Ask 10 people to define a sustainable fishery, and you're likely to get 10 different answers. Some define it as one that is harvested at a sustainable rate, such that the fish population does not decline over time as a result of fishing practices. How lovely would it be if we understood so much about the oceans that we could actually tell with little doubt when the effects of biomass change were strictly the result of fishing or some other factor?

When it comes to U.S. fisheries, overall we're doing well, despite the lack of a consistent definition of what exactly it is that we're striving to achieve. But where we're failing, we're failing in a tremendously damaging way.

The Center for Sustainable Fisheries — led by Dr. Brian Rothschild, former Rep. Barney Frank and former New Bedford, Mass., Mayor Scott Lang — is seeking to reverse those damages by rewriting the National Standards in the Magnuson-Stevens Act. The aim is to focus on improving data and finding a better balance between sustaining fish populations and the communities that depend on those resources.

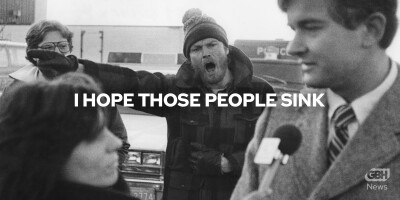

In New England, entire communities of fishermen are on the precipice (or beyond) as a result of poorly managed groundfish and shrimp stocks. People who don't understand all the intricacies of the groundfish fishery like to blame the fishermen for overfishing and call it a day.

But the fishery has been federally managed for decades, and in those decades, it has declined steadily. Also in those decades, many other fisheries have recovered from population depletion — as a result of management changes, habitat improvement, climatic shifts and in some cases dumb luck.

New England groundfish stands as an icon for fisheries management failures. We clearly did not fully understand the effects of the fleets foreign trawlers on our stocks before we kicked them to the curb nearly 40 years ago. We clearly did not understand the effects of improved fishing technology and federally incentivized fish-boat-building loans that encouraged any Tom, Dick or Harry to build a boat and go fishing. We most certainly did not understand the nature of spiny dogfish — cod's top competitor for resources — when we protected it from so-called overfishing and sent its numbers soaring to unmanageable highs, meanwhile strangling the market for the now Marine Stewardship Council-certified fishery.

We did not understand how significantly any one of these factors would hamstring the New England groundfish fishery. And now we're asking entire fishing communities to pay for our failures by effectively shutting down their source of livelihood. And why? Because we have clear data that show

s the state of the stocks? No, that we don't have. If we did, the shuttering would be a bitter but tolerable pill to swallow. All we have is our best guess and a draconian federal law that says since the management system didn't find a way to turn around decades of damage in the span of 10 years, then the fishing communities have to pay for the lack of results.

Those same communities that followed the rules year in and year out, watching the slow contrition with little source of hope, now find that they're paying a terrible price despite their efforts to do the right thing.

And yet, even with a declared federal disaster, there is little sympathy for the region's fishermen. Many of them have relied on the winter Northern shrimp fishery to make up a little for the lack of access to groundfish. But this year, that fishery has been shut down entirely, largely because warming waters have hampered reproduction.

Sustaining New England's historic fishing communities will have to come from the first definition of the word: capable of being supported or upheld, as by having its weight borne from below.

In times of great need, we have to support our fishing communities, either from above or below. I hope efforts to sustain all of America's fishing fleets will lead to some changes in the Magnuson-Stevens Act that can strike a better balance and establish the groundwork for a truly sustainable industry.