Scientists are getting closer to understanding how Atlantic bluefin tuna spawn between the Gulf Stream and the continental shelf off New England, possibly a third important breeding area in addition to the Gulf of Mexico and Mediterranean Sea.

The Slope Sea off the Northeast U.S. coast has been studied over the past decade in the belief it contributes to bluefin tuna stock mixing between the two long-known east and west breeding populations.

During summer 2025 scientists with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Northeast Fisheries Science Center conducted two exploratory surveys to examine how bluefin tuna use this area for reproduction. A cooperative survey with commercial longline fishermen sought adult spawning tuna, and a second survey soon after sampled Northeast waters for bluefin tuna larvae.

The researchers’ objective is document how the Slope Sea may contribute to tuna spawning compared to other areas. Their next steps are to analyze genetic DNA from larval and adult tuna to estimate the Slope Sea population size.

“Genetic research has shown the two stocks are interconnected,” according to a summary from the Northeast Fisheries Science Center. “This year’s survey aims to clarify remaining uncertainties about bluefin tuna stock structure and spawning dynamics.”

The reproductive study was conducted by the Large Pelagics Research Center in Gloucester, Mass., which published its first study on potential Northwest Atlantic bluefin spawning in 1999 and multiple follow up studies.

Findings from the study will be presented to the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas in fall 2025. The commission sets total allowable catch limits for each of the western and the eastern stocks of Atlantic bluefin tuna. ICCAT annual decisions affect how much tuna fishermen from all of the Atlantic nations are allowed to catch, and debates over the science of spawning areas has raged for 40 years.

In earlier years, “sampling of the Slope Sea was piggybacked on other surveys, limiting the number of bluefin tuna larvae we could collect,” said Dave Richardson, a lead scientist on the project who has been investigating the Slope Sea tuna area for a decade. “Our goal this year was to collect as many larvae as possible. We intend to provide these larvae to multiple research groups that are using independent approaches to evaluate linkages among spawning grounds.”

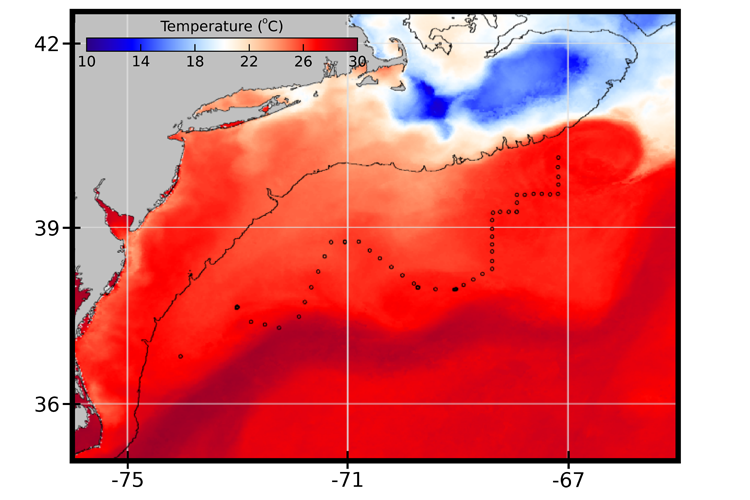

The scientists used the same fishing tactics as bluefin tuna anglers, focusing on ocean conditions where sea surface temperature, currents, and sea surface salinity to determine where they would be most likely to find larval bluefin. With 70 net tows through the top 20 meters of the water column, scientists found larvae at more than half of the stations.

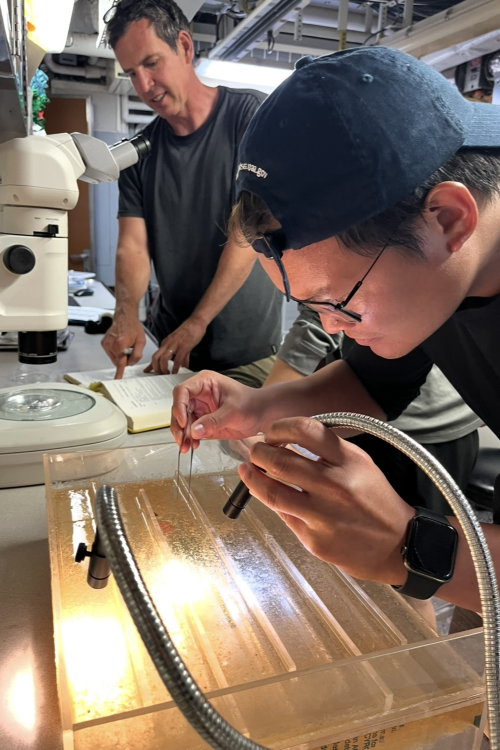

“We got a substantial number of larvae, which we are very excited about!” said Kristen Walter, a researcher with NOAA’s Southeast Fisheries Science Center and the University of Miami Cooperative Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Studies. “Now it’s just a matter of going through the samples, identifying the bluefin, examining size ranges, and doing genetic testing to determine our findings.”

“Ultimately, this effort will help us understand how bluefin tuna use the Slope Sea for spawning, and the resulting impacts on population dynamics. That’s a huge question for tuna anglers. But finding larvae is just one piece of the puzzle. The bigger question is: “What is the stock structure of Atlantic bluefin tuna?”

A key component is “exploring the application of modern genomic techniques to improve fisheries data quality and efficiency,” according to Matt Lauretta, one of the lead researchers on the bluefin effort. “Ultimately, these data can be used to determine the contribution of the different bluefin stocks to the fisheries and estimate total abundance so we can get a better handle on how many bluefin are out there to catch.”

Full results from genetics and modeling could take several years. Yet the Slope Sea 2025 research cruise “itself is a significant step,” according to the Northeast science center’s summary. “The project also emphasizes the importance of collaboration. NOAA scientists are supporting partners at the University of Maine’s Pelagic Fisheries Lab and anglers up and down the Eastern Seaboard who are expanding citizen science efforts for bluefin tuna. Through this collaboration, tuna anglers can request fin clip kits and biopsy punch tools to collect DNA tissue samples to better understand bluefin tuna genetics and stock mixing.”

“We hope this work can help answer the questions many fishermen have about what’s going on with bluefin," said Clay Porch, director of the Southeast Fisheries Science Center. “There's a strong perception among fishermen that bluefin tuna abundance is higher than it has been in a long time, leading to calls for increased quotas.”

Results of this research will be presented at the annual International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas in fall 2025. ICCAT sets a separate Total Allowable Catch for each of the western and the eastern stocks of Atlantic bluefin tuna through a management procedure that uses several indices to track the abundance of both stocks, with the total allowable catch for each stock going up or down depending on the indices.

The first management procedure was adopted in 2022. It is scheduled to undergo review, beginning in 2026 and ending in 2028, to update it with new information. ICCAT will also undertake a status assessment – a health check of the stock, in 2026 to evaluate whether management is working as intended.

“We anticipate that the Slope Sea larval survey and the collaborative longline survey will both play an important role in these processes, providing data that have never been available before,” according to the Northeast science center.