In November 2021, Alaska Gov. Mike Dunleavy created the Alaska Bycatch Review Task Force “to help better understand unintended bycatch of high value fishery resources in state and federal waters.”

He defined bycatch as “fish which are harvested in a fishery but are not sold or kept.”

The 13-member group will issue a final report based on those better understandings in November 2022.

“Once the structure of the task force is framed, it will be a good road map of how we can incorporate everyday Alaskans’ voices into the decision-making process,” said Alaska Department of Fish and Game Commissioner Doug Vincent-Lang in announcing the task force, “because they are the owners of these resources.”

Since January the task force has met online three times and formed four committees and subcommittees focusing on:

- Science, technology, and innovation

- Western Alaska salmon

- Bering Sea and Gulf of Alaska crab

- Gulf of Alaska halibut and salmon

A new public page launched last week via the ADF&G’s site includes the agendas, minutes and audio from all meetings. The reference library also provides presentations by state and federal managers and an overview of genetic stock identification of salmon taken as bycatch in Alaska’s groundfish fisheries.

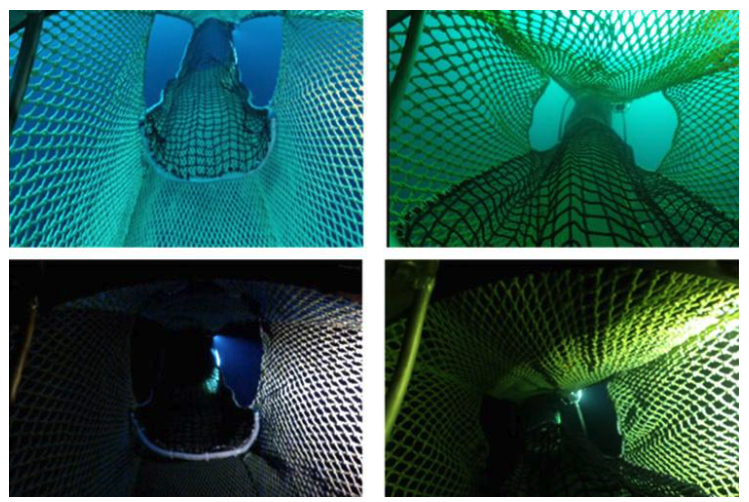

All fisheries are plagued by accidental takes of unwanted species, due to size or being out of season or on a fishing gear’s can’t-catch list. It includes multiple millions of tons of fish and crab that are required by law to be discarded every year.

Alaskan have been angry and frustrated by the federally required waste for decades, but it took last summer’s shutdown of the Yukon subsistence chum salmon fishery to really get people’s attention.

While village smokehouses and freezers stayed empty, trawlers had no limits on their chum bycatch and went about business as usual.

“We have to communicate directly with affected communities,” said task force member Sen. Peter Micciche (R-Soldotna) at the March 9 meeting. “That’s something we have to think about as we develop a product: How we’re going to have two-way communications with the folks that have gotten us to this point where we have a bycatch working group in the first place.”

Providing information that “everyday Alaskans” can understand is critical, said Vice-Chair Tommy Sheridan.

“How can Bering Sea and Aleutian Islands and Gulf of Alaska bycatch reports be more readily available and simplified for public review and understanding?” he said as an example.

Sincerely, good luck with that.

Federal catch accounting is easily available and impressively inclusive. But the data and reports contain a befuddling mishmash of metrics, acronyms and descriptions that are tough to interpret, like this definition:

“Bycatch = Discarded fish. Economic discards: fish harvested which could be legally retained, but are of insufficient value to retain. Regulatory discards: fish harvested which are required by regulation to be discarded whenever caught, or are required by regulation to be retained but not sold. Prohibited Species Catch (PSC): A special type of regulatory discard that must be returned to sea with a minimum of injury = Pacific halibut, herring, salmon, steelhead, king crab, bairdi, opilio crab.”

At least two “listening sessions” are planned, “where all we do is take public comments,” said task force member Stephanie Madsen, director of the At-Sea Processors Association.

The “owners of these resources” will be “incorporating their voices” and asking lots of questions.

Why, for example, are crab considered as prohibited species catch in the Bering Sea but not in the Gulf of Alaska?

And why do managers use a different mix of crab numbers and pounds that don’t add up in bycatch reports?

Why are “other salmon” (chum) considered as prohibited species catch, but have no assigned caps?

If a prohibited species catch cap is reached, managers say a fishery will be shut down. But when Bering Sea trawlers neared their herring cap in 2020, it was quickly doubled by emergency action.

Why were trawlers allowed to exceed their sablefish bycatch limits by 356 and 484 percent in back-to-back years, topping 11 million pounds?

And why is there almost no public information or data on bycatch in state fisheries (out to three miles)?

“This work group was formed because of public outrage at things that may or may not be accurate,” said task force member Brian Gabriel, city of Kenai mayor. “We’re going to spend some time over the next several months providing information that’s more accurate on what’s actually going on and some possible solutions. If we don’t have a way of getting information out, what we’re doing will have very little value to the folks that are the most concerned.”