, from their offices in Seattle. “Users prefer this,” he says. “They can see the performance history and increased efficiency.”

From big boats to small boats, innovation is improving efficiency in refrigeration and increasing the quality of the seafood these boats bring to market.