Alaska fisherman and Fisherpoet Pat Dixon’s memoir is the story of a young greenhorn from Indiana, who ventures into the fishing life and makes it his life

Waiting to Deliver: From greenhorn to skipper, an Alaska commercial fishing memoir

$15.99

Author’s note: The first part of this chapter describes being off by myself at the end of a good fishing day, and getting into them again. I call my friend Don Pugh over to get in line with me, and he gets in on the action too, right at the end of the period. We are running home as it starts to get dark, loaded and slow, we are the last boats to leave the grounds.

I’m asleep in the bunk when the drone of the engine goes quiet.

“Hey, Pat,” Danny calls, but I’m already wide-awake and getting up. It’s almost 9:00 pm under gray skies, and the light is dim outside.

“What happened?” I ask as I look out the windows. I think Danny shut her down for some reason.

“I don’t know,” he replies. “Everything was running fine when she just quit.” He slides out of the skipper’s seat and I climb in. I turn the key. The engine cranks but doesn’t start. We click on the cabin lights over the table and the sink.

“Let’s unbutton her and take a look.” I have no idea what I’m looking for, but I’m hoping something will be obvious. While Danny rolls back the carpet and lifts the floorboards in the cabin to allow access to the engine, I call Don.

“Hey Marauder, Skookum Too. I have a problem here, Don.”

Steph, Don’s girlfriend and deckhand, comes back: “Hang on Skookum Too, I’ll wake him up.”

While we wait, Danny drops into the engine room and starts poking around with a flashlight.

“Check the fuel filter and lines,” I tell him. “And the solenoid.” This engine has a temperamental fuel system anyway, and when the device called the solenoid quits, the entire system becomes paralyzed. It has an indicator switch like a circuit breaker that lets us know when it has tripped, but it looks fine. There are no leaks, no loose wires, nothing that would indicate a problem. I turn the ignition to “On,” so the gauges come to life, but I don’t turn the engine over, not with Danny so near the fan belts. The needles all snap into place. Water temperature, amperes, everything looks normal.

“Skookum Too, what’s going on back there?” Don’s voice comes over the radio.

“Not sure. She just quit running. We’re looking at the engine now. As far as we can tell, everything looks fine, but she won’t start.”

“I’ll come back and give you a tow to the river,” he says. “Be there in about ten.”

We check battery cables, wires, circuit breakers, in-line fuses to the ignition, fuel lines. Everything checks out. But she won’t start. When Don arrives, we rig up a tow line from our bow to his stern, and he stretches the line slowly so it doesn’t part.

We are under way again, and I sit in the skipper’s seat steering so we don’t veer off to one side or the other with the swell behind us. The wind has backed off, but the seas are now six-to-eight-foot swells chasing us north. A big one lifts us, and when we ride down its back, the towline dips into it, slicing it like a knife.

When the wave catches and lifts the Marauder, the line parts with a thwaannngggg. Danny and I are on our feet in an instant. I steer the boat with the waves while he goes forward and brings the line back on board. The Marauder does the same and swings back around.

This time Don ties one of the old tires he uses for boat bumpers between the lines connecting our boats. The tire will hopefully act as a cushion and absorb some of the shock when the line gets pulled suddenly by the wave action. He ties the end to the line on his reel so the tow will be from the center of his stern, allowing him to steer better. Steph eases the boat forward as Don stands on deck directly behind the reel and watches.

Satisfied, he walks in the cabin and closes the door. Ten seconds later, the line parts between the tire and my bow, and the tire shoots forward like a loosed arrow. Danny and I both watch in the fading light as it rockets over the reel where Don was just standing, rope trailing behind it like the tail of a kite. It slams into the Marauder’s cabin door with enough force to bounce back over the reel to the picking deck.

“Jesus Christ!” I shout. If the line splits twenty seconds earlier, Don is dead or knocked overboard.

Steph goes out on deck and pulls in the line hanging behind the Marauder again, while Danny does the same on the bow of the Skookum. Meanwhile, Don and I discuss what to do on the radio.

“The boats are just too heavy in this swell,” he says. “I’ll try tying alongside.” Danny taps on the windshield and points to the bow cleat. As I look, he goes over to it and lifts the back end of it up. The bolts holding it are almost pulled completely through the wooden deck.

The Marauder approaches from our starboard side, the direction the swell is coming from. We get lines ready, and Don comes out of the cabin and goes up to his bridge for better visibility. Steph readies lines on the Marauder’s deck. The Skookum is full in the trough now, rolling sideways up and down the swells. We’re in no danger of capsizing, but the motion has the sides of the boat rising and falling several feet with each wave.

When the Marauder comes alongside, Danny tosses a stern line onto the Marauder, then hops over to the Marauder to tie off the stern. Steph, holding a line already tied to her midship cleat, straddles both the boats and loops the line around our cleat, then back to the Marauder’s. The Marauder is fiberglass, the Skookum wood. Just as she finishes tying the line to the cleat, the Marauder is lifted by a swell, and the four-inch-long bolts holding the cleat to the deck of the Skookum slide upward through the plank like it was butter.

Surprised at the force, I look at Steph, one leg on her boat, one leg on ours. I don’t even stop to think. I grab her by the front of her jacket, growl, “You’re with me!” and pull her on board as the wave rolls under us and boats surge apart. Don guns the engine so we don’t crash together on the next swell, and just like that, we’ve switched deckhands.

I make sure Steph is well on board before releasing her.

“You okay?” I ask. She nods. We’re both shaken by the unexpected display of violence. If she had fallen between the two heavy boats, she’d be crushed or drowned. We watch as Don turns the Marauder around to come alongside again, this time to trade people.

The boat pulls within a foot of us, and when he guns the engine in reverse, it stops dead. In an instant Steph and Danny switch positions. Don pulls away again, and he and Steph disappear into the cabin. Danny and I do the same.

“Well that was fun,” I say into the microphone. “What now?” I’m out of ideas and getting low on cleats.

“I don’t know,” Don says. “We can’t tow you, that’s obvious. There’s nothing left to tow with.”

“Let me call Ray,” I say. “Maybe he’ll have a suggestion.” Ray Landry is the cannery superintendent and an ex-engineer. He’s seen all sorts of predicaments during his years in the industry, and if anyone can puzzle out what our next move is, it’s him. I call him on the VHF and we discuss the possibility of rigging a cradle of rope under the boat and around the cabin to tow with, but that sounds iffy to me.

“All the tenders are filled with fish and boats in line to deliver more, Pat,” he answers when I ask if one of them could assist. “Besides, I don’t know what they can do, anyway. I could send the power skiff out, but we need to wait until the seas calm down.” The prospect of trying to set an anchor while loaded, adrift and without power doesn’t seem like a good plan at all. It’s completely dark now, and the wind and tide are pushing us toward Salamatof beach north of the river mouth, where the shoreline is riddled with rocks.

“Let me see if we can figure out what’s wrong with the engine one more time, Ray. I’ll get back to you.” Don comes on the other radio.

“I’ll stand by here until you figure out what’s going on, Pat.” I know that’s a sacrifice. It’s late, and we’re the only ones out here. We’re going to be the last boats in the river, and even if we do arrive at a solution, it’s going to be hours before we get any sleep. I shake my head at my good fortune to have two brothers like Don and Dean as friends.

“Thanks Don. You’ll be the first to know if I find anything.”

Waiting to Deliver

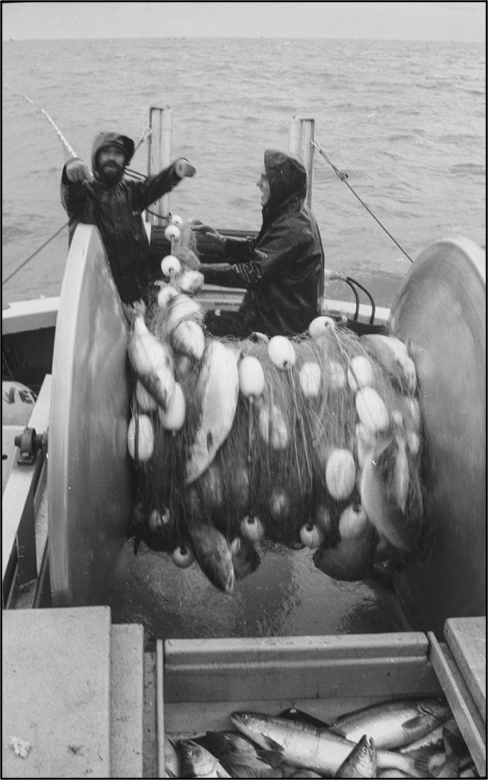

On the good day

when boats return home

low in the water, holds full,

nets wrapped around salmon

rolled on the reel,

after picking half the net,

and laying it back out

while the fish keep hitting,

then running to the other end

and doing it again, all day long–

no time for breaks, a sandwich

or even water, your face, beard

and glasses streaked black by gurry,

dotted white with scales, back

aching, fingers and wrists sore,

you find energy reserves –

threads of adrenaline buried deep

sustain you ‘til you’ve made the run home

and toss a line to the boat you tie behind,

the last of a dozen hanging off the port stern

next to a matching group tied

to the starboard side of the tender

taking fish anchored in the middle

of the river. This day of donkeywork,

this day of absolution isn’t over,

won’t be for hours. At the back

of the queue, you know you’ll be here

past dinner, past dark, maybe past dawn.

You’ll eat a baked potato and a red salmon

garnished with lemon, onion and butter

less than two hours from the time

you plucked it alive from the sea.

You’ll wash it down with a cold beer

from the cooler, watch the sunset

and think how this is the best,

most complete life you can imagine.

Salt air cools as shadows lengthen

and the water changes from blue to black.

You trade bunk time with your deckhand

and fall asleep before your head

hits the pillow. The smack of a boathook

on the bow wakes you both as the next

boat in line cuts you all loose to go deliver

and those of you still tethered together

like a serpent in the glare of arc lights

work to move up– fighting the river’s flow,

pulled and yanked off-course by boats

fore and aft, bumping throttles forward,

neutral, reverse, trying not to ram the one

ahead of you, hoping the one behind you

does the same. Your deckhand fends off

as you swing too close to the vessels sleeping

to starboard, until the lead boat tosses

a line around the tender’s cleat again

and you all slide back in the current like a sigh.

Engine after engine goes silent. Lines creak

around the cleats as they stretch taut.

Your crew slips into the bunk while you

settle back in the skipper’s chair,

light a smoke and sip a cold cup of coffee.

You’re still waiting. Waiting to deliver.