Watching hake and rockfish swimming hard as they slip down the narrowing throat of a midwater trawl, it’s clear the net catches everything. But not everything belongs in the net. Alaska salmon, certain Pacific rockfish, and Atlantic cod are among the species midwater trawler captains work to avoid.

Under the banner of conservation engineering, fishermen, regulators, marine electronics manufacturers, and net makers are working on a number of innovations — new bycatch excluder designs, LED lights, and cameras — that are helping midwater trawlers reduce bycatch.

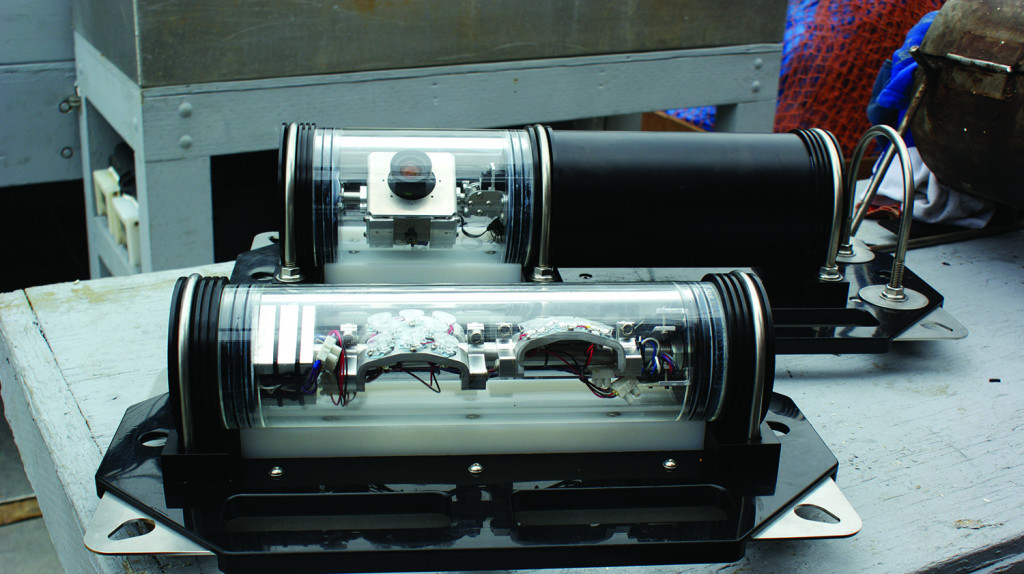

“Bycatch is the number one reason fishermen buy the system,” says Jason Whittle, vice president at Ocean Systems. Ocean Systems’ SeaTrex, according to Whittle, is a simple but robust color camera that runs on a third wire and uses 1,500-lumen white lights and a wide-angle lens to help fishermen see what’s going into their nets.

“With rockfish, you have to see the colors to know which ones you’re getting, and that requires white light,” Whittle says, noting that his company’s focus is on imagery. (Whittle offers up a YouTube video of fish going into a net to lure curious fishermen: tinyurl.com/seatrex.)

Whittle points out that all camera controls are preset when the device goes overboard in the net. That means all the capacity of the third wire is used for transmission from the camera.

“Our cameras are very simple,” he says. “The less information you have going up and down that wire, the better the quality of the image.”

Keeping it simple makes the cameras affordable and easier to service, Whittle points out. “Our system is under $50,000,” he says. “And in the two years we’ve been selling them, we haven’t really had any service issues.”

Other marine electronics companies — including Simrad, Wesmar, and the newcomer SmartCatch — are using cameras to monitor bycatch as well as performance of escapement designs that use fish behavior to help salmon and other species get out of the net before it is hauled.

Rob Terry, co-founder and CTO at SmartCatch, also touts the price points of the $40,000 SmartCatch system. In response to the needs to the fishermen he works with, SmartCatch has a moveable camera with adjustable lights.

“We’re designing the next version so you don’t have to take it off when the net goes onto the reel,” says Terry. The F/V Constellation in Alaska, and the Excalibur out of Newport, Ore., are among the vessels using the SmartCatch system, and Terry reports good results.

“Mike Retherford, who runs the Excalibur, makes more money on hake than rockfish,” says Terry. “He can clearly see on camera when rockfish are going into the net and move right away to where he can find hake.”

Besides being used to avoid bycatch, most of these camera systems are also being used to monitor bycatch excluders.

“Simrad started making its FX80 trawl cam in 2012,” says Mike Hillers, general manager at Simrad Fisheries. “Fishermen were putting together salmon excluder devices per regulation, and not getting good results. Then the government put a hard cap on salmon bycatch and said just do it. Every fisherman was trying something, but they could not see what was getting out.” According to Hillers, fishermen checked the effectiveness of their salmon excluder efforts with a recapture bag to see how many fish were getting out.

“The thing is, that killed the fish, and they had no way to see what was actually happening. Some companies were using recording cameras, and it was somebody’s job to watch all that recorded footage. We put a camera system on a third wire, and fishermen could watch the flaps on the salmon excluders to see if they were open, or if they closed when turning, and if they were going too fast, so they could make adjustments.”

According to Hillers, the FX80 runs for around $80,000. He notes that it has proven reliable and had only a few upgrades. “Not a lot,” he says. “We’ve resized it and added color cameras.”

Hillers notes that he works with NOAA, holding workshops that involve fishermen and netmakers to help figure out better ways to reduce bycatch.

“It’s mostly theoretical, we talk about what we’re doing and what we think might work. We’re also working on a number of projects on the East Coast, and we’d like to do more. Not too many boats there have a third wire, so we’re looking at using wireless echo-sounders to monitor what’s going into the net,” says Hillers. Cod is the choke species East Coast fishermen try to avoid. “We want to fly the net just off bottom,” he adds. “So we catch haddock and not cod.”

Seattle-based marine electronics manufacturer Marport is not making cameras yet.

“We’re looking at it,” says Patrick Belen. “When we get ready to roll something out, it has to be the best.” Marport currently works with fishermen using the company’s net sensors to reduce bycatch. “We have a pitch and roll feature we add to the catch sensor, and it can detect when the excluders are working,” says Belen, noting that he works directly with fishermen via video link to learn how to interpret the information they are getting from their sensors. “They correlate that with other parameters to know when the panels are open.”

NOAA’s Noelle Yochum is a regular contributor to these innovation efforts.

“I started working on reducing bycatch in the East Coast scallop fishery,” says Yochum. “I fell in love with fishing gear and working with fishermen on how to make this work. Fishermen are the real innovators.”

Yochum moved to the West Coast and started looking at the salmon problem for Alaska’s midwater trawlers. Working with a number of net designers, including Swan Nets, LFS, and Net Systems, Yochum is looking at how to convince more salmon to leave the net.

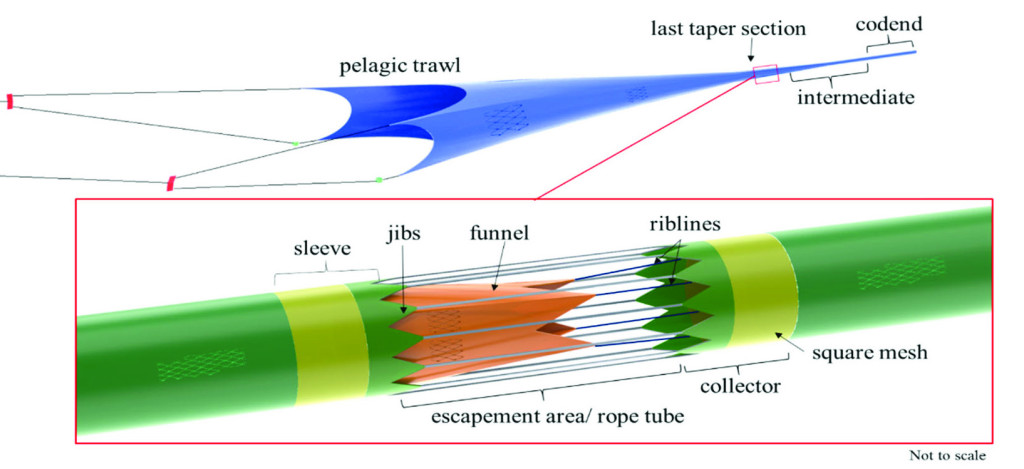

“We were seeing high variability in escapement,” says Yochum, whose paper on the subject details the unpredictability of salmon escapement, even with the rope tube and funnel salmon excluder she helped design. “The question is: What are the behavioral mechanisms driving escapement?” says Yochum.

“Michael Stone and I started thinking about what would happen if there is no barrier to escapement. There were a lot of napkin drawings,” Yochum adds. She and Stone came up with a salmon excluder that amounts to a section of net near the cod end that consists of nothing but a tube of ropes. A funnel that extends into the rope tube, shoots the pollock toward the cod end while letting the stronger swimming salmon escape.

“Seamus Melly at Swan Nets put it together for us, and we took it to the flume tank in St. John’s [Newfoundland] in 2019.” The trials in 2020 led to higher but variable escapement. “Even with almost no barrier, we still had 42 percent retention,” says Yochum. “The fish were not perceiving a threat, they were not motivated to escape.”

“The fish don’t know they’re in a net,” says Koji Tamura, a designer at Net Systems in Seattle. “We’d like to put a sign: Pollock this way; others that way.” To that end, Yochum has worked with folks at Net Systems to design kites that increase excluder openings, and noting that fish behavior appears to be affected by what’s happening in their visual field, she is also working on using LED lights to help guide fish out of the net.

“We tried putting them around the edge of the excluder,” she says. Besides salmon, Yochum wants to use LEDs to reduce halibut bycatch. “Next summer we’re going to try use blue LEDs to keep halibut from even going into the net,” she says.

Shea Kirkpatrick, a net designer at LFS in Seattle, has built a salmon excluder that uses fluid dynamics to encourage escapement.

“We call it the Baskin-Robbins,” says Kirkpatrick. “It has a top scoop held open by floats and a bottom scoop that’s weighted. The top and bottom scoops touch on the inside, creating water flow down the inside side panels. This is to allow the target species to pass through to the cod end while the openings created by the scoops allows salmon to escape.”

Like Yochum, Kirkpatrick also has some ideas for reducing halibut bycatch. His halibut excluders feature panels in the throat of the net that shunt halibut toward grids made of stiff vinyl cable, giving the flat fish a chance to escape.

While some of the techniques and devices for bycatch reduction have been in play for a number of years, net designers and electronics companies continue to push the envelope and enable fishermen to fish clean.