Fate brought Mark Vrablic to Wanchese, N.C., at a young age. He grew up in the Etheridge family – more specifically, he grew up in the Willie R. Etheridge Seafood Co. Established in 1936, the Etheridges’ fish company has seen decades of history in southeast and Mid-Atlantic fisheries.

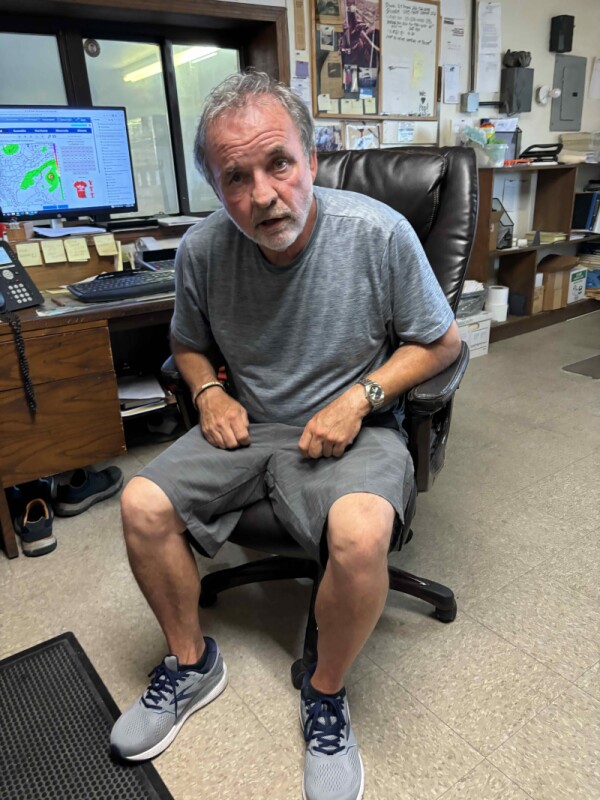

On a hot August afternoon, Vrablic, now manager of Etheridge Seafood, is sitting upstairs in his office, contemplating the past and the future and how he can help keep the North Carolina commercial fishing industry alive and healthy. “I ain’t got time, buddy,” he says when I first arrive. “Come back when I got some boats in and I’m in a better mood.”

But Vrablic is always ready to fight for the industry he’s given his life to. As soon as he answers one question, he’s engaged and telling the story of change on the Wanchese waterfront, a story he hopes the Willie Etheridge Seafood Company will survive.

Next to Etheridge Seafood stand the buildings of the Wanchese Fish Co. “Cooke bought it,” says Vrablic. “The Corps of Engineers won’t let us dredge more than 9 feet, and Cooke can’t get their boats in here. So, they’re selling it.”

As Vrablic describes it, the issue is real estate. “They want this for development,” he says, noting that the waterfront has become more valuable as a place for vacation homes than for fishing boats. “There is too much wealth here, and it’s killing us. They’re not going to say it, they’ll never tell us we can’t fish, but things are getting so hard we can’t make a living anymore.”

Vrablic understands the economic value of the recreational fisheries. “But one man’s pleasure shouldn’t take another man’s livelihood,” he says. “Is the ocean going to be a playground for some, or a source of food for us all?”

Like many others, Vrablic sees the U.S. paying to help other countries develop shrimp farms that produce low-priced products often contaminated with antibiotics and other chemicals.

“They have ships full of shrimp in our ports that are four months out from getting unloaded. That’s why the tariffs ain’t making no difference,” he says. “These guys come in with big trips of shrimp, 13,000 pounds, but they’re getting a dollar less a pound than I got in the ‘80s.”

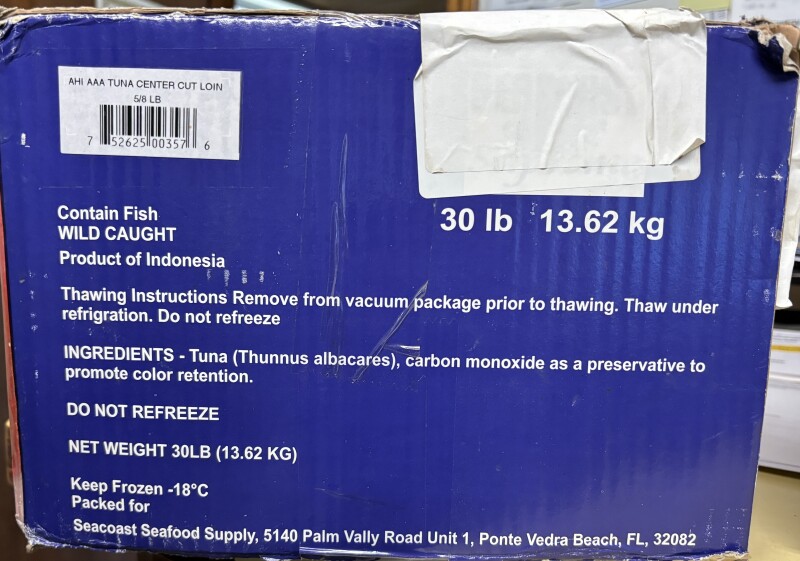

The flood of imported farmed shrimp, often contaminated with chemicals and antibiotics, has long been an issue of contention for the U.S. fleet. “It’s not just shrimp,” Vrablic says. “Let me show you something.” He holds up a box with the label that says: Ahi Tuna, product of Indonesia, treated with carbon monoxide to promote color retention.

“They don’t have to tell you that it’s treated when they sell it, but by law, they have to put it on the master box.” Then he hands me a photocopy of an article from the New York Times that says: “Japan, Canada and the European Union have banned [carbon monoxide] because it can mask spoiled fish.”

“Real tuna is a darker color, not this bright pink red,” says Vrablic. “With carbon monoxide, you could have fish that the flies wouldn’t eat, and it would still look fresh.” He tosses the box aside. “That came out of the dumpster of a market that used to buy a lot of tuna from me. They haven’t been buying as much. Now I know why.” And ahi? “There is no species of tuna called ahi. It’s a Hawaiian name used for marketing. It’s a name for bigeye, skipjack, and yellowfin tuna.”

This is what U.S. fishermen are up against, Vrablic points out: cheap, often contaminated, imports.

“In all the years since Willie Etheridge started this company, millions of pounds of seafood have come across this dock to feed the people who can’t afford a recreational boat to go catch their own, and none of it has had one spoonful of chemicals added to it. It’s the most natural food you can get, and Americans need to know that.” He adds that it’s a matter of food security. “Look what we saw during covid. Where are you going to get your fish if supply chains break down? You’re going to get it right here.”

Hanging on the walls of Vrablic’s office are photos and newspaper clippings of the glory days. “These are the last three commercial boats built in Wanchese,” he says, showing me a photo of three 80-foot boats rafted together. “That was 1983. Back then, if you were a fisherman, you were somebody,” he says. “Now?” He throws up his hands.

As Vrablic sees it, fishermen need to reclaim their place as valued food producers for US consumers. “The only way we’re going to win is if this administration gets out there and exposes what is in the seafood we’re eating,” he says. “That would put American fishermen back on top.”

Vrablic believes that if people like the U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services, Robert F. Kennedy Jr., are really on a mission to make America healthy again, they will start to amplify the story he is telling.

“The American people need to know that they could be eating the best, most natural seafood in the world. We have it right here. But one out of ten restaurants will buy our fish. The rest will buy the carbon monoxide-treated tuna and imported shrimp because it’s cheaper.”

Vrablic believes that the U.S. should take a cue from other countries and ban adulterated seafood. “The Japanese, the Canadians, the Europeans – they live longer, they’re healthier – and we wonder why. It’s because they won’t accept seafood with chemicals and additives.” He argues that if the Kennedy starts telling Americans about the high quality seafood that American fishermen are landing, along with its health benefits, people will start to demand domestic seafood, and they will start to value fishermen and working waterfronts.

“We need to go public with what’s in the imported seafood,” he says.

Vrablic tells a story of being in a store that was advertising fresh tuna and sending his wife to ask if it had ever been frozen or treated with anything. “I told her to tell them she might have an epileptic fit if it has. They told her not to buy it.” Vrablic and many others argue that if U.S. consumers are going to pay premium prices, they should be getting premium products.

But while Vrablic's focus is on imports and keeping the fish that comes across his dock free from additives, some domestic seafood is also treated with chemicals, such as sodium tripolyphosphate. Although approved by the Food and Drug Administration, sodium tripolyphosphate is a registered pesticide that is used to increase the weight and appearance of some types of seafood, particularly shrimp and scallops.

“We don’t use that,” says Vrablic, when asked. “What’s the point? You pay less, but when you cook it shrinks back down, and you get less.”

In Vrablic’s view, the only way for fishermen to regain their status and profitability in the country and coastal communities is for Americans to realize that domestic seafood is a national treasure upon which their health and food security depend.