The search for critical minerals could put deep-sea mining and commercial fishing on a collision course.

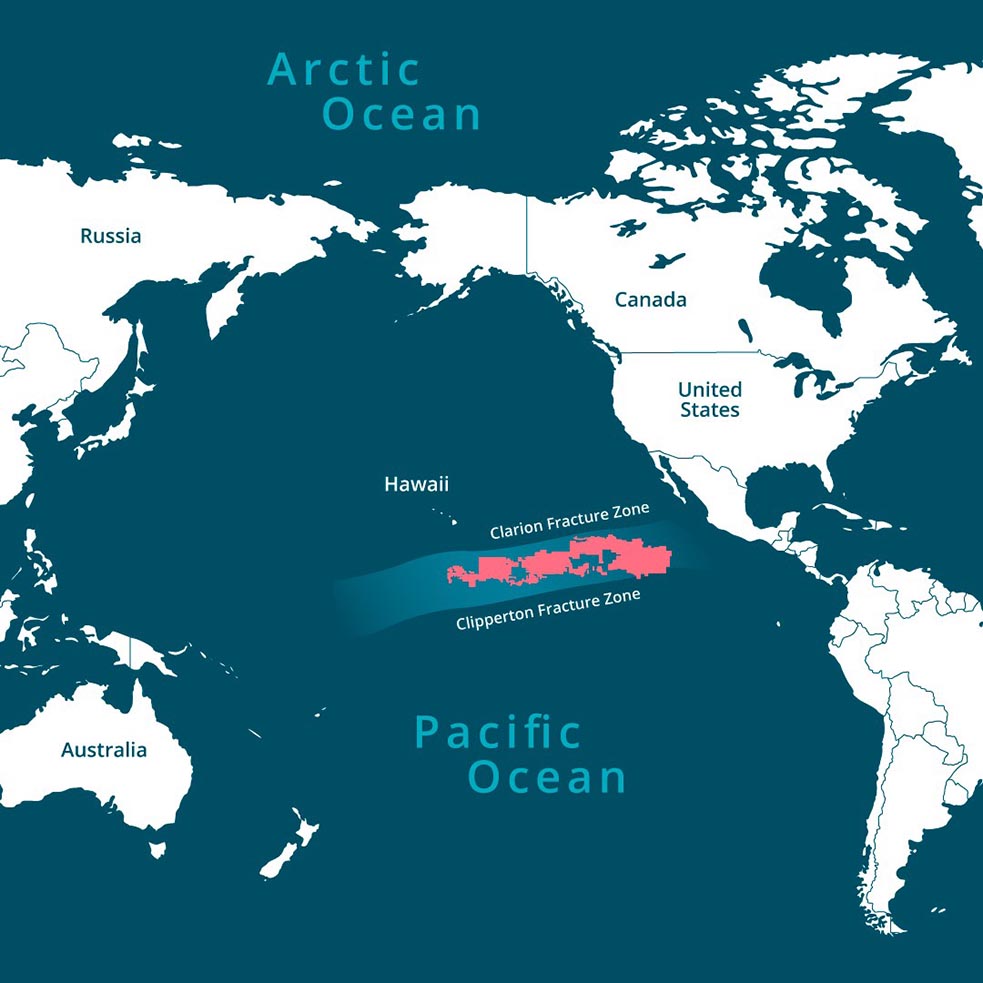

In 2023, a study published in Nature Magazine predicted a collision between Pacific tuna fleets and deep-sea mining interests as both converged on the Clarion Clipperton Zone (CCZ), a 1.7 million square mile region between Hawaii and Mexico. Lead author Dr. Diva Amon and her colleagues predicted that global warming would drive tuna, particularly yellowfin, bigeye, and skipjack, to seek refuge in the cooler waters of the CCZ. At the same time, countries and companies from around the Pacific Rim and beyond are eager to conduct deep-sea mining in the CCZ, and President Trump signed an Executive Order on April 24, 2025, aimed at “revitalizing American dominance in deep-sea minerals.”

The existence of rare earth minerals in the CCZ has been known since 1873, when the British research ship HMS Challenger hauled up polymetallic nodules laden with manganese, copper, cobalt, and more. Since 1994, the International Seabed Authority has regulated deep-sea mining in areas outside any national jurisdiction as part of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). The Authority currently has contracts with 17 companies to explore mining in about 500,000 square miles of the zone. While there is no active mining in the Clarion Clipperton Zone yet, all contract holders are undertaking geological and environmental studies as part of their contractual obligations to determine the feasibility and impacts of deep-sea mining.

Peter Webster, of Honolulu, Hawaii, owns two tuna boats, the Pacific Sun and the Itasca. He fishes the western end of the CCZ and is skeptical of what mining could do to the fishery.

“We fish about 900 miles from Honolulu,” he says. “A lot of times a big cold water bubble will come up in there from the southwest and create temperature breaks—those are good places to look for fish. I don’t know much about the mining, I haven’t seen any of the ships, but I can’t imagine it’s going to be good. Those are very fragile habitats.”

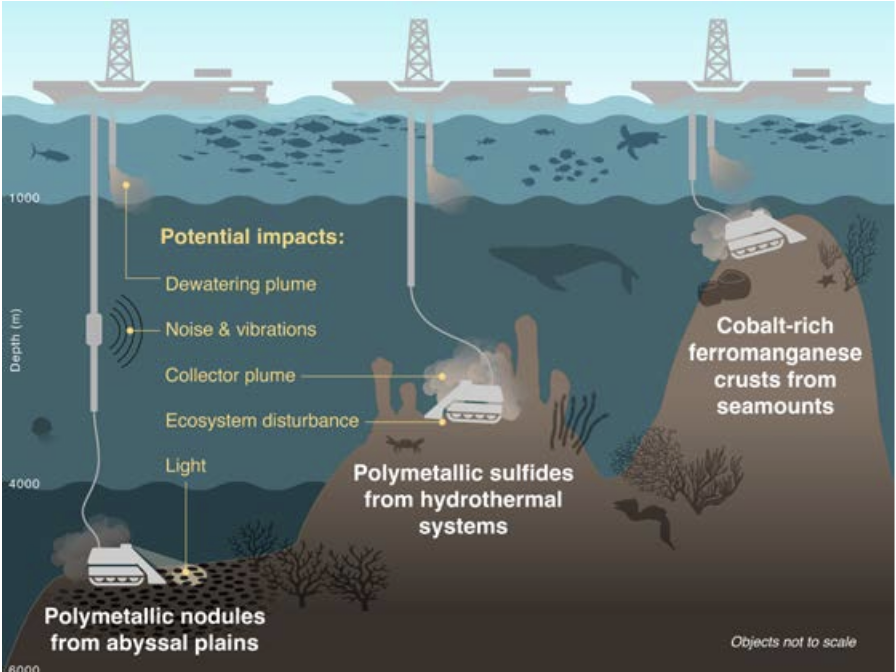

Like many others, Webster wonders if the mining will upset the natural cycles of upwelling, how the plumes of debris from the mining will affect the seafloor, and how the secondary plumes from mining vessels will affect primary production near the surface.

"Our fishery is a model for sustainability,” Webster says. “We have 140 active permits. We are closely monitored and even our crews are being schooled in how to reduce negative impacts on birds and cetaceans.”

Webster has fished in or near the CCZ since the 70s, when he was just a kid on his father’s boat, and like many others, he advocates a pause on mining. “There’s a lot we don’t know about how all these systems interact,” he says.

"He’s right,” says researcher Dr. Amon. “There are many ways that mining could affect the ecosystem. The operation would generate two plumes of discharge, one where nodules are collected on the seafloor and another where wastewater and fragmented material containing high levels of toxic metals are discharged into the ocean from the surface mining vessel. All of these could disrupt tuna behavior and potentially lead to the bioaccumulation of toxic metals in prey species and, consequently, tuna.”

Dr. Amon notes that noise and concentrations of mining vessels could also alter tuna behavior and constrain fishing operations, and she points out that she and others are just scratching the surface of the CCZ. “We only have enough science to make management decisions for 15 percent of the zone,” she says. “And we know that there are vertical linkages between what happens on the bottom and how it affects the water column all the way to the surface, as well horizontal linkages to surrounding areas. What we don’t know yet is how they work.”

Dr. Amon adds the nodules being collected also provide habitat for 50% of the species she and her team have observed.

During one of the world’s first deep-sea mining pilot tests conducted by Global Sea Mineral Resources (GSR), a subsidiary of the DEME Group, in 2021, a three-mile-long cable parted and left GSR’s 25-ton nodule collecting robot, the Patania II, stranded on the bottom in the CCZ.

GSR eventually recovered its machine, but independent scientists monitoring the Patania II’s effects on the seafloor found a number of negative impacts on the sediment and ecosystems — “which supports the hypothesis that nodule collection by PATII removed the ecologically important bioactive surface layer,” a team of scientists said in a study published in Frontiers of Science.

“Besides this seabed alteration, impacted areas also experienced sediment blanketing… Collector-induced sediment blanketing occurred in adjacent areas outside the Collector Impact area, with sediment deposition up to 3 cm. These Plume Impact sediments exhibited lower food availability, and further research on the plume composition’s role in biogeochemical processes is needed,” the scientists concluded.

While the International Seabed Authority continues to pour through the increasing amount of data in its painstaking work to develop mining regulations that protect the region’s ecosystems, many countries are calling for a moratorium on deep sea mining development. But that isn’t stopping The Metals Company, a Canadian mining company that in early 2025 announced its plan to seek a U.S. permit to operate in the CCZ.

The U.S., along with 14 other UN member states, has not ratified UNCLOS and continues to regulate deep sea mining, including mining in areas beyond national jurisdiction (ABNJ), under the 1980 Deep Seabed Hard Mineral Resources Act (DSHRA). According to a White House fact sheet, President Trump’s executive order “instructs the Secretary of Commerce to expedite the process for reviewing and issuing exploration and commercial recovery permits under the Deep Seabed Hard Mineral Resources Act.”

Administered by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the DSHRA combined with the executive order could open a path for The Metals Company to begin deep sea mining in the CCZ, provided the company can comply with relevant provisions of the Jones Act.

"I can't speculate on how the Jones Act may affect the process. NOAA doesn't enforce the Jones Act,” says NOAA spokesperson Maureen O’Leary. “The Metals Company issued a press release stating that it intends to apply for an exploration license and permit but to date, we have not received either.”

According to a NOAA statement provided by O’Leary, “Under the U.S. Deep Seabed Hard Mineral Resources Act, U.S. companies can apply for exploration licenses and commercial recovery permits for deep-sea mining in ocean areas beyond national jurisdiction. NOAA's National Ocean Service reviews these applications for compliance and requirements in accordance with the act and regulations. The process ensures a thorough environmental impact review, interagency consultations, and opportunity for public comment. Licensing and permitting involve a multi-step process before any exploration activities or commercial recovery can occur.”

In 1984, NOAA issued four exploration licenses for locations in the CCZ, two of these were surrendered and two ended up in the hands of Lockheed Martin Corporation, which sold them to a Norwegian startup, Loke Marine Minerals, that declared bankruptcy on April 3, 2025.

While the current focus is on the CCZ due to its abundance of polymetallic nodules, it isn’t the only place where U.S. fishermen may find themselves interacting with deep sea mining. A NOAA research cruise in 2021 found extensive ferromanganese nodules covering a chain of seamounts extending out from New England into the North Atlantic, and although NOAA regulates the DSHRA, the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) and the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) work with the agency and have identified areas of the U.S. outer continental shelf (OCS), where rare earth minerals might be found at levels worthy of exploration and possible exploitation.

"BOEM has funded several offshore critical mineral assessment projects on the OCS. In the Pacific, these projects included sites located off the western Aleutian Islands, offshore of Alaska, and in the Escanaba Trough, offshore of California, areas north of Puerto Rico, areas around Hawaii and the U.S. Pacific Island territories (e.g., American Samoa, Guam, Northern Mariana Islands), and the Gulf of Mexico for sites with potential for critical minerals,” notes a congressional research publication.

President Trump’s executive order also “directs the Secretary of Interior to establish a process for reviewing and approving permits and granting licenses within the U.S. Outer Continental Shelf under the Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act.”

In order to understand how deep sea mining can affect the seafloor, in 2022, NOAA, the USGS and BOEM surveyed a region off the coast of Georgia where a private company, Deep Sea Ventures, experimented with deep sea mining in the 1970s. “These new data enabled the partners to confirm that evidence of bottom disturbance from 1970 was both widespread and definable across the study area,” says the report from that study. “BOEM and the USGS will further analyze these data to quantify the extent of the impacts, search for visual signs of ecosystem recovery, plan for additional research, and, ultimately, inform reviews, future decisions, and mitigation measures related to deep-sea mining in other areas.”

To date, BOEM has not issued any leases for critical mineral exploration and development. Nonetheless, deep-sea mining, offshore aquaculture, oil and gas exploration, and other marine industries are all aspects of the “blue economy” currently being promoted by the U.S. and almost all other coastal nations.

"Humans are pushing more and more into the deep ocean,” says Dr. Amon. “If we continue, we will see more and more conflict with these industries.”