The biggest red salmon run in the world is building at Bristol Bay.

Up to 50 million fish could surge into its eight river systems in coming weeks, on par with past seasons. When it’s all done, the fishery will provide nearly half the global supply of wild sockeye salmon.

But this summer is different.

Beyond the restrictions and fears and economic chaos caused by covid-19, fishermen are waiting to learn if the development of a massive gold and copper mine that’s been hanging over their heads for two decades will get a greenlight from the federal government. The news is expected to come at the height of the summer season.

In mid-July, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers is expected to unveil its federal record of decision on the permit application by Northern Dynasty of Vancouver, Canada, to build the Pebble Mine at the sprawling mosaic of headwaters that provide the spawning and rearing grounds for the region’s salmon.

Three decisions are possible for the mine: issue a permit, issue a permit with conditions, or deny the application.

“As Bristol Bay’s fishermen head out to the fishing grounds for the next six weeks, we are counting on Congress to protect the 14,500 workers directly employed by the commercial salmon fishery,” said Andy Wink, executive director of the Bristol Bay Regional Seafood Development Association. “Pebble Mine is a threat to Alaskan jobs, America’s food security, and a salmon resource unparalleled anywhere on the planet.”

“The EPA’s own science shows that this project poses an unacceptable risk to our country's greatest remaining wild salmon runs,” said Katherine Carscallen, director of Commercial Fishermen for Bristol Bay. “We look to Alaska’s senators for their leadership and implore the EPA to use its authority under the Clean Water Act to veto Pebble’s permit.”

Such calls for help will likely go unheard.

Alaska’s two Republican senators and lone represenatative have staunchly stood behind the Pebble project’s right to go through a rigorous and fair permitting process and have been tightlipped about their opinions in the meantime.

Now that the process is pretty much a wrap, will they finally tell Alaskans if they are for or agin it?

“Congressman Young remains committed to seeing the process fully completed, but without a finished report, there is nothing that can be commented on,” said Rep. Don Young's Press Secretary Zack Brown.

“The federal permitting process is ongoing, and until there is a decision document to review, there is nothing on which to provide comment,” said Mike Anderson, communications director for Sen. Dan Sullivan.

Dr. Al Gross, Democratic candidate for U.S. Senate running against Sen. Dan Sullivan, said: "I know the developers have scaled back the scope of the mine to try to reduce the impact, but that doesn't change the fact that it's still at the headwaters of one of the world's most important salmon runs. And I'm worried that if they start small, that at some point in the near future they'll push to expand it. Nothing is going to change the fact that this is the wrong mine, wrong place, and even a small risk to this state and national treasure is too much.”

Alyse Galvin, Democratic candidate for U.S. House running against Rep. Don Young, said: “Alaska is a natural resource state and mining is a key part of our economy, however, so are our fisheries. I am opposed to the Pebble Mine Project because it is the wrong mine in the wrong location and represents too big a risk to Bristol Bay, the greatest salmon fishery in the world. We need Alaska’s representatives in Washington to once again be full-throated champions of Alaska’s fisheries.”

Sen. Lisa Murkowski’s office did not respond, but in the past, she has expressed some concern.

Surveys and polls show that a huge majority of Alaskans from all regions oppose the Pebble Mine. But equivocating with constituents is the way of today’s politicians.

The late Sen. Ted Stevens (R-AK) in 2008 stated emphatically and often: “I’m not opposed to mining, but Pebble is the wrong mine in the wrong place.” Love him or not, you always knew Uncle Ted’s stance on anything you asked him in his 40 year tenure in the U.S. Senate.

Alaska’s current reps in Congress might not dare to be open about Pebble, but investors are wiping their hands of the project.

Global investment banking firm Morgan Stanley, once the fourth largest institutional shareholder in Northern Dynasty, on March 31 dumped 99.14 percent in its shareholdings in the project, reported the National Resources Defense Council and CNN Money.

“While the reasons for Morgan Stanley’s recent sell-off are unknown, the global investment company is known as a strong proponent of the principle that environmental and social responsibility are essential to long-term investment success,” the NRDC said.

That sell-off is just the latest of Pebble put-downs on a global scale.

In 2011, Mitsubishi Corporation sold out. In 2013, Anglo American abandoned its partnership, walking away from a nearly $600 million investment. In 2014, Rio Tinto donated its shares to two Alaskan non-profits: Alaska Community Foundation and the Bristol Bay Native Corporation Education Foundation. In 2018, First Quantum Minerals walked away after five months from a $37.5 million investment and option for a 50 percent partnership. Also in 2018, BlackRock zeroed out its shareholdings.

New York investment firm Kerrisdale Capital Management called Northern Dynasty’s plans “worthless,” “a value-destroying boondoggle,” “doomed,” “politically impaired” and “commercially futile.”

“The cash-strapped 100 percent owner’s desperate hope — its 'business plan' — is that the issuance of a permit by the Army Corps will attract new investment, a new partner, or a buy-out,” the NRDC said.

Despite its claims of a “smaller footprint” for Pebble, Northern Dynasty states on its website that its “principal asset, owned through its wholly owned Alaska-based U.S. subsidiary, Pebble Limited Partnership, is a 100 percent interest in a contiguous block of 2,402 mineral claims in southwest Alaska, including the Pebble deposit.”

Every landslide begins with a single pebble.

Building a mine like Pebble (or Donlin) can be compared to building a new Alaska city.

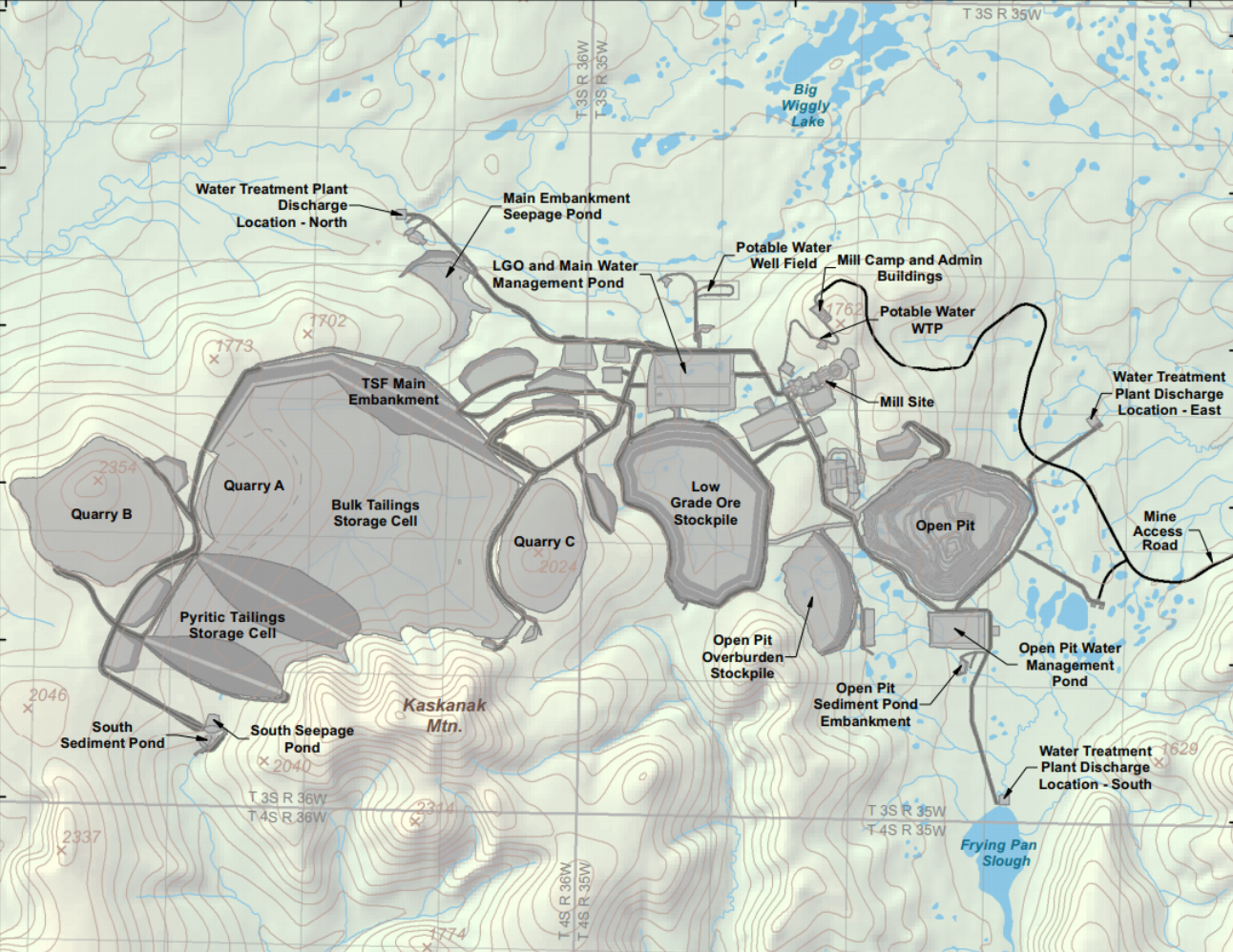

The Pebble deposit lies within a 417-square-mile claim block and will include an open pit, a 550-foot-high tailings dam to hold roughly 30 billion cubic feet of mining wastes forever, overburden stockpiles, quarry sites, water management ponds, milling and processing facilities, a 188-mile natural gas pipeline from the Kenai Peninsula to the site, a power plant, water treatment plants, camp and storage facilities, and an 83-mile road along Lake Iliamna to haul the gold and copper to Diamond Point in Cook Inlet for shipment. (Based on a new “northern route” plan that Pebble opted for a few weeks ago.)

The EPA said in a May 28 letter, “the discharges of dredged or fill material… may well contribute to the permanent loss of 2,292 acres of wetlands and other waters is anticipated, including 105.4 miles of streams, along with secondary impacts to 1,647 acres of wetlands and other waters, including 80.3 miles of streams, associated with fugitive dust deposition, dewatering, and fragmentation of aquatic habitats.”

The tools of the mining trade — hundreds of huge, diesel-fueled bulldozers, blasters, crushers, trucks and other heavy equipment — kick up a lot of dust.

The Army Corps says Pebble will generate nearly 16,000 tons of “fugitive dust” during mining and transports. When it’s blowing in the wind, the dust will carry copper and other particles to thousands of acres of wetlands and streams.

“Increases in copper concentrations of just 2-20 parts per billion, equivalent to two drops of water in an Olympic-sized swimming pool, have been shown to impact the critical sense of smell to salmon which they use to avoid predators and to locate the stream in which they were spawned,” said Thomas Quinn, aquatic and fishery science professor at the University of Washington.

In 2014, the EPA ruled that a large-scale mine like Pebble would be “devastating” to the world’s biggest salmon run and to the region’s culture, and special protections were provided under the Clean Water Act.

The Trump administration removed the protections in 2019, saying the move “pre-empted the permitting process.” It also got a big push from Alaska Gov. Mike Dunleavy, who has made no secret about his support for Pebble. Alaska’s senators and representative supported Trump’s move.

But D.C. can now step aside. The state of Alaska will make the final decision on the mine.

The Pebble applicants do not own the surface rights associated with the mineral claims, and all the lands are owned by the state. Notably, the claim(s) lies within the 36,000 square-mile Bristol Bay Fisheries Reserve, created by voter initiative (70 percent) in 1972 as a way to safeguard salmon from large scale oil, gas and mining projects.

State law requires that the final say on permitting Pebble falls to the Alaska Legislature.

Fish on!