Washington’s Taylor Shellfish Co. hasn’t let exponential growth alter the family flavor

Riding south on I-5 from Seattle to Tacoma and then west through Olympia to Shelton, Wash., with “Oyster Bill” Whitbeck, the early-morning sun flashes between towering Sitka spruces, growing so close together their bare trunks create a shoreside fence of evergreen pickets stretching skyward to conical tufty tops.

In just under two hours, we pull into the lot in front of Taylor Station, our commute dropping us at the diner just after the morning rush. We have our choice of tables, but our order is almost preordained. It would feel foolish to order eggs Benedict when Oyster Bill says the razor clam breakfast is the best thing out of the kitchen. (Read more about my trip in "Shell life.")

For the last 15 years, Whitbeck has managed direct restaurant sales for Taylor Shellfish Co., headquartered in Shelton. In researching his book “Joy of Oysters,” Whitbeck discovered “a pain point for chefs who didn’t want to work through a distributor to source oysters.” He went to work for Taylor, selling live oysters in farmer’s markets in 2002. That grew into the company’s direct sales division, which now sends three trucks six days a week to about 200 restaurants in the Seattle area and recently expanded down into Portland, Ore.

Like many other of the moving parts of this vertically integrated company, the restaurant sales grew organically from a need and a workplace that thrives on innovation and customer service.

This feature was first published in the September issue of National Fisherman. Subscribe to the magazine to be the first to read NF cover stories.

But Taylor is no one-trick pony. It’s called a shellfish company because they do it all — clams, geoduck, mussels and oysters, lots of oysters. But the message Taylor Shellfish sends, despite the fact that it is the largest shellfish company in North America, is that quality is the top priority.

“We don’t always have the cheapest oysters on the market, but we want them to be the best quality,” says Audrey Lamb, biological project manager.

The first of the Taylor family to settle in Washington was J.Y. Waldrip, who left a ranching gig with Wyatt Earp in Arizona in pursuit of Klondike gold and eventually settled in Olympia in the 1880s. Waldrip fell in love with shellfish farming in Puget Sound, and now the family has been working the flats in western Washington for nearly 130 years. They incorporated the bivalve business (now employing a fifth generation of Taylors and spouses) in 1969.

The family’s fourth generation (Waldrip’s great grandsons) mans the helm of the shellfish company, which has bloomed over the last 20 years with the boom of demand for oysters.

Paul Taylor oversees the farming division, including hatcheries and nurseries, essentially seed to harvest. Bill Taylor is responsible for public affairs, public relations with the community, political outreach and also oversees the relatively new Canadian operation of Fanny Bay Oysters out of British Columbia. Jeff Pearson, brother-in-law to Paul Taylor, runs processing, sales and retail.

“One thing the fourth generation has instilled is they’re not afraid to take risks,” says Marcelle Taylor Gonzalez, marketing manager and member of the fifth generation as one of Paul Taylor’s daughters.

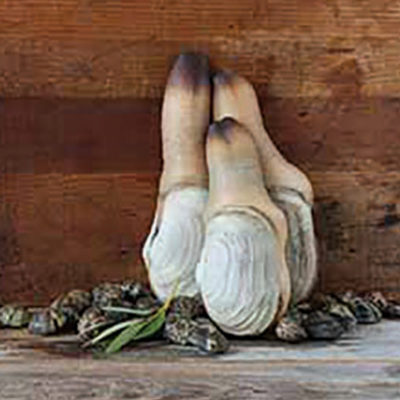

Taylor grows, sells and serves oysters, geoducks, clams and mussels. Taylor Shellfish photo.

That was apparent when the fourth generation decided to take the leap from wholesale and direct sales to carving out their own niche in the restaurant business. And not just any restaurant — raw bars, which offer the added complexity of a very short shelf life for the primary product.

In 2013, Gonzalez and her now-husband, Xadier, relocated to Shelton from Los Angeles, where she had been working in corporate franchising, to help launch the oyster bar project. Taylor opened its first two bars the following year. Two more have followed in Seattle, with another to come, and one in Fanny Bay, British Columbia.

The restaurants and retail shops alone would amount to a successful business, as would the direct sales to more than 200 local restaurants. But they’re only a sliver of Taylor Shellfish.

“Our oyster bars make up a very small portion of the business, but they’re big visibility for us,” says Gonzalez. “They’re our face, essentially. Our visibility has increased significantly over the last maybe seven years.”

The company sells to distributors and restaurants around the world, but it also has its own hatcheries in nearby Quilcene as well as Kona, Hawaii; two local upweller sites to nurture the oysters from seed to plantable sizes; farm flats all over Puget Sound (and more recently in British Columbia’s Fanny Bay), about 50 in all; two processing facilities in Shelton — one for the company’s four types of oysters and one for the clams, geoduck and mussels; — and another in Willipa Bay; a trucking service that drives product around the region; catering; retail markets on site in Shelton and British Columbia; and even a fabrication shop, which builds everything from boats to cages.

“We grow our shellfish from tide to table,” Gonzalez says. Taylor employs about 500 people, including the crews who work the flats in groups of four to 20.

“We’re a shellfish farming company first and foremost,” says Gonzalez. “Ninety percent of the product sells wholesale.”

The company delivers about 50 million live oysters a year, 150,000 gallons of shucked oyster meat, about 5 million pounds of clams, 1.25 million pounds of mussels and 750,000 pounds of geoduck.

The shell squad: Taylor’s lineup includes four varieties of oysters in varying sizes, clams, mussels and geoducks. They also grow and sell Virginica oysters for their oyster bars.

- Kumamoto Crassostrea sikamea These small oysters were introduced to Washington from the Kumamoto prefecture in southern Japan in 1947. They have a deep cup with a sculptured fluted shell.

- Olympia Ostrea lurida Often called Olys (OH-leez), these oysters are native to western North America. Smaller than a 50-cent piece, they were the favorite of 1870s gold miners in California.

- Shigoku Crassostrea gigas Shigoku means “the ultimate” in Japanese. This tide-tumbled oyster may be the most popular in the world. The rise and fall of Northwest inlet tides tumble the crop twice daily in float bags, creating a deep shell.

- Pacific Crassostrea gigas Market size for Pacific oysters ranges from a 2- to 3-inch extra small to the 5-plus-inch large. The meats vary in color from white to chestnut brown with gray to bright black mantles.

- Mussels Mytilus galloprovincialis The Mediterranean mussel was introduced to the U.S. West Coast by European settlers to California, but is found all over the world.

- Manila clams Venerupis philippinarum Taylor offers Manila clams year-round. The company’s two hatcheries enable breeding for sweet flavor, plump meats, a long shelf life and colorful shell patterns.

- Geoduck Panopea generosa The geoduck is the world’s largest burrowing clam and one of the most sought after sashimi ingredients. This native Pacific Northwest shellfish is sweet with two unique textures in the siphon and the mantel.

And it’s not that hard to believe if you see the company campus in Shelton.

The Taylor offices have been operating out of an old family home for about the last 40 years. Behind the home office are the two main processing facilities flanked by trucks ready to haul away fresh product for delivery. The oyster house sends product whole and raw, frozen in sheets of half-shells or shucked in containers.

Behind that facility, you’ll find vast mounds of oyster shell. Down the road a ways, you could get lost in their stores of geoduck tubes. It’s like a visit to the transfer station, only far more delicious and deliberate. As haphazard as these acres of mounds may sound, it’s all clean and organized and declares its own sense of purpose. This is the future of Taylor Shellfish — ready and waiting.

“If an opportunity lands in our lap, we’re not afraid to try it,” says Gonzalez.

Over the last hundred years or so, the family has acquired operations, by sale or lease, of around 12,000 acres in Washington state.

“Washington’s the only state that allows ownership of tidelands,” says Gonzalez. “We also lease from tideland owners. I don’t know the percentage that we’re actually using because we own a lot of unworkable tidelands.”

Why own unworkable land? Because it’s still vital to the resource. The more you own, the better a steward you can be for the environment on which your business relies.

“There are different things we need to farm around to keep the tideland intact,” says Gonzalez. “You also don’t want to overfarm the land, so we leave some intact.”

And sometimes you get the odd lucky strike. Tidelands that once were considered too muddy to plant turned out to be perfect for the company’s foray into the much-heralded shigoku oyster from Japan, grown in bags rather than loose on the flats or on longlines.

“We started growing tide-tumbled shigoku oysters on shellfish ground that had been unusable,” Gonzalez says.

Diversification and a deep understanding of their markets allow Taylor to cater to specific tastes.

“The Chinese market is shellfish hungry,” says Gonzalez. “The nice thing is that they prefer a larger oyster than the United States. In the United States the small- to medium-size oyster is the sweet spot, whereas they see those oysters as skinny or too small.”

No matter what size the oyster is, there’s someone who will pay a premium for quality.

“The Chinese market would purchase all of our product if we decided to allow that. It’s a great problem to have,” says Gonzalez. “One thing we’ve never had as a problem is selling our product.”

Now that Taylor manages its own seed production, boat fabrication, processing, delivery, restaurant sales and a slate of raw bars, there’s hardly an aspect of the business that’s not managed in house. What the family has really built is generations of job security, should they continue to be good stewards of the business and environment.

“I always tell my husband, ‘Well, we never have to look for a job again in our lives because we’re lifers at this point,’” says Gonzalez.

As of September, Oyster Bill is retiring. “I’ve done what I need to do, I think,” says Whitbeck.

Though he will leave behind the day-to-day work with a family and business he has watched grow over the last 15 years, “I’m not going to disappear,” he adds. “I’ve made some amazing friends.”

“We love the business,” Gonzalez adds. “We love that feeling of family here.”