Concerns raised by the maritime and commercial fishing industries now have federal officials considering wider buffer areas, and spacing as far as two nautical miles between proposed offshore wind power turbines.

At meetings in New York, Massachusetts and New Jersey, representatives of the federal Bureau of Ocean Energy Management said the burden of proof is on offshore wind energy development companies to show their plans for turbine arrays will be compatible with other ocean industries.

“Right now we’re asking developers to prove that fishermen can still fish” if offshore turbines are built, said Amy Stillings, an economist with BOEM.

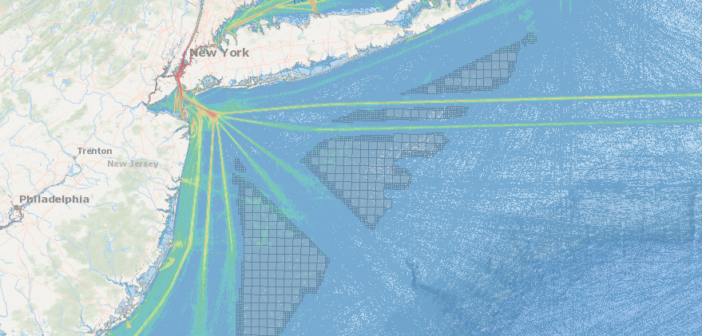

The agency is also looking at setting aside a corridor for shipping and barge traffic cutting across the New York Bight, which extends from Cape May Inlet, N.J., to Montauk Point, N.Y., on the eastern tip of Long Island, to maintain a safe buffer between future turbine arrays and vessel traffic.

That idea for a cross-Bight corridor nine nautical miles wide — a five-mile traffic lane, with two-mile buffers on either side — recognizes trends in maritime transportation that allow towing vessels to take the route farther offshore than the traditional paths closer to shore.

BOEM staffers met with fishermen and others in Riverhead, N.Y., New Bedford, Mass., and Long Branch, N.J., to discuss what the agency has heard from the public so far about the possibility of opening more of the New York Bight for federal wind energy leases.

Meanwhile, states in the region are aggressively soliciting proposals to get future power from offshore. The latest is New Jersey, where state utility regulators on Sept. 17 opened a window for companies to bid on selling 1,100 megawatts of offshore wind power into its local market. Gov. Phil Murphy wants to step it up with two more solicitations for 1,200 MW each in 2020 and 2022.

Combined with requests for proposals in New York and Massachusetts, New Jersey’s opening means the U.S. offshore market will be on the road toward 4 gigawatts by the end of 2019, and could reach more than 8 GW in the late 2020s, said Liz Burdock, president and CEO of the Business Network for Offshore Wind.

Not only do we have a growing pipeline, we have a growing commitment of scale,” Burdock said Friday at the Virginia Offshore Wind Executive Summit in Norfolk, Va. “There is a rush to scale along the East Coast.”

The “call area” outlined by BOEM includes potential locations for such future projects, in large offshore areas out toward the edge of the continental shelf between New Jersey and Long Island. Realistically, BOEM would lease much smaller sections of those areas, said Jim Bennett, head of BOEM’s renewable energy program.

The fishing boat Virginia Marise from Point Judith, R.I., near the Block Island Wind Farm. Deepwater Wind photo.

The agency is looking for ways to avoid or mitigate conflicts between a new offshore wind energy industry and established users in some of the most heavily trafficked and fished U.S. waters.

“Because there’s so much fishing in the New York Bight, there are really no areas that are not conflicted,” said Stillings. Conceptual maps drawn by BOEM staff – based on comments from the fishing industry – show how relatively small areas of minimal conflict would be far east toward the edge of the continental shelf.

Scallop fishermen have already gone to federal court over wind energy development, saying rows of turbine towers could effectively shut them out of fishing prime mid-Atlantic grounds, making it too difficult and dangerous to pull dredges around 600′ towers and cables buried in the seabed.

“Back in the 1990s the government almost put us out of business,” said Art Ochse, captain of the scalloper F/V Christian & Alexa based in Point Pleasant Beach, N.J.

Faced with declining quotas then, scallop fishermen organized, got legal help and entered partnerships with scientists and regulators to rebuild the shellfish stock. Twenty years later, it is the richest U.S. fishery, but the prospect of being forced out of wind energy areas “is a knife right in the heart of our business,” said Ochse.

“We have said from day one that a minimum distance (between turbines) …has to be at least two nautical miles,” said Peter Himchak, who represented LaMonica Seafoods, a Cape May, N.J., surf clam processor, at the Sept. 20 meeting in New Jersey.

“And the columns (turbine towers) have to be straight, we can’t have these crazy patterns,” said Himchak.

Himchak was referring to staggered tower placements, as laid out in European offshore wind installations, to minimize turbines interfering with airflow around their neighboring machines. That has been a big issue for fishermen in southern New England, who want consistent planning among developers who have already obtained adjoining offshore leases from BOEM.

Those captains from New Bedford insisted wind developers must provide adequate fairways to ensure safe passage for boats crossing the continental shelf, said Stillings. BOEM has heard the call for a two-nautical mile clearance between turbines and is considering that in its analysis, she said.

In the New York Bight southwest winds prevail much of the year, a critical design consideration for wind developers, said Arianne Baker, a meteorologist with BOEM. That means arrays would not be arranged with direct north-south or east-west orientations, she said.

One rule of thumb is turbines need to be set apart a distance at least 10 times their rotor diameter, said Baker. For the 12-MW machines now envisioned by East Coast developers, that would be roughly 200 meters or 656′ — requiring a minimum distance around 1.25 miles.

Generally it is anticipated an 800-MW wind installation would require about 80,000 acres of seabed to construct, said Baker. The prospect of pushing towers even farther apart will widen their environmental impact, said Jim Lovgren, a captain with the Fishermen’s Dock Cooperative in Point Pleasant Beach.

If the government is to proceed with permitting turbines, it may be better to build them closer together in limited areas, and compensate fishermen for the loss of those grounds, he said.

“Four out of five European countries won’t let you fish in wind farms,” said Lovgren, whose co-op colleagues are mostly mobile gear fishermen who tow trawl nets and scallop dredges.

To fishermen, its looks like the federal government is pressing ahead on wind energy development without adequate environmental study of the potential effects of construction, turbine noise and electromagnetic fields around cables on sea life, said Lovgren.

“In my industry, we have to work on the precautionary principle,” he added. “You have science to prove it, or disprove it.”