The Bristol Bay Regional Seafood Development Association (BBRSDA) and the University of Washington Alaska Salmon Program hosted a webinar on Thursday May 5th to present the 2022 salmon forecast as well as ongoing research into run timing, environmental impacts, and fish and climate trends in the bay.

Founded in 2005, the BBRSDA is an organization established by Bristol Bay fishermen to support all aspects of the sockeye salmon fishery from marketing to infrastructure to research and education. The UW Alaska Salmon Program focuses its research on the Pacific salmon fisheries of Alaska in an effort to gain understanding of the changing ecosystems and provide knowledge necessary to management and conservation. According to Michael Jackson, president of BBRSDA and thirty-year Bristol Bay fisherman, the scientists presenting as a panel in this webinar, “...translate scientific research into practical application...to keep Bristol Bay the most sustainable fishery on the planet.”

Chris Boatright, project manager and research scientist for UW, started the panel off with his presentation of the 2022 forecast for Bristol Bay sockeye and a brief overview of the trends that have been observed in recent runs. The forecast for the upcoming season is the largest ever seen at 71.91 million fish. This translates to an approximate harvest of 52.4 million fish after accounting for escapement and the South Peninsula catch.

However, the forecast has been low in recent years and Chris explained that they have seen, “much greater than expected 1.2 returns,” and that this has been occurring in different river systems each year and has contributed to under-forecasting. (1.2 is an age notation used for sockeye meaning one year in fresh water, and two in salt water.) These 1.2 returns have been considered in this year’s forecast in rivers like the Nushagak and Wood, which have been among the highest-producing river systems and are forecast to perform similarly this year. Chris noted that this behavior, “generally has to do with very climate-driven growth.”

Daniel Schindler, also of the UW Alaska Salmon Program, picked up where Chris left off discussing this “climate-driven growth,” and its correlation to the large returns of recent years. He explained that the, “warmer sea surface temperatures translate to bigger returns,” when smolts are encountering them in Bristol Bay, despite the fact that they, “correlate to disastrous returns elsewhere,” referencing the Gulf of Alaska where the sea surface temperatures are already warmer than those in Bristol Bay. He mentioned the strong La Nina that has been observed in the last couple of decades as a factor and said that as the climate warms, so do the lakes and the bay, leading to higher smolt survival. When asked about a tipping point where the sea surface temperature begins to cause a decline in survival rates, as has been seen further south, he didn’t have a definitive answer as to when that would occur.

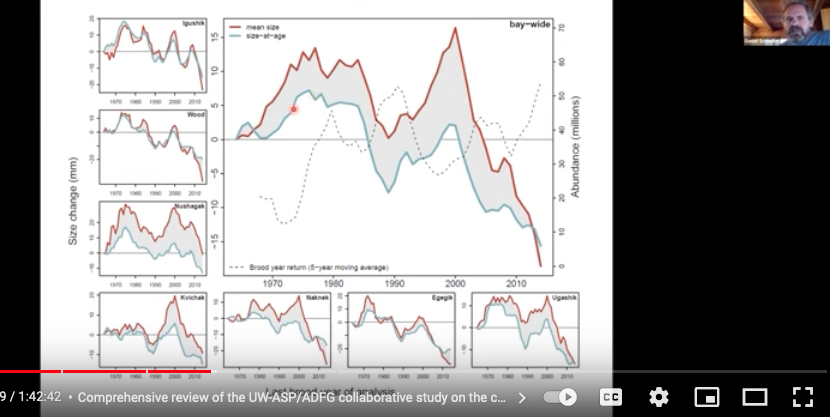

These warmer sea surface temperatures have not only been beneficial to the survival rate of the sockeye, but also to that of the pinks and chum in the bay. Competition for the food that they all share is fierce and Daniel said that, “the build-up of hungry mouths is as high as it’s ever been.” Many of those fish are hatchery-produced, and the high survival rates of those fish are aiding in the declining body size of the sockeye that has been seen since 1980, and has been accentuated in the last five to ten years, according to Daniel. This change in size is in large part due to a slower growth rate, and not the change in age of returning fish explained earlier by Chris. Daniel made it clear that in addition to a large run, “we should be expecting a lot of small fish this coming summer.”

When the bulk of that run will be happening falls under the purview of Curry Cunningham, a former fisherman working with the BBRSDA and conducting research into run timing and how we can use machine learning to predict whether the run will be early or late in any given season. This is classified based on the date at which fifty percent of the season total catch and escapement has arrived inshore. Run timing affects the ability to predict a run size in season and Curry notes that this is, “highly variable over time,” and is researching, “...whether or not there are environmental conditions that are linked to run timing.” He says that there are many factors to take into account and it is important to attempt to discern which indicators are important when predicting run timing, and how reliable they are. Run timing has been, “highly variable over time,” however high abundance years have typically coincided with later run times. His graph of last year’s run timing also shows that the midpoint occurs on different dates in each district, with Nushagak having the earliest run, and Togiak having the latest. His work is ongoing and takes into consideration everything from ice pack to precipitation to sea surface temperature. The hope is that this research can lead to a complex data compilation method that will help fishermen, canneries, and scientists better prepare for the season.

Ray Hilborn, with UW Alaska Salmon Program, ended the webinar with an interesting presentation comparing the environmental impact of sockeye salmon with that of Atlantic farmed salmon measured in kilograms of CO2 emissions created in the production process to kilograms of product. (He also compared the impact of an IMPOSSIBLE Whopper versus a sockeye salmon sandwich, showing that 1.7kg of CO2 per kg of product is created in the production of a sockeye sandwich to the IMPOSSIBLE Whopper’s 3.5 kg of CO2. The sockeye has less environmental impact by more than half.)

Ray addressed the contributors to the environmental footprint of sockeye salmon which include every step of the production process from the boats and tenders, to the canneries and transport to a final buyer. He pointed out that overall the fuel use for the Bristol Bay fishery is much lower than the existing literature on commercial fisheries and that, in comparison to Atlantic farmed fish, the fishery has a much lower impact in terms of kilograms of carbon dioxide produced per kilogram of product.

Other environmental impacts that Ray touched upon included nutrient release, ecotoxicity, and land use. He noted that in each of these areas fisheries are always very low, and that in the case of farmed fish, which have very high impacts, it is the growing of crops for feed that has the most impact, from fertilizers, pesticides, and extensive land use. His color-coded graphs spoke for themselves when he compared sockeye with the farmed fish and the impact of the former was barely discernible in comparison to that of the latter.

Ray concluded his presentation by stating that, “[sockeye is] one of the most environmentally friendly forms of food that we know,” and that, “a kilogram of sockeye is lower [in impact] than a kilogram of corn.”

Click here to watch the full webinar.