For decades, Atlantic menhaden have been at the center of persistent and often heated debate in the Chesapeake Bay: is the industrial menhaden fishery operating sustainably, or is it putting the ecosystem at risk?

The challenge, according to a recent report from Virginia Public Radio, is that the data needed to answer that question definitively has never been fully settled, and fishing has continued in the meantime.

Menhaden are rarely eaten directly by humans, but they play a foundational role in the marine food web. As reported, Scott Harper once said, “humans do not eat menhaden, but just about everything else in the marine environment does,” a quote Virginia Public noted remains central to the debate more than 20 years later.

The uncertainty has prompted efforts to better understand menhaden abundance in Chesapeake Bay. A federal bill headed to the president’s desk would allocate $2.5 million for a study conducted by NOAA. Additional proposals include a Virginia Assembly Bill requesting a study, a petition before the Virginia Marine Resources Commission (VMRC), and an industry-funded research effort.

Not everyone believes more studies will lead to meaningful action. “What I see here, which is a little cynical, is an effort to continue to study,” shared David Reed, executive director of the Chesapeake Legal Alliance, in an interview with Virginia Public. “It’s just, ‘well, can I have another three million dollars to do a different study?’… and it just feels like a road to nowhere.”

Reed, a former biologist turned attorney, said he is concerned that scientific processes are being used to delay decisions rather than resolve long-standing questions. While the Chesapeake Legal Alliance was not involved in the most recent VMRC petition, it has previously backed efforts to restrict industrial menhaden fishing, which supplies Omega Protein with hundreds of thousands of tons of menhaden each year.

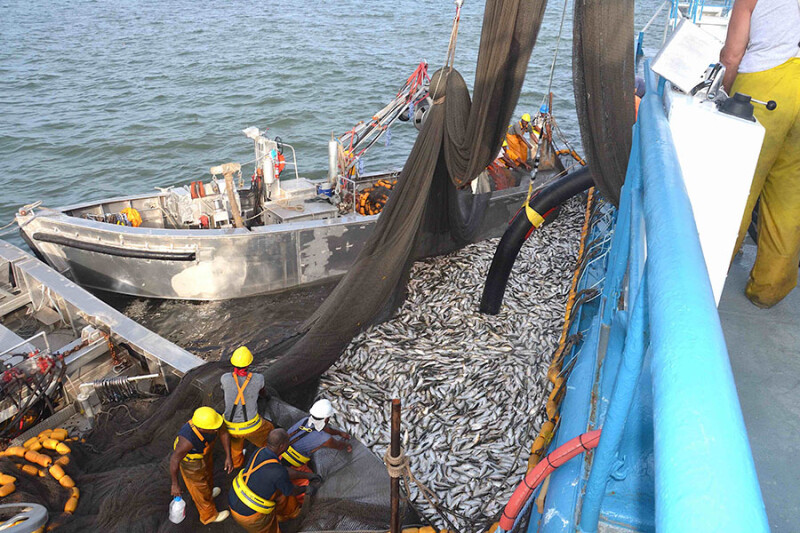

Omega Protein operates one reduction plant supplied by six fishing vessels and six spotter planes. The company maintains that its fishery is sustainable and supported by existing science. However, historical records cited in the report paint a more complicated picture. A 1975 NOAA report referenced by Virginia Public documented the disappearance of older menhaden between 1954 and 1968, attributing those changes to increased fishing efficiency, a growing fleet, and longer fishing seasons.

Beyond Chesapeake Bay, menhaden’s importance is often poorly understood by the public, according to a separate article by Ryan Lockwood of the Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership. Lockwood wrote that many people are unfamiliar with menhaden until they hear them referred to by common regional names like bunker or pogy.

Once people understand what menhaden are, Lockwood shared, their role as a keystone species quickly becomes clear, particularly as forage for striped bass, tuna, redfish, and other marine life. During a Mid-Atlantic road trip, Lockwood spoke with charter captains, conservation leaders, and coastal residents who connected menhaden abundance to everything from sportfishing to whale sightings.

As new studies are proposed and debated, the question facing managers, fishermen, and policymakers remains whether additional research will finally provide clarity or simply prolong a discussion that has already spanned decades.