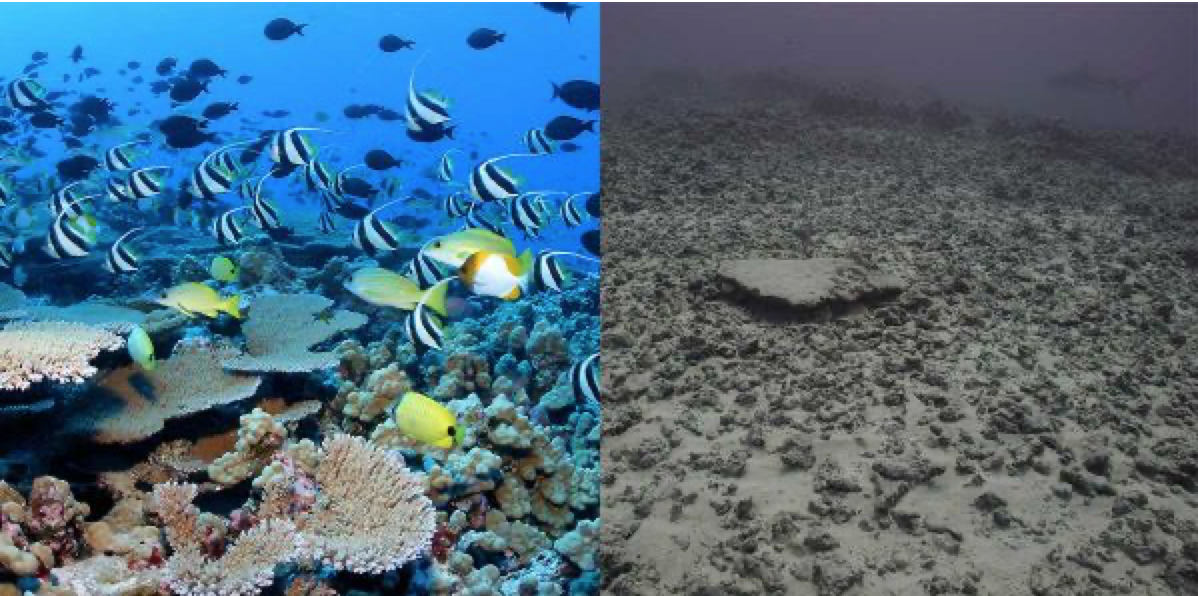

An international analysis of coral reefs found a global loss in reef area of 14 percent – about 4,517 square miles, more than all the living coral off Australia – as rising sea surface temperatures take their toll on that critical fish habitat.

The report “Status of Coral Reefs of the World: 2020,” released Oct. 5, is sixth edition produced by the Global Coral Reef Monitoring Network. The largest analysis of global coral reef health ever undertaken, the paper documents the 14 percent loss calculated between 2009 and 2018, drawing on data from 12,000 sites in 73 countries.

“Corals reefs across the world are under relentless stress from warming caused by climate change and other local pressures such as overfishing, unsustainable coastal development and declining water quality,” according to a statement by network scientists.

“An irrevocable loss of coral reefs would be catastrophic. Although reefs cover only 0.2 per cent of the ocean floor they are home to at least a quarter of all marine species, providing critical habitat and a fundamental source of protein, as well as life-saving medicines. It is estimated that hundreds of millions of people around the world depend on them for food, jobs and protection from storms and erosion.”

The report also found many coral reefs can recover if conditions improve – include nations taking steps to stabilize atmospheric emissions and reduce future ocean warming.

“This study is the most detailed analysis to date on the state of the world’s coral reefs, and the news is mixed. There are clearly unsettling trends toward coral loss, and we can expect these to continue as warming persists,” said Paul Hardy, CEO of the Australian Institute of Marine Science.

“Despite this, some reefs have shown a remarkable ability to bounce back, which offers hope for the future recovery of degraded reefs. A clear message from the study is that climate change is the biggest threat to the world’s reefs, and we must all do our part by urgently curbing global greenhouse gas emissions and mitigating local pressures,” said Hardy.

The analysis of 10 coral reef-bearing regions around the world showed that coral bleaching events caused by elevated sea surface temperatures (SSTs) were the main driver of coral loss, including an acute event in 1998 that is estimated to have killed 8 percent of the world’s corals. That alone was more than all the coral now living on reefs in the Caribbean or Red Sea and Gulf of Aden regions.

The longer-term decline seen during the last decade coincided with persistent elevated SSTs.

The analysis looked at changes in the cover of both live hard coral and algae. Live hard coral cover is seen as a scientific indicator of coral reef health, while increases in algae are a widely accepted signal of stress to reefs.

Since the oldest data used in the report, which dates to 1978, there was a 9 per cent decline in the amount of hard coral worldwide. Between 2010 and 2019, the amount of algae has increased by 20 per cent, corresponding with declines in hard coral cover, researchers found.

“This progressive transition from coral to algae-dominated reef communities reduces the complex habitat that is essential to support high levels of biodiversity,” they note.

The report also points out that intervals between mass coral bleaching events has been have not given coral reefs time to fully recover, although some recovery was observed in 2019 with coral reefs regaining 2% of the coral cover.

“This indicates that coral reefs are still resilient and if pressures on these critical ecosystems ease, then they have the capacity to recover, potentially within a decade, to the healthy, flourishing reefs that were prevalent pre-1998,” the report states.

Large scale coral bleaching events are the greatest disturbance to the world’s coral reefs. The 1998 event alone killed eight per cent of the world’s coral, which is the equivalent of about 2,509 square miles of coral.

The greatest impacts of this mass bleaching event were seen in the Indian Ocean, Japan, and the Caribbean, with smaller impacts observed in the Red Sea, The Gulf, the northern Pacific in Hawaii and the Caroline Islands, and the southern Pacific in Samoa and New Caledonia.

Among other findings in the report:

● Reef algae, which grows during periods of stress, has increased by 20 per cent over the past decade.

● Prior to this, on average there was twice as much coral on the world’s reefs as algae.

● Coral reefs in East Asia’s Coral Triangle, which is the centre of coral reef biodiversity and accounts for more than 30 per cent of the world’s reefs, have been less impacted by rising sea surface temperatures. Despite some declines in hard coral during the last decade, on average, these reefs have more coral today than in 1983 when the first data from this region were collected.

● Almost always, sharp declines in coral cover corresponded with rapid increases in sea surface temperatures, indicating their vulnerability to spikes, which is a phenomenon that is likely to happen more frequently as the planet continues to warm.