Teledyne Marine and Rutgers University are launching an autonomous underwater vehicle on a first-ever, five-year global mission to collect data for ocean scientists.

Teledyne’s Redwing, the most advanced commercial subsea glider ever developed, would become the first underwater robot to circumnavigate the globe, Teledyne and Rutgers experts say.

“We live on an ocean planet,” said Rutgers scientist Oscar Schofield, who with fellow oceanographer Scott Glenn has worked on applying undersea glider technology over two decades. “All weather and climate are regulated by the ocean. This mission will give us another tool we need to achieve real understanding.”

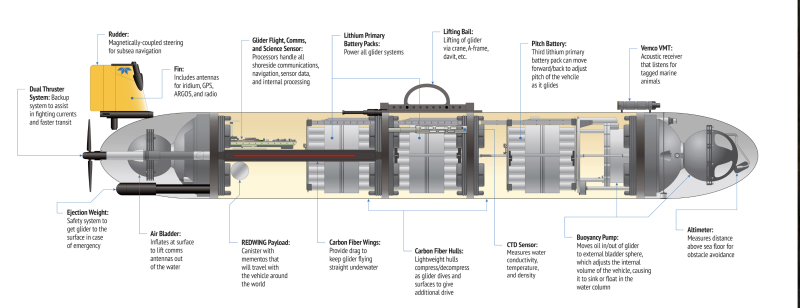

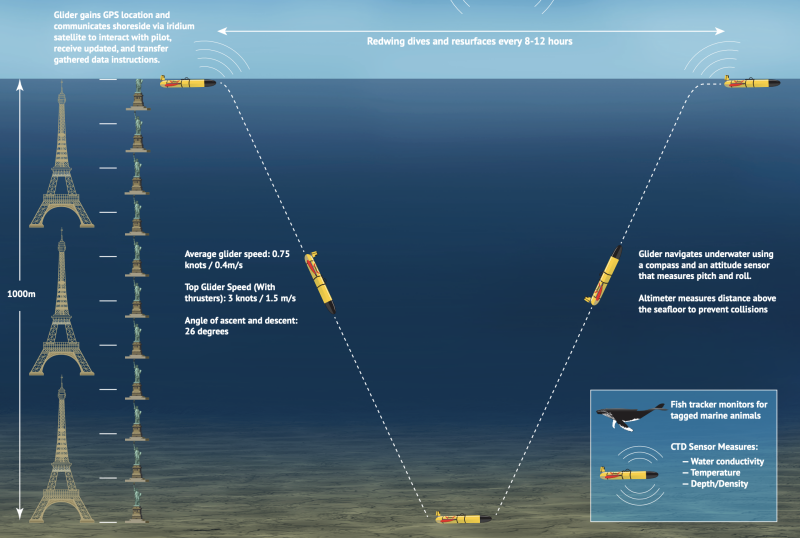

On their wings, autonomous gliders ‘fly’ under the sea surface, moving at very low speed with only a small thruster propeller, mostly using ballast water and tiny pumps to adjust their buoyancy and glide in zig-zag paths through the water column, while onboard sensors record data.

Early gliders, deployed by scientists from small boats off southern New England and the Mid-Atlantic coasts in the late 1990s, conducted short expeditions of days at a time, surfacing to transmit data by telemetry links.

In 2009 a Rutgers team launched a glider on a first trans-Atlantic crossing, traveling more than 7,300 miles in 221 days before landing at Baiona, Spain, where Christopher Columbus’s crew returned in 1493 from his expedition. The new Redwing expedition would emulate captain Ferdinand Magellan’s 1519-1522 circumnavigation – in a next-generation Slocum Sentinel Glider by Teledyne.

“We’ve scaled our product to give it more capability,” said Shea Quinn, Teledyne’s Glider Product Line manager and lead on the Sentinel Mission. “This glider has the endurance and energy to do more than any other vehicle could. It’s designed to stay out there for a year or two at a time.”

“We’re onto the third generation of gliders and there is still a fourth generation. That’s what this Sentinel is about,” said Glenn.

New designs are “significantly bigger,” with improved wings and more battery power, said Scholfield. “By being bigger, you can carry a lot of exotic sensors and be out there for months, compared to three or four days for a traditional glider.”

The Slocum Glider design was named for Joshua Slocum, an American seaman famed for making the first single-handed sailboat circumnavigation in 1895-98. The late Doug Webb, a longtime senior oceanographer at the Woods Hole Institute, developed and tested the first Slocum glider in the late 1990s in the ocean near Tuckerton, N.J. working with Rutgers oceanographers.

Webb was a Massachusets neighbor of Henry Stommel, “arguably the most important oceanographer of the 20th century, and they often discussed/debated the future of exploring the world’s ocean,” according to a Rutgers history of glider research.

“These discussions were the inspiration for a manuscript published in 1988 by Henry Stommel – ‘The Slocum Mission’. The manuscript envisioned long-duration underwater robots conducting research across the globe as they sailed under the control of graduate students remotely.”

“They had this whole concept of a world ocean observing system,” said Glenn.

The vehicle’s name Redwing is an acronym for “Research and Education Doug Webb Inter-National Glider,” recognizing Rutgers’ scarlet school colors and memorializing inventor Webb, who founded Webb Research, the predecessor organization that became Teledyne Marine. WHOI now operates the second largest glider fleet in the world, conducting climate research and supporting protection of endangered species such as the North Atlantic right whale.

It's planned for the glider to ride the Gulf Stream from south of Martha’s Vineyard toward Europe, swinging south to stop at the island of Gran Canaria northwest Africa, then on to Cape Town in South Africa. Rounding the Cape of Good Hope, the Redwing will cross the Indian Ocean to Australia, then on to New Zealand.

Then navigating the Antarctic Circumpolar Current near the Straits of Magellan will take the glider into the South Atlantic to reach the Falkland Islands. Mission planners say they may put the robot into port in Brazil and the Caribbean before returning to southern New England.

The plan is to progress from “glider port to glider port” with minimal use of big support vessels, said Glenn. If the glider gets into trouble on the high seas, “it has a lot of survival instincts” and can alert mission controllers to arrange a rescue, he said.

During early work with small gliders, “we’ve had a lot of interesting rescues over the years,” said Scott, recalling the vehicles’ encounters with divers and fishermen.

At 8.4’ long and 1’ diameter, the Sentinel gliders weigh in at 377 pounds deadweight, with 7.7 pounds of instrument payload and 23 kWh of electrical power. At gliding speed around 1 knot the vehicles are rated to dive too 1,000 meters, or 3,280’.

Onboard navigation is enabled with Global Positioning System, pressure sensors, altimeter, with communication to the mission control home base via radio frequency modem, Iridium (RUDICS) and ARGOS.

Swimming through the water column, Redwing records three-dimensional views of the ocean.

Real-time data is transmitted via satellite link every eight to twelve hours. The glider will check in with WHOI scientists every time it comes up to the surface, and if it can’t connect, the vehicles just keeps going on course.

The data flows to WHOI come through Bigelow Laboratory, where the upper story rooms are well known to oceanographers like Glenn who started careers there. “The attic of the Bigelow building, where the students work,” Glenn recalls.

The legacy of science education continues with the Redwing mission. More than 50 undergraduates are enrolled in a research class taught by Glenn and Schofield that tracks Redwing’s progress and post updates blogs about its discoveries.

Brian Maguire at Teledyne Marine says detailed ocean data obtained during the Redwing mission “will deliver early warnings of extreme weather and will track the impact of shifting ocean currents so that we can refine long-term climate projections in a way that scientists have dreamed of for decades.”

Gliders have already earned their place in storm tracking history. In 2011-2012 Rutgers graduate students launched gliders in the path of hurricanes Irene and Sandy as they steamed toward New Jersey. The robot documented dramatic mixing of ocean waters, adding to scientists’ understanding of how storm surges devastated coastal communities.

“That led to the hurricane glider fleet, those back-to-back hurricanes of Irene and Sandy,” said Glenn. “Now there are more than 100 glider missions” launched by scientists during hurricane seasons, he said.

Teledyne has produced more than 1,200 gliders. Years ago Rutgers scientists were excited to have three in their fleet, said Scholfield. The technology has enabled oceanographers to work “at sea” every day.

“We’re really proud of that,” said Glenn.