Below is an addendum to the original February 3, 2025, submission to National Fisherman, “110 years of halibut and heritage: The Legacy of the FVOA.” The FVOA developed this with Arni Thomson while awaiting the publication schedule from the NF Editorial Team.

The beginning of the Pacific Halibut Fishery in the late nineteenth century was a period of discovery for the industry, of exploring markets and integrating new technology that would propel development of an industry. After the turn of the century, according to Bell, the fishery enjoyed a profitable fifteen-year period of expansion with an almost geometric rise in total catch in the first seven of those years.

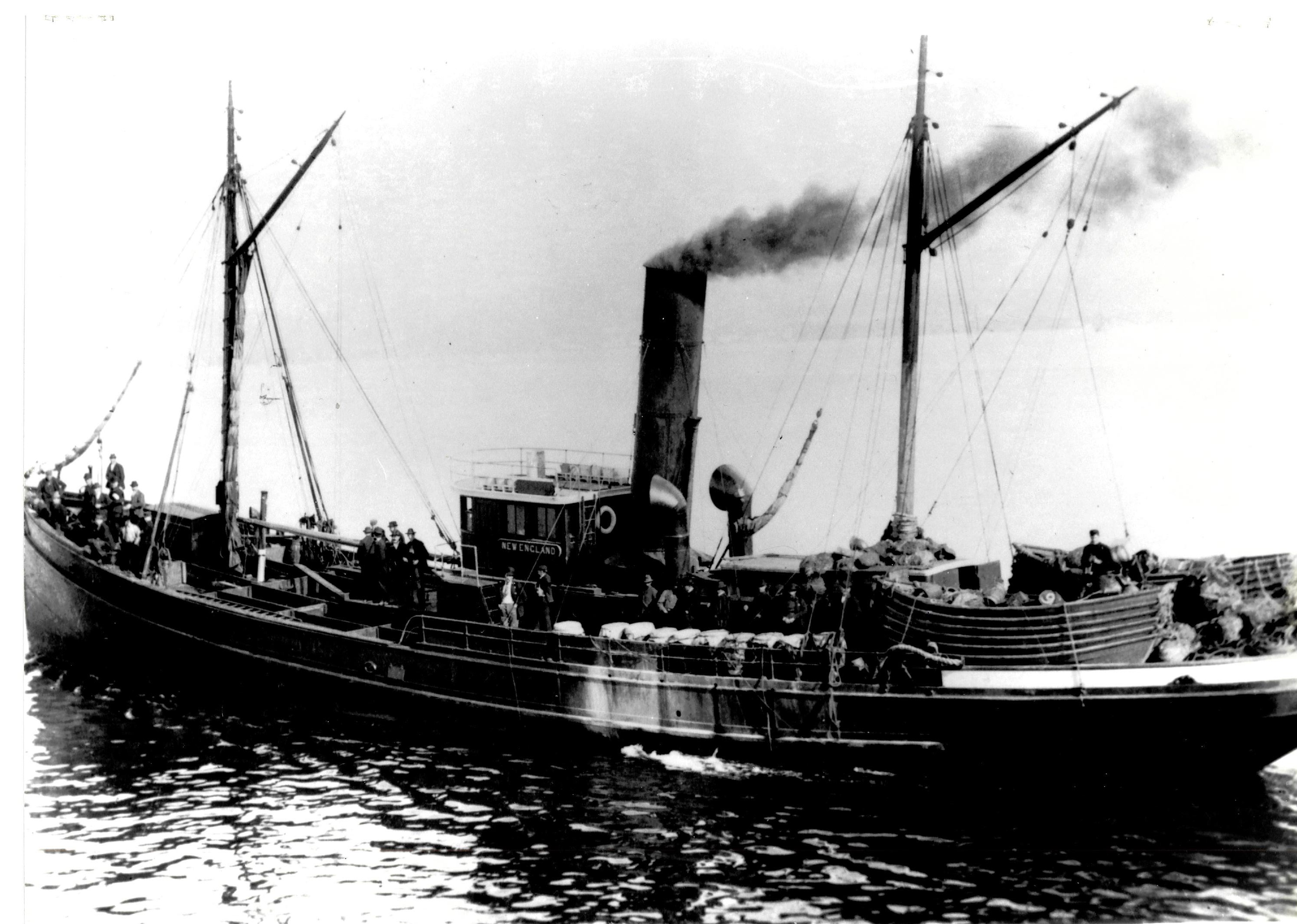

While prices were low compared to present-day standards, only two cents per pound in Seattle in 1902, rising to four cents by 1904, net returns in stable dollars were high during most of the first fifteen years of the 20th century. Earnings were fueled by internal combustion engines and new vessel design, first the custom-built steamers, then the advent of the rugged halibut schooners and the development of cold storages in Seattle, Tacoma, Vancouver, and Prince Rupert. Also, more firms entered the industry both in Canada and the United States.

At the time of formation of the Pacific Coast Fishermens Association/FVOA in 1914-1915, marketing problems were developing, brought about by the rapid increase in production and other dislocations partly due to the onset of World War I in Europe. Prices had remained level at about 5 cents per pound since 1907, but costs on the large steamers had sharply increased. In 1916, four of the largest steamers were wrecked and could not be replaced. Shipyard costs were high and shipyards were preoccupied with cargo-vessel construction to offset massive Allied losses to German U boats in the Atlantic. Shipyards were building three cargo ships per day at the peak of production in 1917 – 1919, or 100 warships per month. They had also begun building a fleet of sixteen revolutionary “dreadnaught” class battleships to keep pace with British and German navies. Manpower for halibut crews became scarce with the advent of conscription in the U.S. in 1917.

The growing fleet of independently owned, owner-operated vessels with smaller crews prospered during the later years of World War I, 1917-1919. Prices paid in Seattle for number one halibut had doubled by 1916 to ten cents per pound and reached sixteen cents by 1920; demand for all fish was high; prolific new halibut grounds west of Cape Spencer provided a profitable winter fishery for larger halibut vessels; and Prince Rupert was opened to landings by U.S. vessels in 1915 for shipment in bond on the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway through Canada to the eastern United States markets. During this period, many crew members accumulated earnings that would lead to ownership shares in new or older vessels in the early 1920s.

Another of the positive results of the war was the closer cooperation in fisheries matters between the U.S. and Canada than had prevailed during the previous 100 years. Measures were enacted and restrictions were removed in both countries to facilitate the war effort. Discussions of a joint halibut fisheries commission were also undertaken at this time.

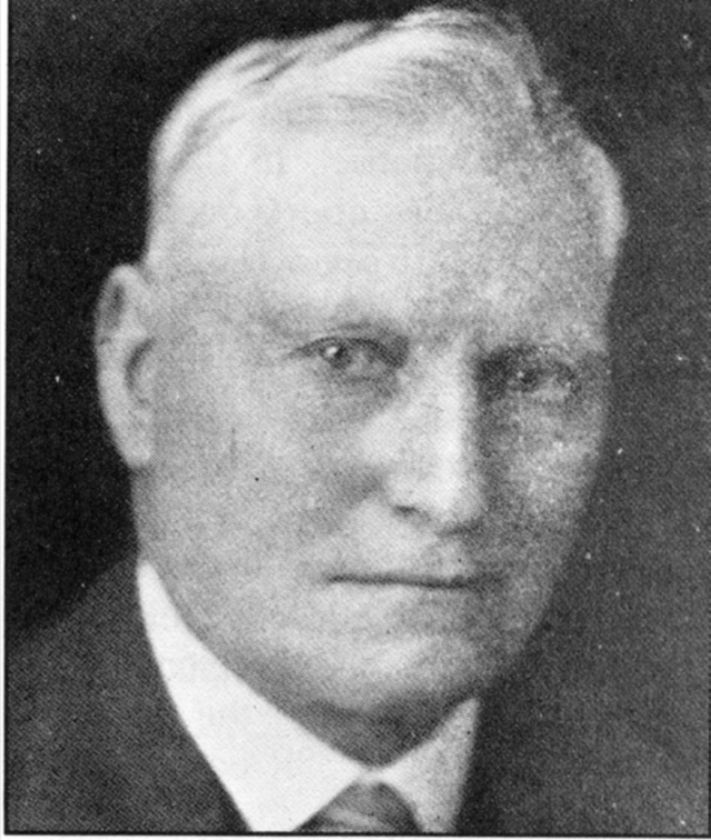

The impact of the postwar depression of 1921-1922 with a temporary price decline was partly offset by the installation of the more economical diesel engine in many of the vessels. Halibut prices soon recovered to the pre-depression fifteen-cent level, and there was a near-boom in vessel building, particularly the schooners. Ship chandlers to the fishing industry supplemented the savings of former crew members to provide some of the construction capital. The decade of the 1920s was another period of expansion in the fishery as it was for the whole North American economy. However, prices paid for first-class halibut remained at an even level of sixteen to eighteen cents per pound in Seattle from 1923 to 1929. It was at this time that Harold Lokken began his fifty-two year tenure with the FVOA. By the end of the decade, the “cost/price squeeze” began to be serious as fleet operating costs had steadily risen.

With the onset of the Great Depression following the crash on Black Friday on October 25, 1929, halibut prices, like most other commodities, began to decline drastically, sixty-two per cent between 1929 and 1932. The halibut industry would have to deal with this on its own in its customary independent and resolute manner without government support. (Bell, p. 119) The economic depression of the 1930s was one of the most critical problems the halibut fleets of the U.S. and Canada had to face since their beginning in 1888. Although the halibut stocks had ceased to decline due to economic conditions being so poor, it caused the fleet to reduce fishing, and subsequently, due to controls of the newly sanctioned Halibut Commission, they were still at very low levels. Market prices had plummeted. These two factors, low stocks involving smaller trips, along with low prices, spelled economic ruin for the fleet with owners unable to meet their fixed costs, and loss of jobs for the crewmen. In the early 1930s, all factors were negative. Prices were low, fish scarce and there were no new grounds to exploit. Options started to be discussed by the trade organizations, FVOA and the Deep Sea Union in Seattle and in Canada by the United Fishermen’s and Allied Workers Union. It became very clear that fisheries would receive little economic assistance from government in times of stress. Bell noted that “it might be said that the Pacific halibut fishery had survived not because of, but in spite of, many actions of the federal bureaucracies down through the years.” (p. 139).

In 1932, the FVOA and the Deep Sea Fishermen's Union wasted no time forming the Halibut Control Board, an unincorporated voluntary committee whose immediate purpose was to provide for the more orderly flow of the annual catch limits of halibut set by the Halibut Commission. The Commission, as a public body, could not, under the convention, participate in any part of the program. However, statistical and other analyses of various measures were available to the fleet. The whole program, as it was to develop beginning in 1933, was aimed at reducing production and came to be known as “curtailment.” The program came to the attention of the Department of Justice in the U.S. looking for restraint of trade under the Sherman Act, but nothing surfaced during its tenure from 1932 through 1942. It became clear that the only real restraints on the fishery and on production were those imposed under law by the Halibut Commission. This included setting catch limits, closed seasons and the application of other restrictions in accord with the Halibut conventions. The fleet believed that price fluctuations could be reduced and the general level of prices improved if the bunching of landings could be reduced, particularly at the beginning of the season. In addition, if the total catch could be spread more evenly over about a nine-month season. Another different objective was to secure a more even distribution of the catch between vessels.

In order to reduce the bunching of landings, the U.S. fleet devided into two alphabet-based groups, depending on vessel names. The first half commenced to fish on the opening day of the season and the second half, seven days later. To further spread the catch and slow down the rate of landings, beginning in 1932 the vessels were required by their control board to undergo a number of between-trip lay-ins of varying lengths. All vessels were required to take two six day lay-ins in March to mid-April, fourteen days between April 15 and June 15 and a seven-day lay-in in September.

The Canadian fleet, mainly centered in Prince Rupert at the time and some of the Alaskan vessels did not subscribe to the 1932 program. The Canadian share in the fishery then was very low at fifteen percent of the total Pacific coast catch and in decline, undergoing about a ten percent drop annually from 1928 to 1932. Therefore their lack of adherence to the program from 1932 to 1934 had little effect on the rate of landings. Very low prices caused many Canadian vessels to switch to salmon trolling. Whether the foregoing voluntary measures were effective is a moot point, according to Bell, as there is no basis upon which to make a valid judgment. However, prices might have been much lower without the program.

In 1933 two new components were added to the fleet’s program---a maximum catch per crew member per trip, and advance schedules of arrival dates set for each vessel. The limit of catch-per crew member was expected to reduce the rate of landings and also to improve quality by the shorter and smaller trips. The advance assignment of landings was designed to keep weekly landings in the then major halibut ports of Seattle, Prince Rupert and Ketchikan in balance with market demands and also to improve quality by the shorter and probably smaller trips. In addition to these voluntary measures the fleet precedentially set the total catch to thirty-five million pounds, which was eleven million pounds below the Halibut Commission’s regulations. The goal was to hold prices to a minimum of six cents per pound for No. 1 fish and four cents for No. 2s. The projected price levels were achieved in the open market without any self-imposed reduction in the total annual catch allowed by the commission and thus avoided a U.S. Department of Justice inquiry.

The catch limits per-man-per-trip in Area 2 covering British Columbia and southward, including California were at 3,000 pounds and 4,000 pounds in Area 3 the Gulf of Alaska including the offshore Kodiak and South Peninsula grounds. They were determined by the Halibut Commission at the request of the control board, based on catch records from 1932. In addition to these primary features of the voluntary control program, there were numerous administrative provisions in the plan designed to make the rather complex program functionable and enforceable.

During this time the world-wide Great Depression was at its worst. In the United States economic conditions had reached a stage of chaos, with numerous bank closures, excessive deflation of all values, widespread foreclosures on mortgages and other debts and nationwide unemployment rising to dangerous levels. Drastic measures were undertaken at the federal level, including the establishment of numerous federal corporations designed to stabilize the economy along with the temporary bank holiday to avert a catastrophic panic. Fisheries came under the jurisdiction of the newly formed National (Industrial) Recovery Administration (NRA) and the Agricultural Adjustment Administration (AAA). Fisheries were shuttled back and forth between the two agencies but usually ended up under the NRA.

The FVOA prepared a Divisional Code of Fair Competition to be implemented and given the force of law under the newly formed NRA of 1933. The plan included two basic provisions, catch-per-man-per-trip for the two major areas and staggered departures at the beginning of the season to even out landings and it omitted pre-assignment of landings that had been in the 1933 voluntary plan. There was general agreement among the fleet in support of the code. Despite practical unanimity among the fleet in favor of the code and the proven feasibility as indicated by the results in 1932 and 1933, the NRA failed to put it in force. The fleet, however, put essentially the same plan into effect in 1934 on a voluntary basis that was in the proposed code.

Although the program lacked the force of law it would have possessed under the NRA, it remained free from the inevitable interference of a cumbersome, inflexible, and frequently inefficient bureaucracy. The 1935 Control Program reduced the per-man-per-trip catches at 2,800 pounds per man in Area 2 and 3,500 pounds per man in Area 3 where it remained through 1941. In 1942 all control by the fleet in Area 3, the Gulf of Alaska, was terminated as of June 29 and in Area 2 by the end of the year. Due to wartime conditions, the United States Navy wished the fishing season to be closed as soon as possible and there was increasing difficulty in maintaining voluntary compliance.

In 1934, the Canadian fleet participated in the program on a reduced scale. Between-trip tie-ups were four to five days in length compared to the ten day and longer tie-ups for the American vessels. The reduced length of the tie-ups for the Canadians was predicated on the basis that the Canadian fleet was in a more depressed state and also had to contend with a two cents per pound U.S. tariff, an extremely high ad valorem rate, almost 100%. At the request of the Canadian fleet, the Dominion Government in Ottawa established a Halibut Marketing Board under the Natural Products Marketing Act of 1934 that was implemented in June of that year by an Order in Council. The legally supported program provided between-trip tie-ups of seven days in Areas 2 and 3, depending on vessel size, similar to the U.S. program. The Dominion Act was invalidated in 1936 in London, contested by the independent milk producers of British Columbia. Subsequently the halibut program was placed under the British Columbia Marketing Act.

Despite the fact the program had the force of law in Canada, infractions of the plan were no less than with the U.S. fleet under the voluntary plan. Numerous strategies were used in both countries for circumventing the program and in most case they were incapable of being detected. This eleven year episode in the history of the fishery was significant in the further development of the modern day industrial fishery. Distribution and timing of the landings were two of the most important aspects. Although it is impossible to prove that the economic condition of the fleet was improved, it cannot be denied that the program did reduce the great concentration of landings and also lengthened the fishing season. These actions promoted a more orderly flow to market of the allowable catch, and the longer season had a definite conservation value.

The Great Depression era in the fishery revealed some characteristics of the fleet that would otherwise have been overlooked. According to Bell, “very few, if any industries have been able to exercise such self control over its members for such a long time as did the Halibut Control Board from 1932 to 1942 inclusive. These were difficult years. The negotiation and implementation of such a complex voluntary program of individual restraints is a monument to the self-reliance of the fleet. It also reflected credit upon the leadership of over a dozen organizations involved and particularly Harold E. Lokken, manager of the FVOA in Seattle. This group represented the largest segment of the fleet. It initiated most of the programs and bore its full share of self restraint (Bell, p.142). In retrospect the halibut industry “curtailment” program of the 1930s became a voluntary limited entry program.

Although all initial goals may not have been met and despite complications for all concerned, this eleven year effort of self-help left the fleet still independent of government handouts such as price supports, subsidies and other misleading benefits so widely indulged in by agriculture. Since the program was basically voluntary, there was an increasing number of infractions. The Commission was unable to engage in policing the program due to the provisions of the conventions. The infractions were mostly violations of the poundage limitation per-man-per-trip. They reached serious levels as the years went on and both threatened the program and posed major threats to the integrity of the Commission’s statistical system. Both the fleet and the Commission made concerted and repeated efforts to have the Halibut Convention amended to permit assistance in implementing the program, those efforts failed.

After the end of World War II, programs were occasionally discussed to improve the economic state of the fishery but it was not until the mid-1950s that there was any concerted coastwide effort to reinstate any plan. By this time fishing seasons had become extremely short with a great concentration of landings and ex-vessel halibut prices at a relatively low level compared to prices of other commodities.

Sixty years later in 1995, following positive experiences with the voluntary Halibut Control Board from 1932 through 1942, namely with delayed vessel departures, individual vessel catch limits and the layups, the halibut fleet created an orderly flow of product to the market, a nine-month season, a safer fishery, and vastly improved prices with implementation of the Individual Fishing Quota program (IFQs) under the management of the North Pacific Fishery Management Council, the Department of Fisheries and Oceans and the International Pacific Halibut Commission. It is noteworthy that the Manager of the FVOA was present at the December 1991 NPFMC meeting where he made the motion to enact the halibut and sablefish IFQ program. Twelve years later in 2003, he made the motion to enact the sablefish IFQ program at a Pacific Fishery Management Council meeting.