The U.S.’s first ocean alkalinity enhancement (OAE) field trial in federal waters took place on Aug. 13, with the dispersal of 16,500 gallons of sodium hydroxide into the Gulf of Maine. Led by a team of Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute (WHOI) scientists, this milestone represents the culmination of three years of planning, which for the last year has included a steady stream of feedback (including some unvarnished pushback) from the fishing industry.

I joined the field trial as a fishing industry observer, and this is my report to the fleet.

Fishing industry involvement in project planning

Ocean alkalinity enhancement was an enigmatic term to the New England fishermen who heard it for the first time in summer 2024, when the EPA opened a public comment period for input on a permit WHOI’s LOC-NESS (Locking Away Carbon in the Northeast Shelf and Slope) project.

“We don’t have a lot of tolerance for your curiosity right now,” and “The ocean's not a lab rat,” were some of the comments made by anxious fishermen during the first informational meetings hosted by the WHOI team.

In the year since that first exposure, fishermen and their representatives have attended numerous meetings with the LOC-NESS team at port meetings, trade shows, and New England Fisheries Management Council meetings. As a result of fishermen’s input, the scientists changed the planned location of the project and lined up federal funding (later retracted) to test the effects of sodium hydroxide on the larval and egg stages of commercially important species like lobster and herring.

When the time came to perform the field trial, it seemed appropriate to ask if a fisherman could witness the event as an observer, so I asked if I could tag along. They were happy to oblige, and even set aside a tie-up stipend so I wouldn’t lose income due to time away from my fishing job.

Bearing witness to the field trial

I greeted the morning of Aug. 13 in the Wilkinson’s Basin with 15 other people aboard the offshore support vessel Peter M. Mahoney. The vessel was under contract with the LOC-NESS team to disperse 16,500 gallons of highly alkaline sodium hydroxide into surface ocean waters. Nearby was the research vessel Connecticut, carrying a team of LOC-NESS scientists and their data collection instruments.

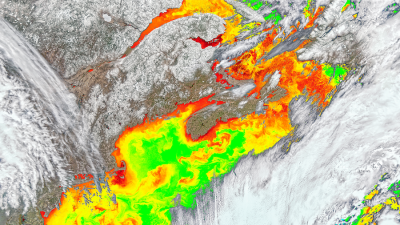

At 9 a.m., the Connecticut cued the Peter M. Mahoney to start the release. Within seconds, a shot of hot pink liquid emerged from a nozzle at the Mahoney’s stern; this was the color of the rhodamine tracer dye that the team was mixing with the sodium hydroxide to make the alkalinity-enhanced patch of seawater visible.

Over the next six hours, the Peter M. Mahoney moved in circles while slowly draining four ISO container tanks of sodium hydroxide. As the hours passed, the patch of alkalinity-enhanced seawater grew to 800 meters in diameter and became an intense crimson color. All the while, the Connecticut trailed the Mahoney by 200 meters, measuring alkalinity, fluorescence (an indicator of dye concentration), and various other parameters.

The LOC-NESS project’s EPA permit imposed various environmental and safety requirements related to chemical flow rates, trip duration, and marine mammal sitings. The only correction that the team had to make during the dispersal was to adjust the sodium hydroxide flow rate downward by 50% about three hours into the event because the R/V Connecticut’s readings of seawater pH had surpassed the EPA’s allowable threshold of 8.7 by a hair.

I undertook this adventure to ensure that the fishing industry has access to trusted information about the unprecedented LOC-NESS experiment. I also did it to make a broader point. Fishermen are required take scientific observers on our vessels to monitor our catch and bycatch. With marine carbon dioxide removal (mCDR) likely to become a more common focus of ocean research (and commercial activity) in the future, the fishing industry must have unfettered access to information about project plans and findings. Securing a spot for a fishing industry observer on every mCDR field trial is one simple step we as an industry can take to support transparency and to build our own literacy in these novel methods as they unfold.

A complete write-up of my field notes can be found in “A fisherman bears witness to WHOI’s alkalinity experiment in the Gulf of Maine.”

Scientific takeaways

A week after the dispersal was complete, I caught up with two of the scientists leading the project: Adam Subhas and Jennie Rheuban. Stationed on the Connecticut, they remained with the alkaline patch for four days after the dispersal, relying on the patch’s red color and a set of drifter buoys to track the patch’s location as it shifted with the currents.

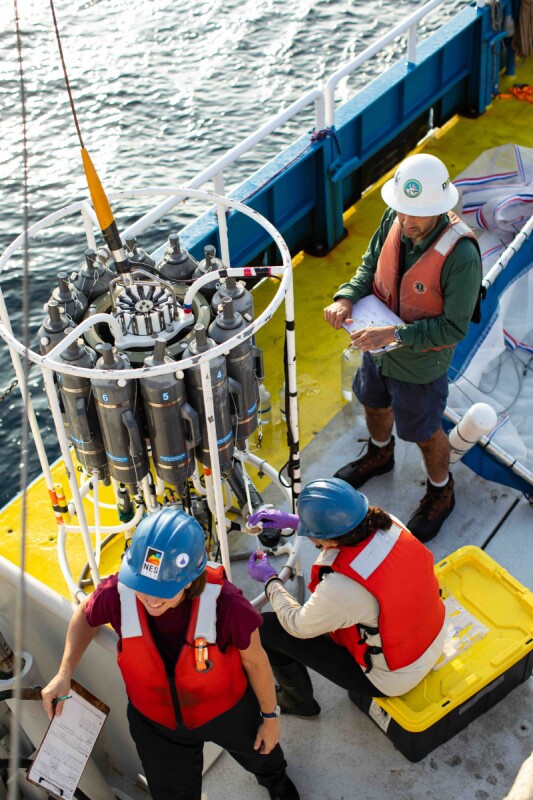

During those four days, they deployed CTD rosette casts (short for Conductivity, Temperature, and Depth), Bongo plankton nets, and neuston nets to obtain measurements about how the patch of water responded to the sodium hydroxide addition physically, chemically, and biologically. A set of autonomous gliders and an autonomous underwater vehicle continued to patrol the patch for an additional week after the Connecticut returned to port, transmitting data on temperature, salinity, oxygen, pH and turbidity, rhodamine fluorescence (concentration of the dye), and movement of ocean currents.

Although it will take at least half a year for the science team to fully digest the data they collected during the field trial, Rheuban and Subhas were ready to share a few early takeaways.

“We clearly saw a decrease in the CO2 concentration of seawater,” Subhas said. “We can conclusively say already that we have successfully enhanced the alkalinity of seawater, and we set up the conditions for carbon uptake into the patch. The challenge for us moving forward is to then synthesize all these datasets and actually quantify how much carbon actually got removed from the atmosphere due to the experiment.”

As for impacts to sea life, Subhas concluded, “We didn't observe any protected species. There were no indications of mass mortality events… When we were looking at the photosynthetic health metric, there weren't any major things that popped out… There hasn't been anything that we've looked at so far that has said there was a major impact to the biological community.”

My full interview with Jennie Rheuban and Adam Subhas can be found at “Post-field trial debrief with the LOC-NESS science team.” A WHOI press release can be found at here. All of the data collected by the team will be made publicly available after it is processed.

The broader outlook for ocean alkalinity enhancement

While the LOC-NESS project is focused on meticulously answering scientific questions about the measurability and ecological impacts of OAE as an mCDR strategy, commercial interests in the mCDR space are already marketing their projects to carbon offset buyers.

On Aug. 26, Frontier Climate, a joint effort backed by Stripe, Google, Shopify, Meta, and McKinsey, signed a $31.3 million dollar agreement with the Canadian climate tech startup Planetary for the delivery of OAE-based carbon credits. This announcement should jolt fishermen and their representatives into learning more about OAE and other forms of mCDR and taking steps to ensure that our industry is securing a voice for itself wherever it can. As we do that, research scientists like WHOI’s LOC-NESS team may prove to be valuable allies.

.png.author-image.300x300.png)