Alaska’s Bering Sea crabbers are reeling from the devastating news that all major crab stocks are down substantially, based on summer survey results, and the Bristol Bay red king crab fishery will be closed for the first time in more than 25 years.

That stock has been on a steady decline for several years, and the 2020 harvest dwindled to just 2.6 million pounds.

Most shocking was the drastic turn-around for snow crab stocks, which in 2018 showed a 60 percent boost in market-sized male crabs (the only ones retained for sale) and nearly the same for females. That year’s survey was documented as “one of the largest snow crab recruitment events biologists have ever seen,” said Dr. Bob Foy, director of the North Pacific Fishery Management Council’s Crab Plan Team.

Again in 2019, the “very strong” snow crab biomass was projected at over 610 million pounds, and the catch was set at a conservative 45 million pounds for the 2020 fishery. No Bering Sea crab surveys were done that year because of the covid pandemic, but the 2021 results indicated the numbers of mature male snow crab had plummeted by 55 percent.

The stock “seems to have disappeared or moved elsewhere,” said Jamie Goen, executive director of the trade group Alaska Bering Sea Crabbers. The snow crab catch for the upcoming season could be down by 70 percent and the stock could be classified as “over-fished,” she said, adding that no decisions will be made until the data undergo more scrutiny by plan team and Council scientists.

The crabbers want “bold action” from federal fishery managers. They are calling on the North Pacific Fishery Management Council and NMFS to conserve crab habitat and spawning grounds highlighted by scientists over 10 years ago with little resulting action.

The crabbers also want managers “to create meaningful incentives to reduce crab bycatch in other fishing sectors, to reduce fishing impacts on molting and mating crab, and to estimate unaccounted for bycatch from unobserved fishing mortality from bottom and pelagic (midwater) trawl nets, as well as pot and longline gears.”

Boats fishing the Bering Sea are required to have 100 percent observer coverage to track what is retained and what is tossed over the side, but it’s what is not observed that most concerns the crabbers. And what goes unseen is not factored into stock or bycatch assessments.

The Magnuson-Stevens Act, the primary law governing marine fisheries management in federal waters (from three to 200 miles out), defines unobserved mortality as “fishing mortality due to an encounter with fishing gear that does not result in capture of fish.”

In a February letter to the North Pacific council, the crabbers highlighted studies showing “that 95-99 percent of crab in the path of trawl gear go under the footrope escaping capture, and some portion of those likely die after contact with the fishing gear. Given this number compared to what is observed as bycatch, the potential for unobserved mortality of crab could be millions of additional pounds of dead crab bycatch.”

A February report by council scientists, which (unsuccessfully) proposed an amendment to the management plan for crab bycatch in the Bering Sea groundfish trawl fisheries, stated: “Crab may actively escape capture from trawl gear, as they can slip under the trawl itself, or over the sweeps, but the damage from the gear results in mortality or delayed mortality due to injuries. The potential for unobserved mortality of crabs that encounter bottom trawls but are not captured has long been a concern for the management of groundfish fisheries in the Bering Sea.” (Witherell and Pautzke, 1997; Witherell and Woodby, 2005).

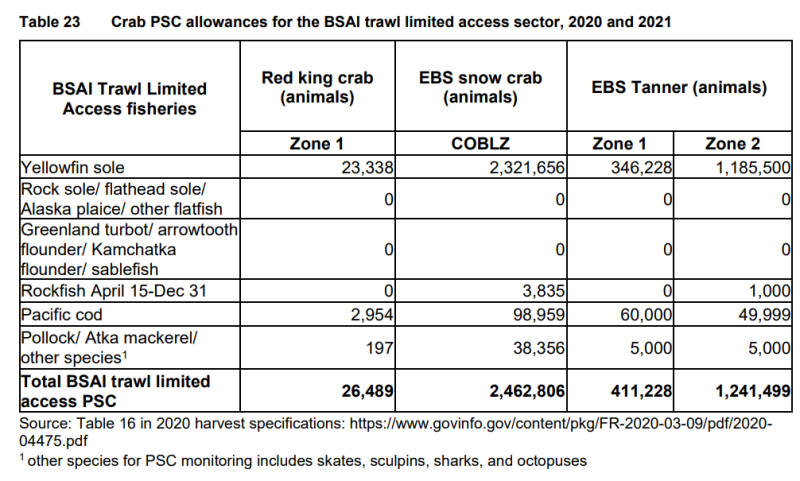

The report said that “the majority of trawl caught crab PSC (prohibited species catch) occurs when vessels are targeting yellowfin sole. This is the case across all crab species.”

Yellowfin sole is one of six groundfish species targeted by a cooperative of 18-20 bottom trawlers called the Amendment 80 fleet that includes seven vessels owned by Alaska Native Community Development Quota groups. No CDQ trawl vessels have made shoreside deliveries in Alaska over the past 10 years.

The A80 boats, all of which are home-ported in Seattle, range in length from 200 to more than 300 feet and contain processing facilities. They usually fish from late January through the fall, and last year caught nearly 300 million pounds of yellowfin sole valued at $.09 per pound.

Each of the A80 boats employs six fishing crew, approximately 24 processing workers and seven other staff, including officers, engineers and cooks. The council report said 69 percent of the crew (not including processing workers) reside in or near Seattle. Direct wages paid during 2018 were $46 million, and $52 million to the state of Washington, overall. In contrast, Alaska residents accounted for 3 to 8 percent of A80 crews and took home $2 million in direct wages.

The Crab Plan Team meets Sept. 13-16 to discuss the Bering Sea crab stock assessments. Catches for the 2021-22 season will be announced prior to the Oct. 15 start. Reducing crab bycatch is not on the agenda.

The council meets via web conference from Oct. 6-10, when it will set preliminary catch and bycatch levels for 2022.

Meanwhile, in Southeast Alaska, Dungeness crabbers wrapped up an “average” season for a 2-1/2-month summer fishery that ended in mid-August.

Preliminary numbers indicate the catch came in at half of last summer’s level, said Adam Messmer, Alaska Department of Fish and Game assistant manager for the region.

“We ended up with just over 3 million pounds this season, which is right around our 10-year average. Last year was our second biggest year ever. We were kind of expecting a little bit more than what we caught this year. But we had a quite a bit of soft shell crab (newly molted) at the beginning of the summer. That accounts for the missed poundage,” he said.

The 2020 Dungie catch of 6 million pounds was valued at nearly $10 million at the docks.

Despite a lower catch this summer, the harvest of the two-pounders was worth much more to the fleet of 205 permit holders.

“Yep, it was our highest price ever, averaging $4.27 per pound. That came out to almost a $13 million fishery. So that pencils out to about $63,000 per permit,” Messmer added.

Southeast crabbers get another go when the Dungeness fishery reopens on Oct. 1.

Dropping pots for Dungeness is ongoing around Kodiak and the Westward region until the end of October. Around 1.5 million pounds is likely to be the tally for 20 Kodiak boats, down about 1 million from last year. But the outlook is fairly optimistic said Nat Nichols, area manager for ADF&G.

“Here in Kodiak, that makes three seasons in a row of over a million pounds. And I’ve heard some reports that there’s a lot of crab measuring going on and there’s a lot of crab that are just a little bit short of the stick. So that sort of gives optimism for next year,” he said, adding that fishermen also are encountering a lot of soft shell crab that are returned to the water.

More than 415,000 pounds of Dungies have been hauled up at Chignik, and Alaska Peninsula fishermen are having the region’s best catches, now at 1.3 million pounds. The Westward price is $4.35 per pound on average.