Unfortunately, National Fisherman didn’t run a Crew Shots issue back in the ‘80s, so reading through the archives to put together the Fishing Back When section wasn’t as fun as looking through the new issue.

Instead of flipping through the fun photos from crews across the country, I stumbled upon a story in the January 1986 issue that focused on Florida’s struggling calico scallop fleet.

The fleet was dealing with a fluctuating market, unpredictable production and the regular fish politics, but they were also plagued by accidents at sea. In the first seven months of 1985, 13 boats in the fleet capsized. Stability issues ran rampant.

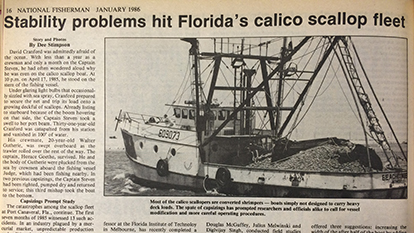

A team from the Florida Institute of Technology completed a two-year study on the fleet to figure out what was happening on these boats. One of the problems was that most of the boats used in the central Florida scallop fleet were old shrimp trawlers purchased from Gulf shrimpers when the industry was critically depressed. Those vessels were safe for shrimping because shrimp would’ve been stored below deck. The hulls hadn’t been modified to take on the large deckloads that came with scalloping.

Shoreside facilities required the catch to be carried on deck for off-loading and efforts to find an alternative means had not been successful.

These scallopers filled the decks, too. Most captains and crew said excessive loads were necessary to make any money. It turns out that these vessels were bringing in plenty of sand with them as well, adding to the weight on deck.

“It’s overfishing,” said Eddie Moore, a vessel owner with eight years of experience in the industry. “If you bring up sand, you just have to limit your load, like it or not.”

In the end, experts decided that human error was the source of the problems. There wasn’t anything happening that wasn’t avoidable.

“Nowadays, these guys punch on the autopilot,” said Moore. “That’s what I see as the main cause for more accidents.”

In Washington, D.C., U.S. Coast Guard Capt. Gordon Pliche, manager of the Fishing Vessel Safety Task Force, agreed that the men on the boat are ultimately responsible.

“The situation is that many, many operators of these vessels don’t even know the most basic rules of the road as they apply to maritime operations,” he said. They’re great at catching scallops; it’s just that the people using the boats do not seem to understand the way they must use a vessel that hasn’t been designed for their fishery.”

Using a vessel designed for another fishery could save you a buck or two, but you have to know how to handle it. In this situation, men were pushing their boats beyond limits in a very dangerous environment.

The study led to new Coast Guard guidelines and education programs that corrected the stability issues in the long run.

What this fleet learned the hard way about stability has likely saved fishing lives in the last 30 years.