Up until the 1960s, wooden boats dominated the North Pacific fishing fleet. Over the last half century, new technology and new boats have expanded fisheries and given birth to multimillion-dollar businesses.

In 2016, the McDowell Group released a report, “Modernization of the North Pacific Fishing Fleet,” which focuses on the more than 400 vessels measuring 58 feet and up in the fleet of 5,000 fishing boats and tenders. Noting that the average boat in the fleet is 40 years old, the report predicts how the replacement of an aging fleet will play out. According to naval architects in the vanguard of vessel design, the evolution of the fleet will be shaped by fisheries management, the Coast Guard Authorization acts of 2010 and 2015, technological advances, and the fluctuations of fish stocks, quotas and prices.

This story appears in the December issue of National Fisherman. Subscribe today for digital access and print.

One of the biggest issues naval architects grapple with in designing boats to meet the needs of fishermen who want to build new or do major conversions, are the legislative changes in the Coast Guard Authorizations Acts of 2010 and 2015.

“The problem is that the lion’s share of the legislation is not written into the regulations,” say Hal Hockema, of Hockema Whalen and Myers Associates, a Seattle-based vessel design firm. “Here we are eight years out and we do not have complete regulations for new vessels.” Currently vessels 50 feet or greater, built after Feb. 8, 2016, must be classed according to American Bureau of Shipping standards or their equivalent, and boats 79 feet and larger must also be load-lined. “The problem for boats in the 50- to 79-foot-range is that the equivalencies have not been clarified,” says Hockema.

In addition, Congress added a new mandate for the Coast Guard to develop, in cooperation with the commercial fishing industry, an Alternate Safety Compliance Program for all commercial fishing vessels 50 feet and up that were built before July 1, 2013, particularly those that will be more than 25 years old by 2020. The program also applies to commercial fishing vessels built on or before July 1, 2013, that undergo a major conversions completed after July 1, 2013. The legislation originally required that the Coast Guard put the program requirements into regulatory form by Jan. 1, 2017, with implementation beginning in 2020, but those dates have changed.

“The problem for boats under 79 feet is that they are not in the mainstream of ABS standards,” says Hockema. “You can substitute with a plan from a licensed professional engineer that is equivalent to classification standards. For example, we may choose a Coast Guard approved electrical system from a similar size passenger vessel.” But Hockema points out that this could lead to problems when the regulations are finalized. A boat built using what may seem like a responsible design may not meet the Coast Guard’s still undeveloped criteria. “The owners could find themselves out of compliance and might have to do substantial work to meet the regulations.”

Hockema, who sits on the Commercial Fishing Safety Advisory Committee, which works with Coast Guard to develop workable regulations, expresses some frustration with the process. “I know the Coast Guard did substantial work on this. In early 2017 it was in final draft form, but never issued. It’s rather embarrassing, because in terms of fishing vessel safety I think we’re falling behind Europe and Japan.”

Another program, the Alternate Compliance Safety Agreement, provides a means of complying with the regulations for larger boats that cannot be classed.

Jensen Maritime wants to convert oil rig supply boats from the Gulf of Mexico into new freezer trawlers for Alaska. Jensen Maritime image.

According to Jonathan Parrott, vice president of new design development at Jensen Maritime, Jensen focuses on larger vessels and has avoided the headaches associated with the Coast Guard Authorization Acts. “Most of our vessels are built according to ABS standards,” says Parrott. He notes that new stability criteria has provided Jensen a steady stream of stability work.

“That’s the bread and butter for most naval architects,” he says. Since 2006, catcher processors that cannot be loadlined or classed, because of their age, can opt into the alternative agreement, which requires a stability test every five years. “ACSA is specific to the Pacific Northwest,” says Parrott. “It was developed after a series of casualties in Alaska and has made a tremendous contribution to safety. We bring the boat in and incline it,” he says. “It’s an exercise where we go aboard with a series of weights and shift those around to determine the boat’s center of gravity and how it changes.”

Engineers then take the numbers back to their computers and combine them with the boat’s specs to develop a stability booklet with recommendations for safe deckloads under various conditions. “It’s important to remember that these criteria establish an estimate of probability,” says Parrott. “They can be exceeded under certain conditions. In other conditions a boat may be within the criteria and still capsize.”

While older catcher processor boats working primarily in Alaska must have stability tests every five years, boats like the crabber Destination, lost in the Bering Sea in 2017, do not fall under these requirements. “There are boats out there with no stability work since 1982,” says Parrott. “I’m afraid they’re putting themselves in harm’s way.”

In the case of the lost crabber, Destination, which was last inclined in 1992, the actual weight of the crab pots on deck was several tons greater than their estimated weight, skewing its stability assessment. “If you add a few tons of weight, you have less freeboard and less stability,” says Hal Hockema.

While intended to increase safety, all the new rules are driving up costs, especially for new builds that require surveys during construction. In addition, some of the rules make little sense for fishing vessels.

“The marine safety rule-making process is broken,” says Pat Eberhardt, owner of Anchorage-based Coastwise Corp., which recently worked with Kodiak fisherman Kent Helligso on the F/V Evie Grace.

Eberhardt’s company produced a 300-page stability booklet for Helligso’s boat. “We did more than 16 stability iterations of 500 conditions each — 8,000 in total.” Nonetheless, the Coast Guard rules call for a loading mark. “Fishing boats are the only boats that gain weight at sea,” says Eberhardt. Making the use of a loading mark as a criteria for stability is “an ill-advised idea that could be dangerous,” Eberhardt says. Instead he advises fishing boat owners to continue to rely on their stability booklets and not the loading mark. “We’ve brought this issue to the attention to the Coast Guard, but we haven’t heard anything back.”

In spite of the difficulties designers have in adapting to the rules, the McDowell Group study of fleet modernization paints an overall optimistic, if somewhat lopsided, picture of the future, with most new construction going into larger boats. But because costs are higher in the United States, designers have to chase efficiency everywhere they can.

Where the old wooden schooners that made up the bulk of the fleet before the 1960s and ’70s, were built from half models carved by knowing eyes, naval architects now use computers. “We use a surface modeling program called Orca 3-D, which runs in Rhino. It allows us to design the hull with extreme accuracy Eberhardt says”. As part of the process, he Eberhardt prints a small-scale version of the design in a 3-D printer. “I want to see it and put my hands on it,” he says. “I like to feel it.”

Holding the model, Eberhardt is keenly aware of the economic realities fishermen face, and he works closely with them. “If the fisherman is in the design loop, the boat’s going to fish,” he says. “But a fishing vessel costs a lot of money, and nowadays they have to be highly designed to bring the most product to market as efficiently as possible.”

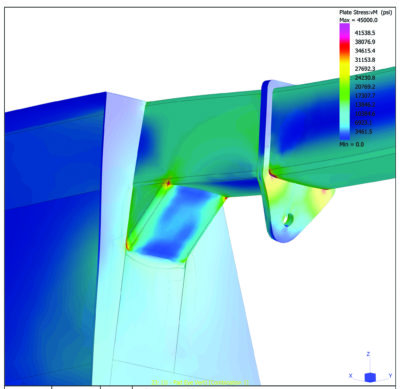

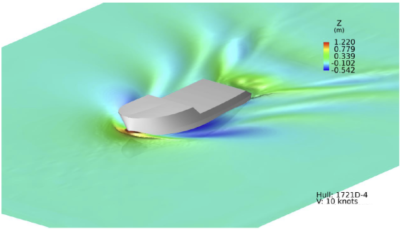

- Computer programs help naval architects maximize efficiency. Finite element analysis indicates stress point on a gantry, enabling a lighter build. Computational fluid dynamics helps to refine hull shapes to optimize speed and fuel efficiency.

While using Orca 3-D to create the hull design, Coastwise’s engineers use computational fluid dynamics to maximize efficiencies. This modeling enables them to refine the hull to reduce resistance and achieve the optimum balance of speed and fuel consumption.

“This isn’t new, but now it’s affordable,” says Eberhardt. “Ten thousand for an annual license.”

Coastwise also uses the program Finite Element Analysis for structural optimization. “That allows us make the lifting gear like gantries and masts lighter, which lowers the center gravity,” says Eberhardt. A lower center of gravity, he points out, increases the stability of the boat, enabling the owner to put more fish aboard safely.

When Eberhardt and his client are satisfied with their design, the boat goes to the lofter. “Once it leaves here, we don’t allow any changes to the hull shape,” says Eberhardt. “They take our design information and turn them into instructions for the steel fabricators and the yards. What the yard gets is almost a kit,” says Eberhardt, albeit an extremely complex one.

In spite of the challenges, new boats continue to be launched, and while the McDowell Group report sees more replacement vessels going to the catcher-processor fleet, it also acknowledges significant activity across all sectors with the exception of crabbers. Most designers remain generally optimistic. Jonathan Parrott at Jensen Maritime is excited about converting platform supply boats from the Gulf of Mexico into new catcher processors.

“There are 300 to 500 vessels down there, of which about 12 to 24 are suitable for conversion,” he says. Parrott estimates that conversion would cost somewhere between $30 million and $60 million, in addition to the cost of the vessel. “These are potentially good platforms,” he says. “At a lower cost than building new.”

Hockema and Eberhardt, both of whom once worked at Jensen, see a regulatory bottleneck throttling the ability of fishermen to build smaller and medium-sized boats affordably. While Hockema is OK with regulations that establish a baseline for equivalent standards, he is frustrated by the lack of equivalency for all systems. “I don’t understand why we can’t just build good boats,” he says, referring to the stalled rule making process.

Eberhardt echoes his sentiment.“We have the ability to bring efficient designs to market,” he says. “We just need to improve the fisheries economics and the regulatory environment so that fishermen can afford to build them.”