Some $305 million in mitigation costs for a planned Mississippi River sediment diversion project could include money for re-establishing south Louisiana oyster seed beds and new shellfish cage culture, and grant money for new gear and onboard refrigeration for shrimp fishermen who will need to sail farther for their catches.

But plans for the Mid-Barataria Sediment Diversion acknowledge there may be the need to pay for “workforce training to improve business practices or to facilitate transitions to a new type of employment.”

Fishermen in the Barataria Basin region are in line to suffer collateral damage in the struggle to save Louisiana’s coastal marshes, collapsing from decades of erosion wrought by oil and gas development, channel dredging, hurricanes, sea level rise and the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill.

Virtual public meetings online start on Monday, March 22, part of a 60-day public comment period on the Corps of Engineers environmental impact statement for the diversion project. Background documents and registration links to sign up for the sessions are available here online.

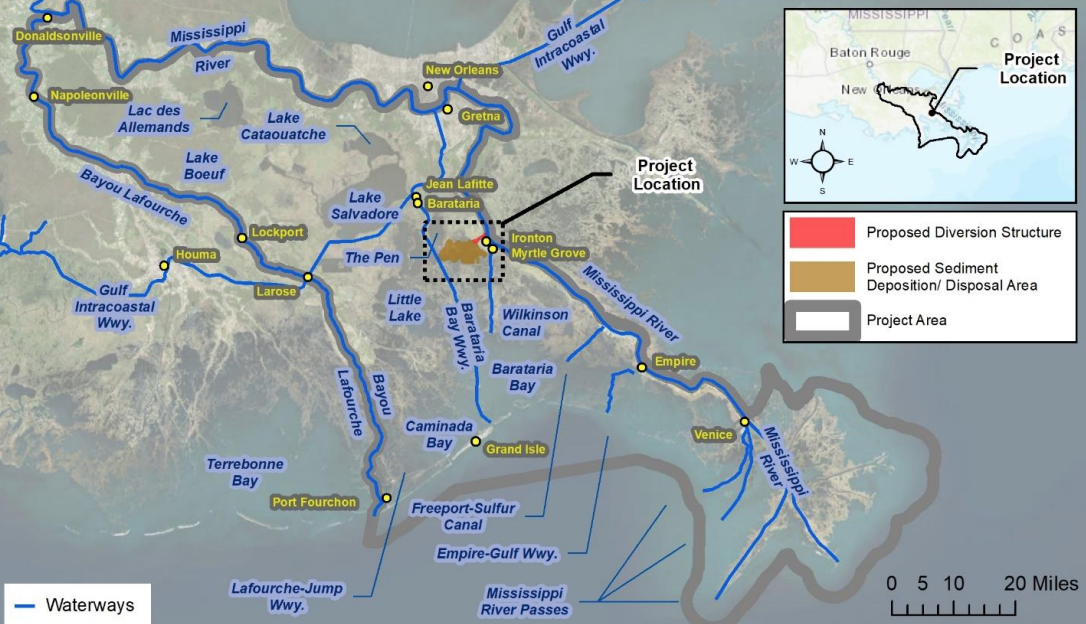

The Corps of Engineers statement issued March 5 found that a future with a two-mile long, concrete-lined channel funneling up to 75,000 cubic feet per second of sediment-laden fresh water from the river would be the best prospect for rebuilding the vanishing Barataria wetlands.

The region’s brown shrimp fishery and oyster culture will suffer major impact from all that fresh water diluting salinity – as will the bottlenose dolphin population of Barataria Bay, the Corps concluded.

A March report from The Louisiana Trustee Implementation Group, drawn from state and federal agencies entrusted with allocating the Deepwater Horizon settlement money, says it is a price that must be paid.

“Ultimately, the Trustees’ analysis has determined that, as with many environmental restoration projects, there would be ecological tradeoffs associated with any of the large-scale sediment diversion alternatives,” the group wrote in a draft restoration plan released this month.

“The benefits would be significant and would primarily derive from the creation of thousands of acres of marsh that, with a steady supply of Mississippi River sediment, would be sustained over decades even in the face of rising sea levels and coastal erosion.

“The Trustees also recognize that any of the large-scale sediment diversion alternatives considered would also result in collateral injuries to some natural resources,” the report says.

The Barataria Basin estuary has been eroding and degrading for more than a century, a trend that started when levees cut off sediment input from the Mississippi, and the concept of using a diversion project has been debated since the Corps of Engineers issued a feasibility report in 1984. State task forces made similar proposals through the 1990s and early 2000s.

Then the Deepwater Horizon explosion and fire happened April 20. 2010, triggering an 87-day oil spill of an estimated 134 million gallons into the northern Gulf of Mexico. In the damage assessments and restoration studies that followed, the Barataria Basin came into focus for its marsh and estuarine habitats used by the fish and wildlife species injured in the spill.

Restoration planners chose the Mid-Barataria location as the best for collecting and dispersing sediments and nutrients from the river. Mitigation costs are being estimated for the project downsides – including economic impact and increased flooding around small towns in the basin, potential loss of homes and fishing camps, and displacing fishermen.

Shrimp fishermen and oyster growers don’t believe proposed mitigation measures can come close to easing the damage that will be done, said George Ricks, resident of the Save Louisiana Coalition, an alliance of fishermen and communities who advocate using dredging and pipelines to move sediment rather than diversion.

“In the mitigation plan they talk about getting us money for freezers and such,” said Ricks. But the Barataria region produced nearly one-third of the state’s brown shrimp landings in 2019, and the notion that fishermen can make up for that by steaming farther is not realistic, he said.

The project’s likely impact on Barataria Bay’s bottlenose dolphins also rankles fishermen who helped with rescues during the Deepwater Horizon crisis, said Ricks. There are an estimated 2,000 dolphins in the population, and a Corps of Engineers environmental impact statement estimates the diversion could injure, kill or drive away nearly one-third of the mammals, he said.

“That’s nearly 600” of the federally protected species, said Ricks.

During the oil spill 91 dead dolphins were reported, said Ricks. In contrast during the 2019 Mississippi high water, when the Corps of Engineers opened the Bonnet Carré Spillway for 123 days, fishermen reported seeing 153 dead dolphins, he added.

“The river water killed more dolphins than the oil spill,” said Ricks.

In their draft plan, the trustees group calls for a statewide stranding program for 20 years that would provide rapid responses when live dolphins are found stranded to reduce stress on the animals treat them on site and if needed transport them to authorized rehabilitation facilities for additional treatment and care.

The stranding program would “improve diagnoses of the causes of illness and death in cetaceans to better understand natural and anthropogenic threats,” to help further restoration planning, the trustees group says.

Responding to oyster displacement should include re-establishing public seed grounds in the basin to help offset losses ; provide additional cultch material to current lessees to help maintain oyster reefs; and create broodstock reefs in the basin.

Alternative oyster culture, such as growing shellfish off the bottom in cages, could be another path, the trustees say, also offering funding to improve marketing and boost dockside harvest values.

“For the brown shrimp fishery, these restoration actions include supporting improvements in fishing gear and vessel refrigeration installation,” according to the trustees group plan. “For brown shrimp and finfish fisheries, the (trustees group) would support marketing to improve the dockside value of landings, as well as workforce training to improve business practices or to facilitate transitions to a new type of employment.”