This International Fisherwomen’s Day, I’m celebrating the origin of set netting in Bristol Bay — born of women’s ingenuity and their unique experiences in fisheries.

I was taken out to our set net site to experience the work of fishing long before I was old enough to officially join my family in it. Around the age of five, I remember sitting with my great-grandfather in a small plastic dinghy, just big enough to hold us and the salmon my family was picking from our gillnet. He pulled us along the anchor line of our set net site on a sunny day with gentle water. My family waded nearby, passing salmon from the net to the boat to keep them contained. I felt the power of the fish still alive as they thrashed against the air and my rain gear. Other times, I would clumsily try to walk in the mud uncovered as the tide receded — and would often walk right out of my boots.

By age 10, I was deemed ready to work alongside my family tending our fishing sites — the same age my sisters and our mother had started. Our “Young Grandma” Anisha fished a site until she retired, and our great-grandmother, Anna Chukan — whom we lovingly called Umma — did too.

November 5 marks the first-ever International Fisherwomen’s Day, convened by the World Forum of Fisher Peoples, representing more than 10 million traditional, artisanal, and small-scale seafood harvesters worldwide. In honor of the day, I’d like to share some history of a fishery dear to my heart: the set net fishery for sockeye salmon in Bristol Bay, Alaska. Set netting means anchoring a stationary net on the shore so fish swim into it with the tide or current. I am the fourth generation in my family to practice this form of fishing in Bristol Bay, and my children are the fifth.

There was a time when set netting was referred to as work for “women and handicaps,” according to the documentary Making Waves in Bristol Bay. I suppose the men who were drift fishing in double-ended sailboats from the inception of the Bristol Bay commercial fishery in 1886 felt the need to distinguish themselves somehow. This description reflects the problematic ways women and their labor in fisheries were viewed at the time. Today, set netting is more physically demanding than drift fishing, since the drift fleet converted to powerboats in 1951 and has since evolved to use hydraulics that spool nets onto reels as crews pick salmon from the gear on deck.

No rule makes set netting exclusive to women, and many men now participate in the Bristol Bay set net fishery. But it is a form born of women’s ingenuity and experience — balancing the responsibilities of feeding their families, tending the home, and managing all that happens on land while also participating in the catch. It is this incredible fortitude and fierceness that I celebrate on International Fisherwomen’s Day. Women deserve recognition for their presence and contributions to fisheries worldwide, rather than being demeaned when their expertise and labor are acknowledged.

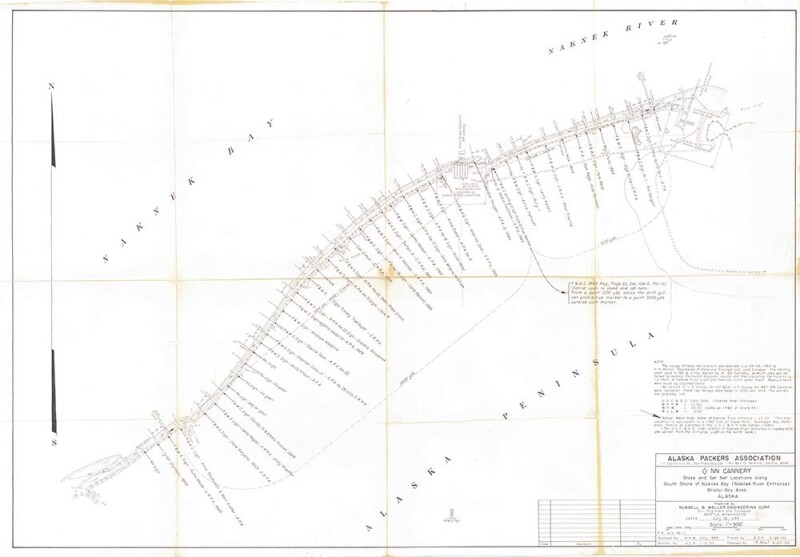

Every summer, I fish a site on the north bank of the Naknek River that was staked out by my great-grandfather, Paul Chukan, next to three sites claimed by three sisters when he transitioned from drift fishing in a sailboat. Legend has it that women invented the technique of set netting on the south side of the Naknek River. What I know of this origin story helps paint a picture of the necessity that led to its creation.

The first commercial fishermen in Bristol Bay were recent immigrants — Swedish and Italian men recruited to fish company sailboats because they came from fishing cultures. Indigenous people of Bristol Bay were excluded from fishing for the canneries but found employment on the cutting and slime lines. Non-Native local men joined the fleet soon after the fishery began, but it wasn’t until the 1920s that local Indigenous men were allowed to fish company boats. I believe my grandfather was one of the first to request that permission. When the local fishermen were towed out on Monday mornings and released to fish in the Bay until their return Saturday night, the women were left to provide for their families in every way.

LaRece Egli, director of the Bristol Bay Historical Society Museum, began preservation work on the south side of the Naknek River to recognize the 130-year-old NN Cannery on the National Register of Historic Places. She shared with me that, when the men were out fishing, the local women left behind needed to catch fish to feed their families. To do this, they took old pieces of gillnet and laid them perpendicular to the shoreline so that salmon would catch as the tide came in. They placed these nets close to the riverbanks, where they could easily bring the fish home to cut, preserve, and prepare for food. I had never heard this story until LaRece told me — she herself had learned it from a woman in South Naknek. I can only imagine how set netting evolved from there, but those women set a precedent that now represents a vital part of the Bristol Bay sockeye salmon commercial fishery.

Today, many local women carry the set net fishery forward after multiple generations before them. Women have also long been part of the Bristol Bay drift fleet—some captaining their own boats, and others running all-women crews. I know women captains who stepped away to let their husbands run their boats when they had children and never returned to the helm. Motherhood makes it difficult to fish; I missed a few seasons myself because of pregnancy and nursing. Being a mother brings an expectation of caretaking, even when you’re out fishing and doing all the physical work it takes to bring in the catch.

I recall the dynamic when my mother was still set netting and my father was out for the season on his drift boat. Members of his radio group would call to ask my mom for rides to or from their boats in our skiff, to take them to the airport, or to house and feed them. This wasn’t usually a hardship, but when the fish were running hard and we were trying to rest and eat between heavy tides, it wasn’t fun to have someone knocking on the door to use the phone or radio. My mom’s sleep was always compromised. She supported my dad’s fishing and saw it as their shared work.

When I fish, I don’t often think about my gender. I grew up watching my mother move between her fishing work and the unseen labor at home that made it all possible, so it felt like part of fishing life before I ever named it as gendered. Fishing is a raw act that lifts nature’s power above our individual needs—we face something so much larger than ourselves. But when the season ends, I love returning to my more feminine side, a reminder of all that I contain.

On this inaugural International Fisherwomen’s Day, I invite us all to think of the women who too often go unrecognized for their contributions to fishing. Even if they never live their fish lives on the water, their labor, resilience, and creativity sustain the work—on the docks, on the cutting lines, in the markets, and at home. I celebrate all that is contained within us—whether we are women who make fishing possible by being supportive mothers, wives, and friends, or whether we are out there ourselves, juggling the many expectations that still cling to outdated notions of women’s work.

Melanie Brown fishes Bristol Bay with her children on a set-net site that her great-grandfather Paul Chukan staked out on the north side of the Naknek River. She is a member of the Coordinating Committee of the World Forum of Fisher People and attended the first Global Fisherwomen’s Assembly this August in Hat Yai, Thailand.