Seafood fraud and mislabeled seafood is a permanent topic in the sustainable fisheries space and has been driving the demands for product traceability. Since 2011, Oceana has led the discourse on fish fraud by publishing sixteen reports on the subject.

Oceana Canada’s 2018 report exposed some important shortcomings in the Canadian seafood system and offered constructive, achievable mandates for reducing seafood fraud domestically, but the study collected data from a biased sample and only presented results that supported a narrative of rampant fraudulence.

Oceana collects seafood samples at restaurants and retail outlets, DNA tests them, then matches the DNA results to government labeling guidelines. The sampling focused specifically on cod, halibut, snapper, tuna, salmon and sole because these species historically, “have the highest rates of species substitution.” This nonrandom sampling is consistent with previous seafood fraud studies from Oceana.

Of the 382 seafood samples tested in Canada, 168 (44 percent) were found to be mislabeled.

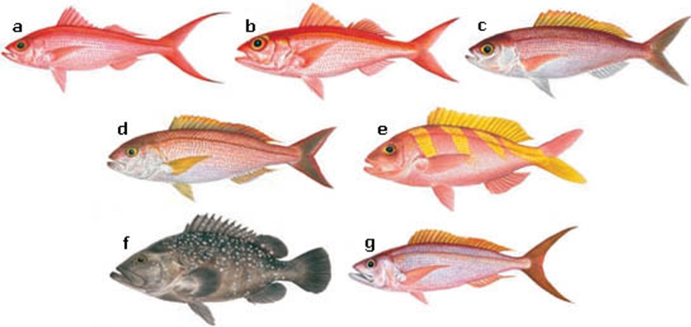

None of the red snapper (Lutjanus campechanus), yellowtail or butterfish tested was appropriately labeled. Tuna was mislabeled 41 percent of the time, halibut 34 percent, cod 32 percent and salmon 18 percent.

Fundamental to the interpretation of the Oceana Canada 2018 study’s results is the understanding that the samples were selected to find fraud, not to measure the actual extent of fraud across the entire seafood supply chain. Oceana disclosed this in the report. However the press release it issued for this report, and subsequent headlines from other news sources, such as “At least one quarter of the seafood you buy is a lie” from the site IFL Science, created a different narrative.

Aside from the sampling criticisms, the analysis of specific species was especially flawed.

For example, there are more than 200 distinct species of “snapper” in the Canadian Food Inspection Agency’s Fish List, many of which have red skin; however only Lutjanus campechanus is considered to be the true “red snapper” by the agency’s standards. Should we expect chefs operating in their second language (a high rate of red snapper mislabeling was reported in sushi restaurants, for example) to understand such a nuanced species category? There is a difference between red snapper mislabeled as other species of snapper, and tilapia or rockfish substituted as snapper. But Oceana made no distinction and instead claimed 100 percent of all snapper tested was fraudulent.

Yellowtail was another species never labeled correctly according to this study. But unlike red snapper, every yellowtail sample tested was actually Japanese amberjack. This is a head scratcher, because everyone in the seafood industry understands these two names are accepted synonyms in the market, but Oceana completely ignored that reality.

“Sea bass” is another species commonly mislabeled according to this study, but at no point did Oceana establish which species of sea bass they were expecting to find: white sea bass (Atractoscion nobilis), black sea bass (Centropristis striata), Chilean sea bass (Patagonian toothfish or Dissostichus eleginoides), Mediterranean sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax). This study was extremely specific about what constituted yellowtail, but was extremely vague about what constituted sea bass.

Oceana’s conclusions did correctly acknowledge that seafood fraud not only hurts consumers, but law-abiding fishermen, processors and suppliers who are not collecting greater profits by mislabeling cheap species. Economic incentives to mislabel seafood are strong given rising seafood costs and the realities of a competitive foodservice industry.

Unfortunately, the health implications of mislabeled seafood were not as well argued.

Health analysis mostly focused on a misconception about escolar, labeled as “butterfish,” and its reputation as the “laxative fish.” This species can cause gastrointestinal problems when consumed in large amounts, but the United States Food and Drug Administration rescinded a ban on the importation of the species in the 1992, concluding it was not a health risk. Since then it has appeared on some of the most celebrated fine dining menus in the world, proving its value when properly prepared.

This study from Oceana Canada, and all other reports of seafood fraud, so highlight the mislabeling of some species. Sadly though, this study (and others like it) fail to provide representative results.

The samples tested are not representative of actual seafood consumption across Canada such that the true scope of the issue is impossible to determine. This study will serve to frighten consumers — pushing them away from seafood and toward more carbon-taxing land-based animal proteins — confuse policy makers, and unfairly implicate responsible actors in the seafood industry. Another flashy, fearmongering headline does raise Oceana’s profile, however. It is a shame Oceana focuses its considerable power and resources (in the marine conservation world) on issues that should take a back seat to much more pressing ocean threats.

The full version of this article was originally published on SustainableFisheries-UW.org. Follow Sustainable Fisheries UW on Twitter, Facebook or subscribe to their mailing list.