The Biden administration and coastal state governments are banking intensely on offshore wind energy as the long-term solution to reducing carbon emissions and solving the problems of siting new power facilities on shore.

Michael Shellenberger says it’s time to go back to the land — and nuclear power.

“If you really care about climate change, we’d be doing more nuclear power,” said Shellenberger, a longtime environmental writer and founder of the nonprofit think tank Environment Progress, at a July 15 speaking event hosted by opponents of offshore wind with the Save Our Shoreline group in Ocean City, N.J.

New Jersey Gov. Phil Murphy last week signed legislation to quash Ocean City officials’ intent to block power cables coming ashore from Ørsted’s planned Ocean Wind project. Murphy and powerful Democratic leaders in the state Legislature who advocate developing that and other turbine arrays say they won’t allow local governments to derail the state’s renewable energy goals.

Shellenberger said New Jersey and other states already have options at hand to reduce carbon emissions — by maintaining and redeveloping power plants from the heyday of the U.S. nuclear industry.

“Wind uses significantly more” concrete and steel than building natural gas and nuclear power stations, Shellenberger told a receptive audience of about 150 in the Ocean City Music Pier.

For projected power output from Ocean Wind, Ørsted and state officials “say 500,000 homes. That right there is misleading” because the number represents potential and not the varying nature of wind power, he said.

For a comparable and steady power supply, “half a (nuclear) reactor” would suffice without occupying the square miles of sea envisioned for the Ocean Wind and neighboring Atlantic Shores project, said Shellenberger: “You could add a reactor and not need that wind farm-times-two… you could just add another reactor to an existing site.”

Shellenberger is a prominent figure in what has been called the ecomodernist movement — intellectuals who recognize threats to the environment but believe society will overcome them with technology.

Shellenberger is the author of the book “Apocalypse Never” published by Harper Collins in 2020, summarizing his views from the viewpoint of an “environmental humanist” recognizing global progress since the 1970s. In 2003 he was a co-founder of the Breakthrough Institute, a think tank committed to technological solutions to environmental problems and “energy poverty,” and more recently founded Environmental Progress.

Dismayed by the prevalence of catastrophic rhetoric in the environmental movement, Shellenberger has won praise for his critiques from other advocates. But some of those colleagues have backed away, put off by Shellenberger’s downplaying of climate change effects.

“I think climate change is real,” Shellenberger told the Ocean City audience, but added that “sea level rise is the climate change impact I worry least about.”

Looking to the Netherlands as an example, he argues that “we’re going to be able to adjust to that.”

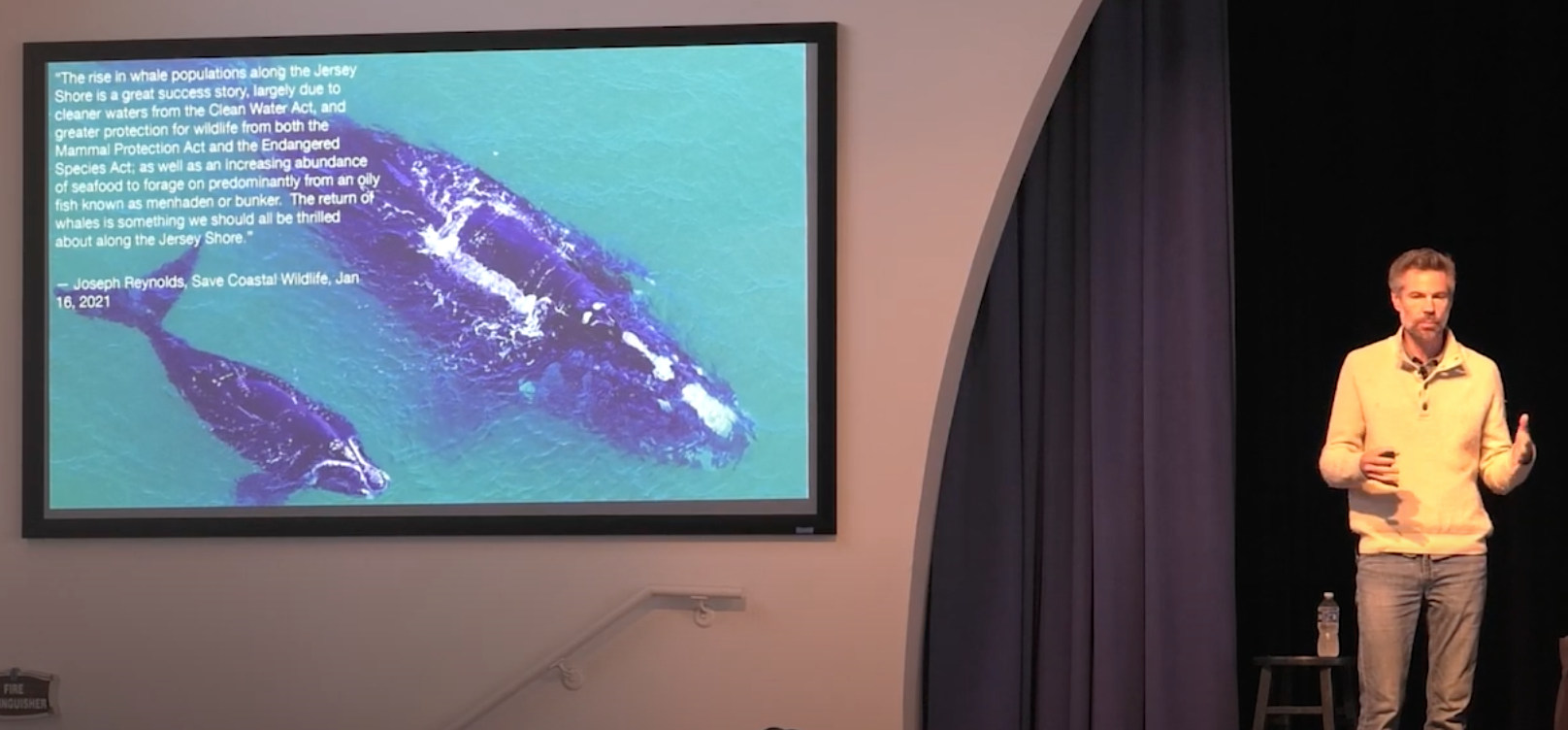

One focus of the Save Our Shoreline group has been the highly endangered northern right whale population that migrates past planned wind energy areas in the New York Bight.

The drive to develop East Coast wind energy will bring construction and undersea noise “from Maine to North Carolina. It will probably go on for decades,” organizer Tricia Conte said in an interview. “I don’t see how those under-400 animals are going to survive this.”

After a morning spent with his hosts on a whale-watching vessel, Shellenberger laid into the subject in his talk. Beyond direct impacts from wind farm construction and operation, any losses to the right whale population would have consequences for the commercial fishing industry, already under intense pressure to end gear entanglements with whales, he said.

“You can’t just go and add another significant impact to the species,” he said.

Sponsors of the event included the industry group Garden State Seafood Association and New Jersey-based surf clam and scallop operators: Lund’s Fisheries, LaMonica Fine Foods, Sea Watch International and Atlantic Capes Fisheries.

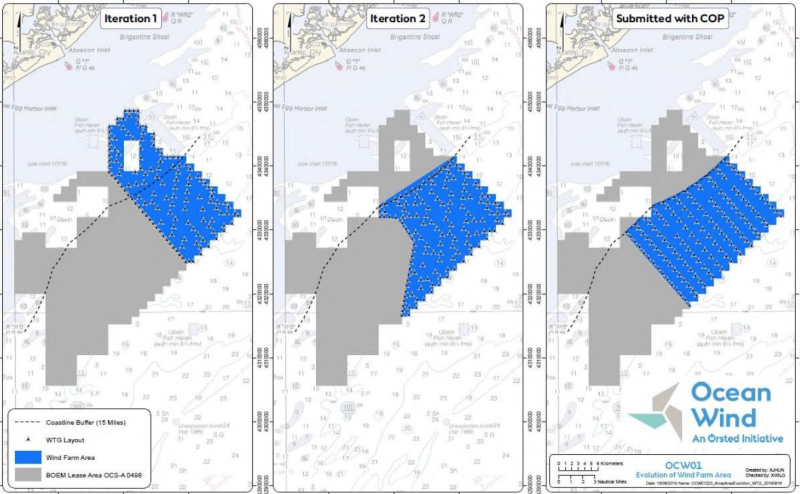

Ørsted has made changes to its planned Ocean Wind layout in response to fishermen’s concerns, and the developers must address other environmental issues, so “it is not a done deal at all,” Shellenberger told the audience.

“There’s much more you guys can do,” he added to cheers and applause. “There’s no reason this project can’t be wiped right off the drawing board.”

It was one week before Murphy signed the measure to head off any move by Ocean City officials. City Council vice president Michael DeVlieger told the audience he’s prepared for a long struggle, after a city delegation met with state lawmakers.

“The message that was really driven home to me was, ‘You’d better get ready, because this is coming,’” he said.