A building wave for offshore wind energy surged out of the Biden administration, with March 29 announcements that set a goal of building 30,000 megawatts of capacity and opening up to 800,000 more acres for leasing in the New York Bight.

Two weeks later, the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management moderated the plan, withdrawing potential leasing areas off New York — acknowledging conflicts with commercial fishing, maritime traffic and tourism that will be rife in the East Coast’s most crowded waters.

But on a broad scale, it appears to be full speed ahead for BOEM. Even during the Trump administration’s fitful approach to offshore wind, the agency itself worked consistently to make leasing possible for wind power developers.

News Break: Biden administration clears way for Vineyard Wind

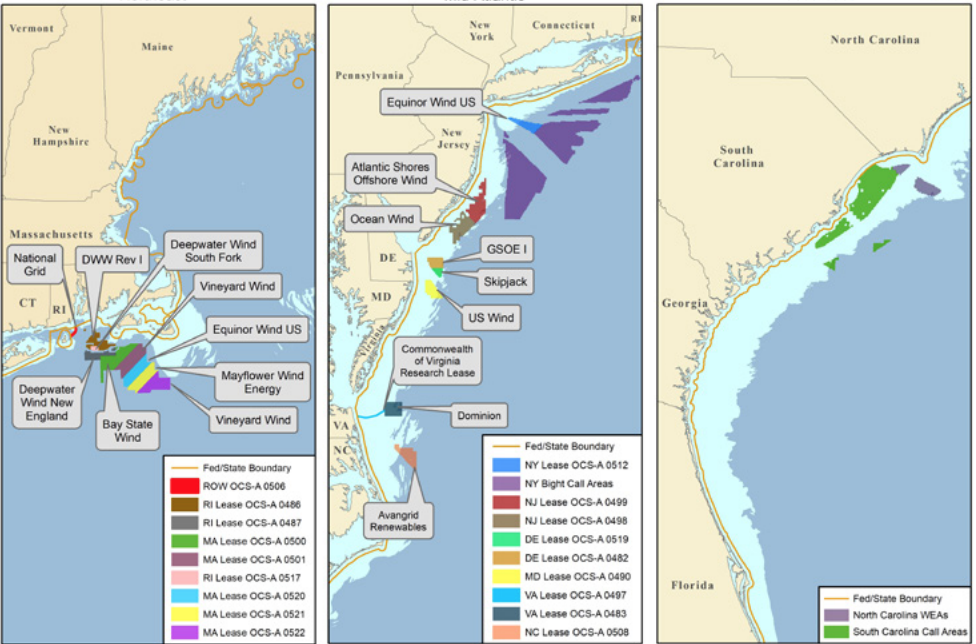

Today there are 17 active leases, comprising 1.7 million acres, says BOEM Director Amanda Lefton. Ten more environmental reviews could be started this year, and construction and operation plans for 16 projects could be in place by 2025, Lefton said during an April 14 online meeting of BOEM’s New York Bight task force.

Now an “all of government approach” is being brought to bear, and the “New York Bight will play a central role” in reaching the administration’s 30,000-MW goal, said Lefton. BOEM has “a steadfast commitment to do this right” by fishermen and other stakeholders, and the New York Bight is a place where collaboration is working, she said.

But one prominent group not in virtual attendance that day was the Responsible Offshore Development Alliance, a coalition of fishing groups and communities. The group has been meeting for years with BOEM planners and wind developers, but in recent weeks reacted with alarm to the Biden administration’s full-court press to expand the industry.

“Fishermen have shown up for years to ‘engage’ in processes where spatial constraints and, often, the actors themselves are opposed to their livelihood,” according to a letter RODA submitted to the task force, stating it would boycott the meetings in protest.

“This time and effort has resulted in effectively no accommodations to mitigate impacts from individual developers or the supposedly unbiased federal and state governments,” the letter says. “Individuals from the fishing community care deeply, but the deck is so stacked that they are exhausted and even traumatized by this relentless assault on their worth and expertise.”

The Interior Department formally reversed a Trump-era legal opinion on offshore wind energy, with an April 9 memo by Robert Anderson, the department’s principle deputy solicitor. That opinion critiqued and reversed findings written in December by Daniel Jorjani, who was the department’s top lawyer when then-Interior Secretary David Bernhardt moved to shut down the approval process for the Vineyard Wind offshore project.

In that earlier 16-page document, Jorjani held that if Bernhardt “determines that either fishing or vessel transit constitute ‘reasonable uses… of the exclusive economic zone, the high seas and the territorial sea,’ the Secretary has a duty to prevent interference with that use.”

Moreover, Jorjani wrote, the Interior secretary should determine “what is unreasonable” interference from offshore wind turbines “based on the perspective of the fishing user.” That was a victory for commercial fishing advocates who had gone directly to Bernhardt with their concerns.

In the new memo — five pages dense with analysis of the Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act and related court decisions — Anderson wrote that the act requires the Interior secretary to consider a dozen specific goals of the law when making decisions.

Those factors could favor “actions to maximize low-emission and renewable electrical generation from offshore wind facilities,” Anderson wrote.

The bureaucratic memo further paved the way for a BOEM record of decision to approve the 800-megawatt Vineyard Wind project off southern New England, where RODA and other fishing industry advocates have pushed the developers and BOEM to include mitigation measures.

Fishermen sought 4-nautical-mile-wide transit lanes to ensure safe passage through wind energy areas in heavy weather. Developers and Coast Guard officials said 1-nm spacing between turbine towers on lease areas will be adequate. The final record of decision would include a ruling on that.

“Technically, we don’t know,” said Annie Hawkins, executive director of the Responsible Offshore Development Alliance, while awaiting that decision. “They could address some of these fisheries issues (in the decision). It doesn’t look promising.”

Commercial fishing groups that at best have had a rocky relationship with BOEM and wind developers were shaken by the breadth of the administration’s goals. Hawkins said there was no sign of new commitment to head off potential conflicts between the industries.

“These fisheries questions have been around for a decade,” said Hawkins. “We don’t have an interagency process” for understanding and resolving them, she added: “We’re just blown away by the lack of coordination.”

Ringing White House endorsements of wind power call into question how federal agencies will handle reviews under the National Environmental Policy Act and other regulatory measures, said Hawkins.

“Can you imagine if this assessment was for oil and gas (development)? How would that look?” she said. “This whole thing is so upside-down. It’s not like the way we regulate any other resource.”

While RODA sat out the New York Bight meetings, NMFS was represented. The agency did not hold back on its view of potential environmental and fisheries impact should more wind energy areas be developed in the New York Bight.

The region “is one of the most important areas on the East Coast for commercial and recreational fisheries,” said Sue Tuxbury, a fisheries biologist in the agency’s habitat conservation division who works on wind energy and hydropower activities.

Surf clams and scallops, two of the most valuable East Coast fisheries, have major shellfish resources on the bottom. “The location and number of turbines” will be a major factor in whether those dredge fisheries can continue to operate around the wind areas, said Tuxbury.

She recommended that BOEM and the bight task force consult RODA’s 2019 workshop on fishing vessel transit issues — and for the agency to hold new meetings with commercial fishermen to to discuss potential traffic lanes for New Jersey ports Barnegat Light and Cape May, close to the planned Ocean Wind and Atlantic Shores turbine arrays.

Tuxbury said unknown environmental questions include how those arrays may affect the Mid-Atlantic cold pool, the seasonal stratification of water temperatures that is influential on the life cycles of fish and other marine life. New surveys and scientific modeling are needed to anticipate how those changes may happen and play out, she said.

BOEM’s proposed wind energy areas include essential fish habitat “for nearly every species” managed by NMFS and the New England and Mid-Atlantic fishery management councils, said Tuxbury. Building turbines out there “will directly impact” the agency’s ability to conduct at-sea scientific surveys that managers depend on to make decisions, she said.

Survey vessels operated by NOAA will likely be excluded from operating their trawl sampling gear in wind energy areas by spatial constraints between turbine towers. Along with the need for longer vessel transit times to get around arrays, that will reduce biological sampling, said Tuxbury.

Fishing conflicts were one reason BOEM planners cited in dropping two areas near Long Island from immediate consideration for offshore wind energy leases.

The Fairways North and South areas, named for nearby shipping approaches to New York Harbor, have scallop and surf clam beds, issues with maritime traffic and whale feeding areas, and the potential for raising the ire of beachfront homeowners and tourism businesses on Long Island’s South Shore.

New York state officials recommended against planning for leases in the Fairway areas, saying the closest 15-mile proximity to Long Island runs counter to the state’s policy of keeping wind generation at least 18 miles from shore.

With offshore wind development gaining momentum, resistance could build on other residential shorelines. That was evident as BOEM initiated its environmental review process for the Ocean Wind project, Ørsted’s planned 1,100-MW array off Atlantic City.

“We’re very concerned about the impact on tourism,” said Beach Haven, N.J., Mayor Colleen Lambert during BOEM’s April 15 online scoping meeting on Ocean Wind. The Ocean Wind tract at its closest is 15 miles offshore, and turbine blades could be visible from shore on some days, according to BOEM visual simulations.

BOEM has been gauging potential developer interest in areas farther offshore, and the task force is part of its environmental assessment of those areas. Those developments could be lowed by a shortage of wind turbine installation vessels with more projects planned in Europe and Asia.

In U.S. waters, developers will need to abide by the Jones Act — the 1920 federal maritime law that requires using U.S.-flagged vessels and crews.

Vineyard Wind’s plan is to use Belgium-based DEME Offshore’s installation vessels, teamed with U.S.-flag vessels of Foss Maritime, using the “feeder” concept of a foreign-flag wind turbine installation vessel supplied onsite by Jones Act-compliant U.S. vessels.

Virginia-based Dominion Energy is backing construction of its own 472-foot U.S.-flagged installation vessel, amid widespread concern in the industry that global demand for services of those heavy-lift vessels could slow the development of projects in U.S. waters.

All that action now is focused on the shallow outer continental shelf from Cape Cod to the Carolinas. But wind developers are already looking ahead to float anchored wind turbines in deep water like the Gulf of Maine.

“We’re trying to keep Maine waters free from this industrialization,” said Dustin Delano, a Friendship, Maine, lobsterman who helped organize a March 21 demonstration by fishermen with more than 80 boats on the water protesting plans for offshore wind.

“This would fill the ocean with anchors, cables and chains,” said Delano. “Maine is unique in the nation. Our entire heritage is fishing and tourism.”

The Maine Aqua Ventus project would be a 12-MW floating turbine to test the feasibility of commercial-scale wind power arrays in the deepwater Gulf of Maine.

With the Biden administration promising $3 billion in loan guarantees to jump-start offshore turbine construction, a new Sea Grant program to study impacts on fishing seems a pittance to the fishing industry.

“That $1 million program for Sea Grant to find impacts of development on fishing communities “won’t understand the impact in one Maine lobster village,” said Hawkins.